Video highlights from exploration of the shipwrecks. Video courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download (mp4, 54.0 MB).

On this page: Loss of Ohio | Search for Choctaw | Choctaw History | 2017 Results | Future Research | Additional Images | Mission Specs

On May 23, 2017, researchers from NOAA’s Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary, NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Lab, and the University of Delaware discovered two shipwrecks during the second phase of the exploratory research project funded by NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration and Research [OER].

Choctaw’s rudder and propeller. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 241 KB).

While hovering over the bow of the Ohio, the ROV imaged both the capstan and pilot house. Just inside the left windows of the pilot house, the ship’s wheel is visible. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 211 KB).

Follow-up investigations of these sites carried out between June and August of 2017 included the use of an autonomous underwater vehicle [AUV] from Michigan Technological University’s Great Lakes Research Center and a remotely operated vehicle [ROV] provided and piloted by Northwestern Michigan College. Based on the preliminary results, researchers believe the two sites are those of wooden steamer Ohio and steel-hulled steamer Choctaw. Both are historically and archaeologically significant sites.

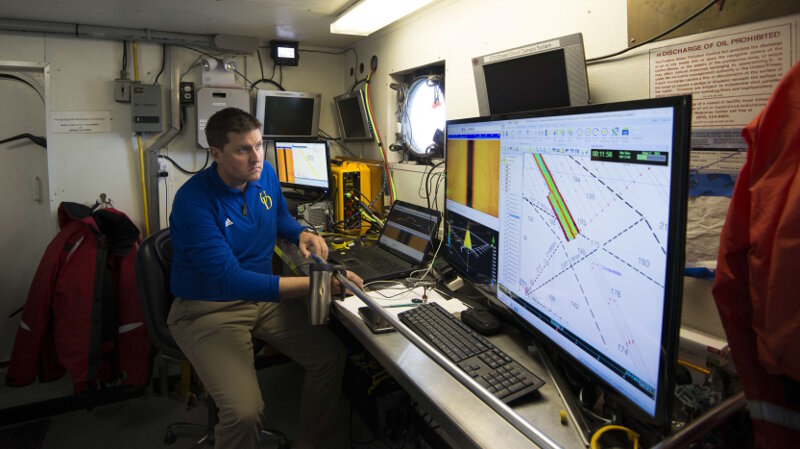

Dr. Guy Meadows (left) and Chris Pinnow (right) of Michigan Technological University (MTU) discuss sonar imagery with Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary Research Coordinator John Bright (center). The image shown on the computer screen is from the site believed to be Choctaw. Acoustic data was collected via an AUV operated by MTU during field operations in June, 2017. Image courtesy of Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary/NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 7.3 MB).

Ohio represents an early version of what later became the iconic Great Lakes bulk carrier design. In fact, Ohio represents some of the earliest attempts at Great Lakes-specific ship designs emerging after the introduction of steam propulsion as an alternative to sail power. Choctaw was also an innovation in ship construction, a derivative of the famous ‘whaleback’ Great Lakes vessel type.

Ongoing historical and archaeological investigations will undoubtedly bring to light details that generate more questions and opportunities for inquiry, research, and understanding of these incredibly preserved shipwrecks. Future research will not only assist the sanctuary in managing the sites, but will provide interpretive materials for public.

