By Caitlin Adams, Web Coordinator, NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

August 28, 2018

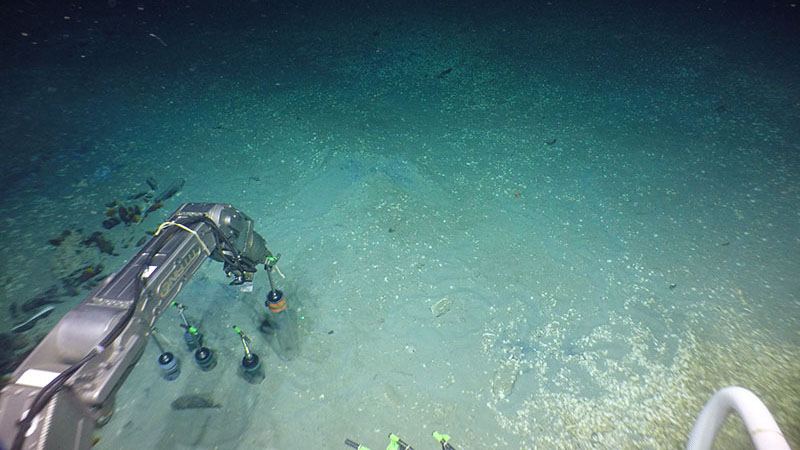

Each time that we’ve sent Alvin to the seafloor so far during this DEEP SEARCH mission, we’ve sent some number of pushcores down with it. Pushcores are sampling tools designed to bring intact columns of sediment to the surface. They’re simple devices, really: a clear plastic tube with an open base and a capped T-handle top that lets the Alvin pilot easily lift the pushcore, plunge it into the seafloor, and then quickly lift it back into the sampling basket, where it is securely stored in a larger PVC tube that has a built-in rubber stopper so that the core is sealed until it reaches the surface.

Alvin takes a set of pushcores on the seafloor at Blake Ridge seep. Image copyright Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2018 - BOEM, USGS, NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 4.3 MB).

Though the devices themselves might be simple, there’s actually a lot of complex information to be learned from the surface sediments we collect. Both Amanda Demopoulos’ and Mandy Joye’s labs are focused on understanding the ocean better through this “mud,” as it’s often affectionately called. They approach it from different perspectives, though: Amanda is a benthic ecologist, meaning she’s largely focused on the tiny creatures living in the mud, while Mandy is a biogeochemist who studies the chemical and microbial processes that shape the environments those creatures live in.

Because they’re interested in such different research questions, the methods they employ to process the cores also differ—but in both cases these are lengthy processes that have kept both mud teams pulling some of the longest hours of this expedition. When the cores first arrive on deck, they must be immediately transferred to the cold room to best preserve their fresh-from-the-seafloor condition. There, members of each team work together to visually assess the core—how deep is it? What color is it? How does it smell? The questions might sound basic, but the answers are important: each lab samples a different depth profile, color indicates sediment type and smell will quickly tell you if there’s methane or sulfide present. Based on these assessments, the two labs split up the day’s haul and get to work.

Amanda Demopoulos and Jason Chaytor section a sediment core for preservation and future analysis. Image courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2018 - BOEM, USGS, NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 4.4 MB).

For the Demopoulos team, that means emerging from the cold room to section the top 10 centimeters of each core into three separate fractions. The mud is washed and transferred into individual Nalgene bottles, and all samples will be preserved and brought back to the United States Geological Survey Wetland and Aquatic Research Center in Gainesville, Florida. There, the mud will be sieved to reveal a diversity of microscopic creatures. They’ll identify all of the different animals in each sample, and they’ll also do chemical analyses on those animals to better understand how they connect to the larger fauna of the midwater—giving us a better understanding of the food webs in these deep-sea communities.

Mandy Joye inspects a sediment core before processing begins. Image courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2018 - BOEM, USGS, NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 4.7 MB).

For the Joye lab, onboard processing is a bit more complex: because they are interested in sensitive chemical processes, sampling conditions must be more closely regulated. They’ll stay in the cold room as they section each core and prepare sampling bottles for analyses both elsewhere on the ship and back at their lab at the University of Georgia. For each sample that’s collected, they do anywhere from 15 to 20 different analyses—Joye estimates they’ll walk off the ship next week with nearly 2,000 samples in tow! All of those analyses will help the DEEP SEARCH team to better understand the biogeochemical environments of our focal habitats (corals, canyons, and cold seeps) and will shed light on the connectivity of these ecosystems along the U.S. Atlantic continental margin.

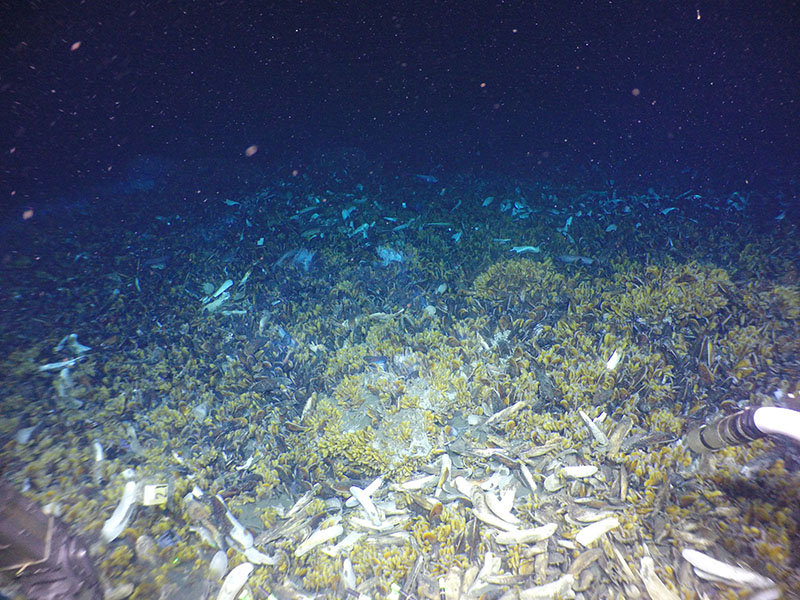

Today’s dive was likely the peak workload for both teams, after the initial frenzy of our Pea Island dive. We explored Blake Ridge, a known seep environment filled with abundant chemosynthetic mussel communities. The onboard team, Mandy Joye, reporter Chris D’Angelo, and pilot Jefferson Grau, collected a whopping 33 pushcores throughout their dive. It took a few hours just to visually inspect all 33 cores, and it took an all-nighter for both teams to get through processing their half of the cores. The saving grace of an Alvin cruise, though: you can always catch a few hours of rest before the next day’s dive surfaces!

An example of the abundant mussel beds seen at Blake Ridge seep. Image copyright Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2018 - BOEM, USGS, NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 5.3 MB).