By Erik Cordes, Chief Scientist, Associate Professor, Temple University

September 5, 2018

Team DEEP SEARCH poses for a photo on the bow of the R/V Atlantis as the ship made its way back to Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Image courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2018 - BOEM, USGS, NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 5.1 MB).

Although it was relatively short, this was an incredibly successful research expedition. We learned a lot about the different habitats in the study area between Virginia and Georgia. The R/V Atlantis mapped large areas of the ocean floor and helped us sample the waters of the Gulf Stream and Atlantic Ocean. We completed 11 dives in the human occupied vehicle (HOV) Alvin in the turbid parts of canyons, stunning cliff faces, bubbling gas seeps, and massive deep-sea coral reefs. The information we have gathered will help us to understand these habitats and their dynamics—methane flux into the ocean and atmosphere, the life spans of corals, the flow of carbon and nutrients through canyons, and much more. It will also help us to interpret the maps that we and others have made of the region and determine where other features may lay, still undiscovered. The ultimate goal of DEEP SEARCH is to provide all of this information to the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management as they consider opening up the areas offshore of the eastern U.S. to energy development, and as they develop management plans to deal with the potential impacts.

The biggest outcome of the cruise, in my mind, is the discovery of 85 miles of deep-sea coral reef that was previously unknown. The first inkling that this reef might be there came from the mapping efforts of the Okeanos Explorer earlier in the year, which was part of our larger DEEP SEARCH research program. These maps revealed a series of mounds and ridges in an area that was previously thought to be a relatively featureless part of the edge of the continental shelf. The high resolution of the multibeam echosounder sonar on the Okeanos allowed us to see these mounds and ridges for the first time. On the follow-up Okeanos cruise with the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Deep Discoverer, with DEEP SEARCH principal investigator Cheryl Morrison from the U.S. Geological Survey as the biology lead, one of the long ridges was first explored. Before the dive, this target was thought to be a long, rocky ridge based on our previous knowledge of the geology and biology of the region. However, when the ROV reached the seafloor, there was coral skeleton as far as the eye could see, throughout the entire dive. But this was only our first hint, a few short hours of observation, of what may be waiting for us in the area.

