By Zach Proux, College of Charleston

August 30, 2018

Watch as the DEEP SEARCH team climbs over 500 vertical meters of rock wall within Pamlico Canyon. Video courtesy of Dan Fornari, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Download larger version (mp4, 76 MB).

When I was little, my dad and brother used to call me “Rocket Man,” a nickname I hated with a passion. If you’re familiar with the 1997 film starring Harland Williams, you may remember the scene in which “Rocket Man” sneezes particularly aggressively into his helmet while in space...it was for this scene and my unfortunately aggressive sneezes that I earned this nickname. I focused on the negative aspects of the nickname when I should have focused on the positive. Rocket Man was an explorer. A clumsy explorer, but an explorer nonetheless. Sitting here today, I think that nickname was more appropriate than even my dad or brother realized.

As the DEEP SEARCH expedition aboard the R/V Atlantis winds down, I’ve been asked to write about my first experience diving in the human occupied vehicle Alvin. Only 24 hours after the fact, I’m surprised to say I don’t know where to begin. Those who know me know me know I’m not often left speechless...but there’s a strange haze that comes after ascending from 1,600 meters deep in a submarine canyon. Going from dense fields of bioluminescent zooplankton within arm's reach to processing samples until 6 in the morning leaves you a little discombobulated.

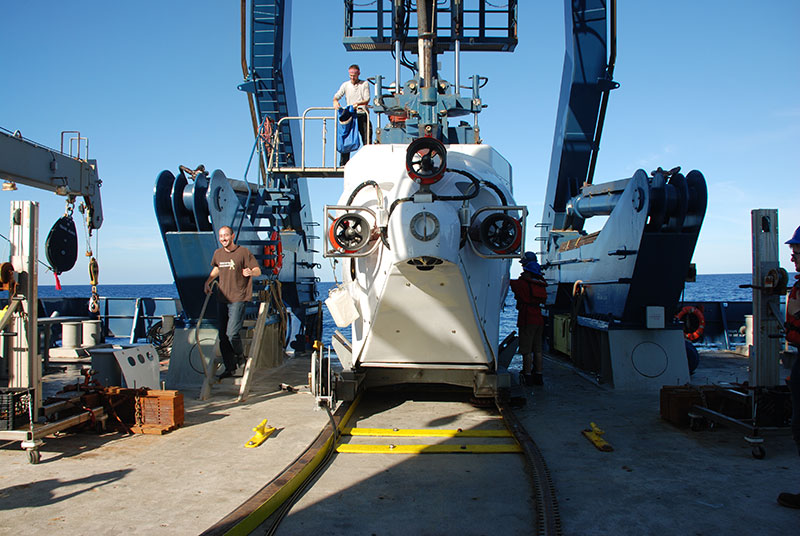

College of Charleston master’s student Zach Proux is all smiles as he exits the Alvin after his first dive. Image courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2018 - BOEM, USGS, NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 5 MB).

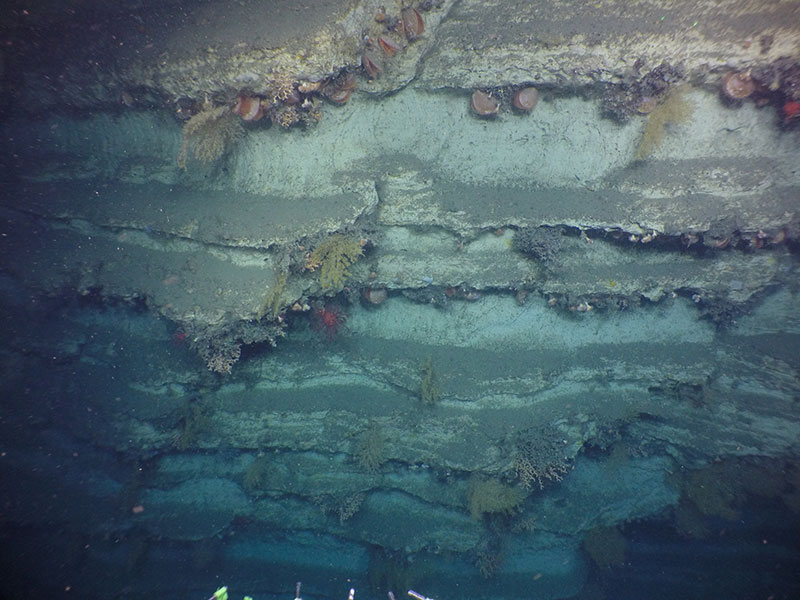

On bottom in Pamlico Canyon, we saw an incredible diversity of fish – mostly with dark grey coloration; sea stars with their mouths facing upwards and their arms splayed out in the water column like a wildflower’s petals; and a pycnogonid, more commonly known as a sea spider, nearly 20 centimeters across. Of more interest to our scientific goals, there were the hundreds of ~100-120-centimeter coral colonies living on 100-meter sheer walls; differential erosion over millennia had created massive bookshelf-like walls and ledges. Manganese iron oxide provided a sort of banded black lacquer, like the stripes on a prison jumpsuit. In total, with Alvin pilot Jefferson Grau flying and lead scientist Jason Chaytor directing, we climbed 550 vertical meters in this strange undersea world, saw some amazing things, and collected some valuable data.

Alvin explored Pamlico Canyon off the coast of North Carolina and observed stunning rock walls covered in a diversity of corals. Image copyright Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2018 – BOEM, USGS, NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 4.3 MB).

As a spatial ecology research assistant in NOAA’s Deep Coral Ecology Lab (DCEL), my daily life includes a lot of computer work. I live and work in Charleston, South Carolina, under the direction of my primary adviser at College of Charleston, Dr. Leslie Sautter, and the man that gave me this opportunity – Dr. Peter Etnoyer. Dr. Etnoyer leads NOAA’s Southeast Deep Coral Initiative (SEDCI), a four-year multidisciplinary effort (2016-2019) designed to support regional management efforts through science and exploration of the deep-sea. SEDCI is sponsored by NOAA’s Deep Sea Coral Research and Technology Program (DSCRTP), whose mission it is to identify and catalog occurrences of deep-sea coral all over the world. There’s a really cool interactive map that shows all the published records of deep-sea coral right now.

The points on that map are generated from deep-sea dives just like the one I did yesterday. In the coming months, I will annotate the still images from DSV Alvin’s dives for presence or absence of coral and what type of substrate there is. These data inform mathematical models that allow us to predict which areas of the seafloor are most likely to have deep-sea coral. I won’t get into the weeds on that stuff, but this is the larger context of my presence on this expedition – so you don’t think scientists are just out here joy-riding in a submarine. Although, there was plenty of joy involved.

Zach spent much of this expedition helping run the tag lines for the CTD, and so it was only fitting that his ice bath involve at least one Niskin bottle. Image courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2018 – BOEM, USGS, NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 5.1 MB).