By Caitlin Adams, Web Coordinator, NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

August 26, 2018

When I first started planning this expedition with the DEEP SEARCH team nearly a year ago, I had no idea that it would result in such a spectacular expedition filled with successful dives, consistently great weather, and exciting discoveries. But what was most personally surprising and awe inspiring for me was that I, too, got the chance to go down to the seafloor in Alvin .

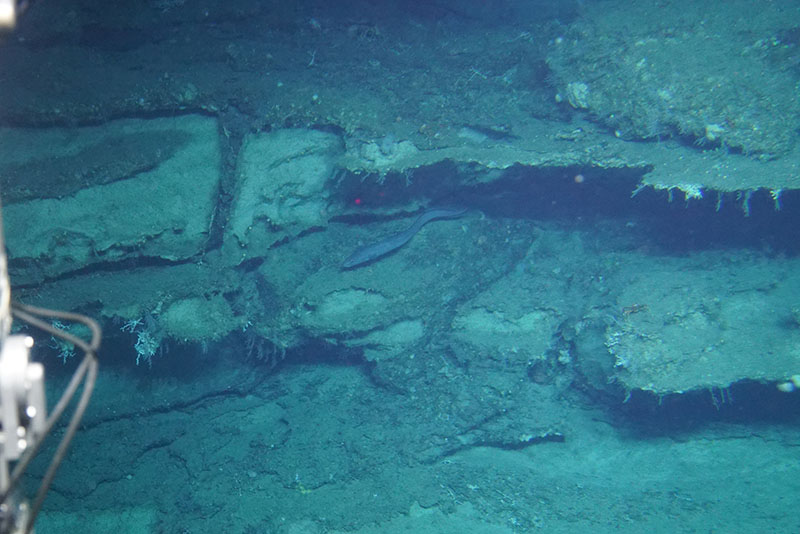

A conger eel swims along a ledge at Stetson Banks. Image copyright Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Download larger version (jpg, 6 MB).

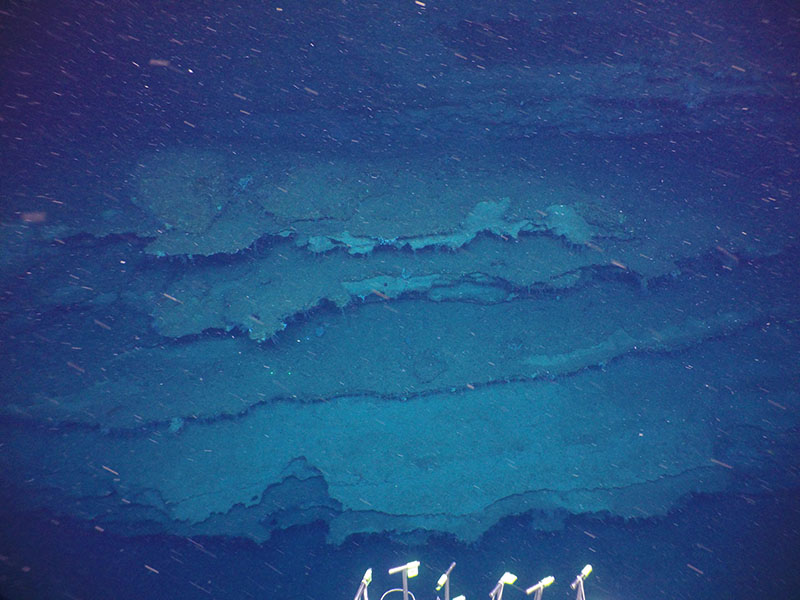

Most of the ledges and rocky outcroppings we saw had corals, like these plexaurids, lining their edges. Image copyright Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Download larger version (jpg, 7.5 MB).

For the first week of the cruise, I looked on each morning as pairs of scientists boarded the sub; and again each afternoon as we all cheered for their arrival back on deck. Seeing what they brought with them from the seafloor each day was already the most exciting aspect of deep-sea exploration that I’ve experienced so far in my career. This expedition is the first time I have ever seen deep-ocean creatures in person. I’ve learned about them, I’ve seen all of the Okeanos Explorer’s beautiful images of them, and I’ve planned expeditions to go find them—but I still hadn’t realized how special it would feel to see my first biobox full of live Lophelia unloaded from Alvin’s sampling basket. And I definitely hadn’t even begun to realize how special it could feel to see that Lophelia growing on the seafloor mere feet from where I sat (in a fully pressurized titanium submersible!).

On the morning of August 26, I got my chance to begin realizing how special that experience is—and I say “begin” even now, three days after the fact, because it still feels remarkably surreal. I’ll be forever grateful to Erik Cordes for the opportunity. As chief scientist, he is in the challenging position of assigning dive slots each day; with a limited number of dives and a large science team, there were never going to be enough slots for everyone on this cruise. However, Erik made it clear from the start that he would do his best to prioritize those who have not experienced a submersible dive before (be it in Alvin or the former Johnson-Sea-Link submersibles). Almost every day, Alvin has carried someone to the seafloor for the very first time—and we have an amazing collection of celebration photos to show for it!