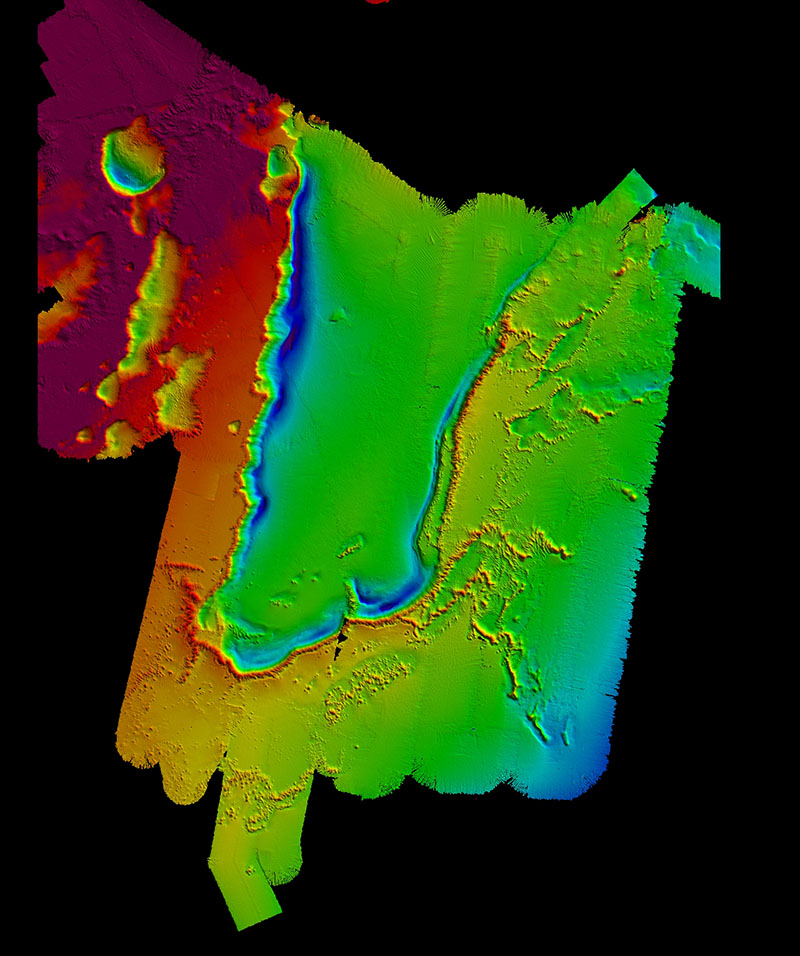

Map of the newly discovered reef complex off the coast of South Carolina. The linear reefs can be seen on the right of the image as a series of mounds and ridges in red and yellow against the green and blue background. Depths are shown by color, and range from approximately 900 meters (blue) to 700 meters (red). The total length of all of the linear features is approximately 85 miles. The total length of all of the linear features is approximately 85 miles. Bathymetry data collected by NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer Windows to the Deep 2018 expedition and R/V Atlantis AT-41, and map created by Meme Lobecker and Jason Chaytor. Image courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2018 - BOEM, USGS, NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

When preparing for our return trip to the area, we identified this site as a high priority for our work. The mound-like features north of the Okeanos dive location were intriguing and reminded us of the mounds formed by cold-water corals further inshore in this region and in other areas of the world. But the linear forms of the mounds were something that we had not seen before. We wondered whether these could, in fact, all be made of coral. I made the first dive with Cathy McFadden and Alvin pilot Bruce Strickrott, and the second dive was piloted by Jefferson Grau with Sandra Brooke and Kaitlin Kovacs. We were all surprised to find that these mounds were made by Lophelia pertusa, along with some other deep-sea corals, and that they were thriving in these conditions—further offshore and deeper than we had ever seen them before.

It has been known since the 1960s that there were deep-sea corals in the area, and there are many coral mounds closer to shore. A lot of the research dates back to the 1980s and 1990s with the work-horse Johnson Sea-Link submersibles that used to be run out of Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute in Florida. Pioneering research about the deep sea and corals in general came out of those expeditions. Personally, I have been studying deep-sea corals for over 20 years, but this is my first trip to the Atlantic Lophelia reefs. But many of the people on our DEEP SEARCH team have worked in these areas for decades. We are not ignorant of what has come before us; rather our collective body of experience makes this discovery even more profound.

On the third dive of the expedition, the DEEP SEARCH team discovered thriving Lophelia pertusa reefs in a region further offshore and in deeper water than other known Lophelia reefs in the U.S. Atlantic. Image courtesy of Dan Fornari, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Download larger version (jpg, 4.3 MB).

We were fortunate to have a reporter with us at sea to document this expedition, and we were all thrilled to see this discovery draw public attention to the presence of deep-sea corals throughout the world. It was difficult to show people back on land how different these reefs were, and there were many who saw this as a continuation of the coral habitats that have long been known from the area. Until our scientific findings are published in a peer-reviewed journal, the jury will still be out. But I can say that those of us on board, and the scientists that I have corresponded with directly while we have been out here, were surprised by the thriving reefs in this location. In fact, our models and those that have been independently developed by the NOAA Deep Sea Coral Research and Technology Program predicted this area to be moderate to low quality habitat for reef-forming corals. Because it was such a remote possibility that there would be reefs in this area, they were not included in a nearby special protected area for deepwater corals that was recently established by the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council.

I hope that we can all celebrate the positive stories coming out of this research and use it to help lift up the scientific research of others. Good news is too rare these days, and this is a victory that we can all share. We have found a pristine coral reef in our own backyard, not far off the coast of South Carolina. It took many years to build up the knowledge that led us here, the vision of many government agencies to put the DEEP SEARCH project together, and some sheer good luck to be diving in the right place on the right day. The general public is largely unaware that deep-sea corals even exist. It is my hope that the discovery of this novel coral habitat can help raise the profile of deep-sea coral research everywhere and make the protection of this public resource a high priority.