In a small space like the Alvin sphere, group selfies become a bit more challenging. Here, Amanda Demopoulos, Jefferson Grau, and Caitlin Adams almost succeeded with their framing... Image copyright Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Download larger version (jpg, 5.1 MB).

A wide view of the ledge features we observed throughout our dive at Stetson Banks. Image copyright Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Download larger version (jpg, 4.5 MB).

After waking up extra early and excitedly getting ready, I spent about half an hour on the back deck looking on with the usual crowd of scientists as the Alvin team readied the sub. When the “All aboard!” was called though, I got do something very different than every other morning so far: I climbed the A-Frame stairs, slid over the intimidatingly tall hatch wall, and boarded the sub with Amanda Demopoulos and pilot Jefferson Grau for a speedy descent to the bottom. With a maximum depth of 558 meters at our site, Stetson Banks Shallow, it felt like we were on the seafloor in no time at all—and in fact it did take just 17 minutes to descend.

The inside of Alvin, or the “sphere” as it’s often called, is cozy but not too tight. The pilot sits on a short stool in the center and has a viewport directly in front of the sub, allowing him to both fly the sub and use Alvin’s manipulator arms to collect samples and place them in the sampling basket at the front of the sub. Amanda sat in what’s called the port observer seat on the left side of the sphere; her two viewports let her look both to the front and bottom. The manipulator arm that does most of the sampling is also on the port side, so the more senior scientist usually sits on that side to be able to best advise the pilot on what samples are needed.

Experience the entire eight-hour dive in just over three minutes with this time-lapse video. Video courtesy of Dan Fornari, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Download larger version (mp4, 244.4 MB).

Finally, I sat in the starboard observer seat, the spot most often occupied by first-time Alvin divers. Just because I was new though did not mean I was without responsibility: both scientists on each dive keep a running log of the dive to note any observations/activities as well as their time and depth, and each has control of the video cameras on their side of the sub. Alvin is outfitted with two cameras on each side, one at the top of the sub and one closer to the level of the sampling basket. When we were transiting, I made sure that my camera was recording a wide view of the dive, but when we were sampling, I would train my cameras on the manipulator arm, ensuring that we had good imagery of the corals we were collecting and the bioboxes or quivers that they were secured in.

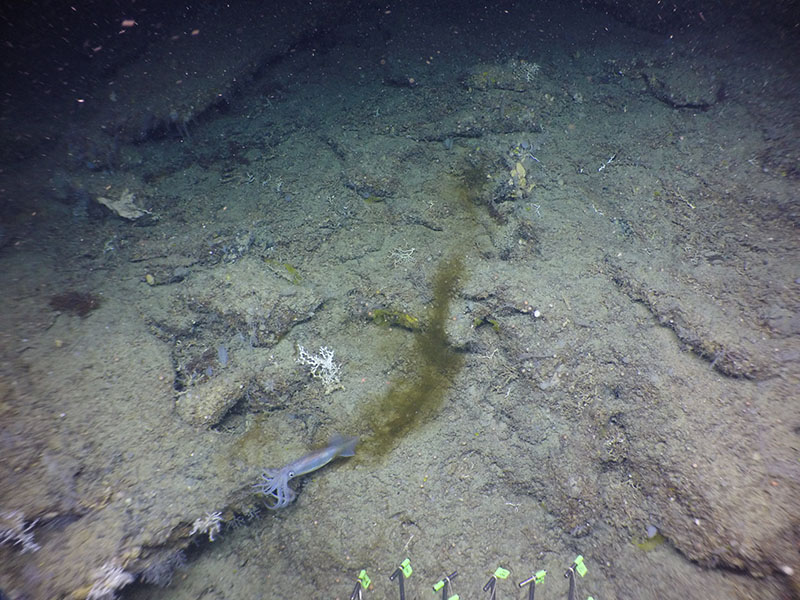

Squid are often attracted to the vibration of the Alvin, and we almost always had at least one squid swimming and inking in our vicinity. Image copyright Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Download larger version (jpg, 4.8 MB).

What we saw that day was nothing short of amazing: from the moment we landed on the seafloor until we surfaced, we were seeing deep-sea corals. We spent most of our dive climbing up a 130-meter high wall; though we knew the wall was there from existing mapping data, we were not expecting it to have as many rocky outcroppings and ledges as it did. On most of these features, there were corals growing at the edges, getting their food from the abundant marine snow in the passing currents. We saw lots of crabs, fish, and eels on these ledges too, and it seemed that no matter where we were in the dive, a minimum of one curious squid was circling the vehicle. Most of the corals we saw were relatively short, their growth likely controlled by the strong currents in the region. Even so, their diversity and abundance was incredible to me. To be among the first people to witness such a unique environment, and to know that the samples we collected that day will help the DEEP SEARCH team characterize it even further beyond our observations, is truly an experience I will never forget.

Each time that someone dives in Alvin for the first time, her return to the surface is celebrated with an ice bath and handcrafted costumes. Image copyright Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Download larger version (jpg, 3 MB).