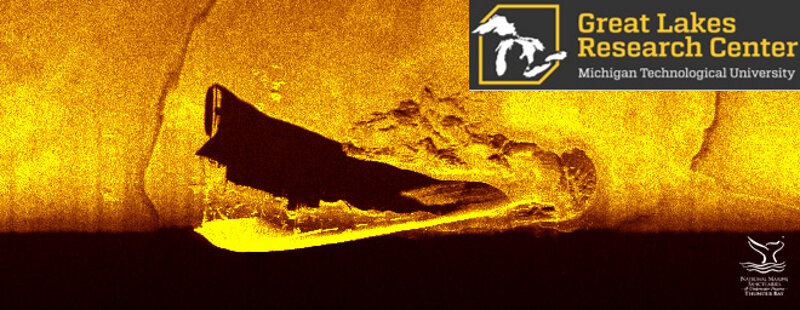

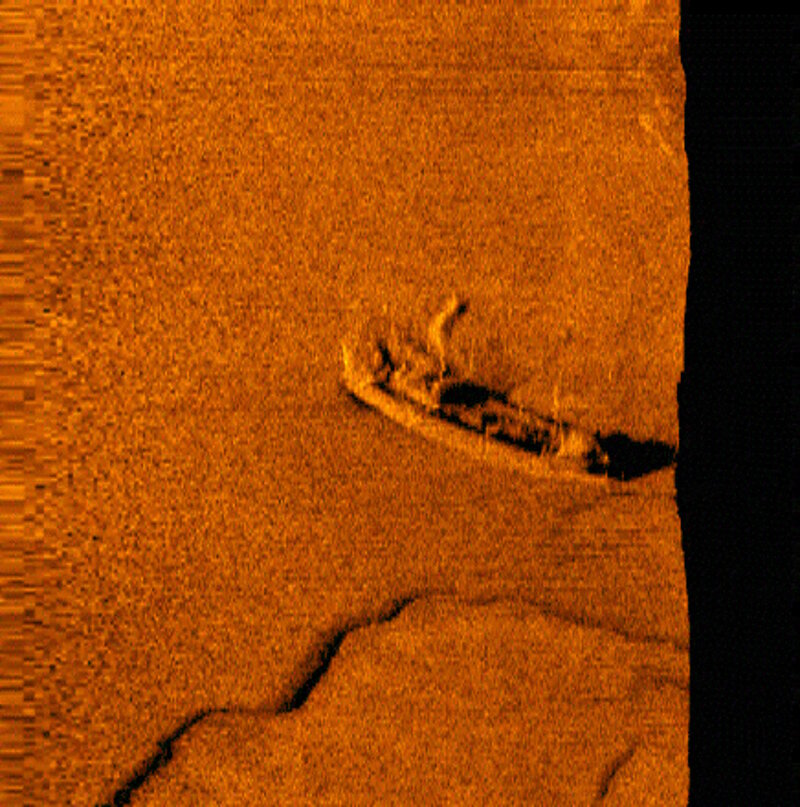

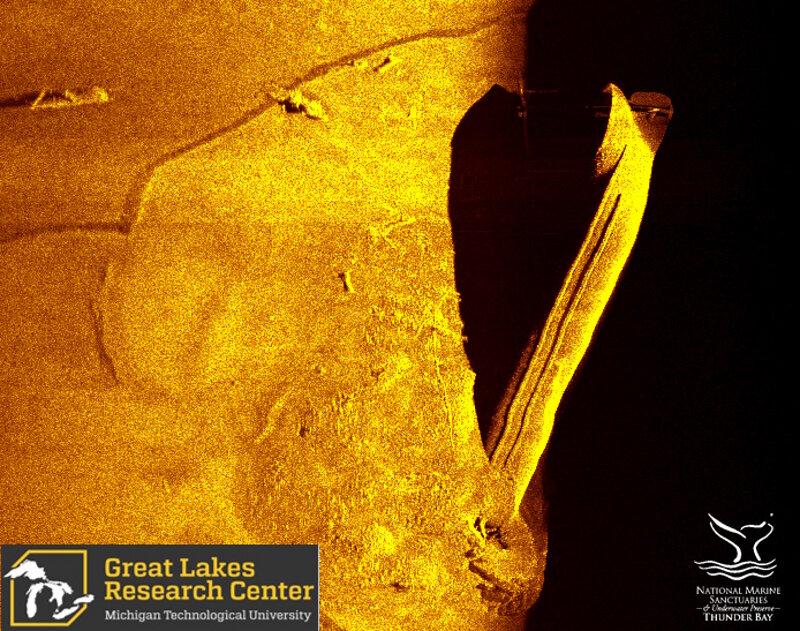

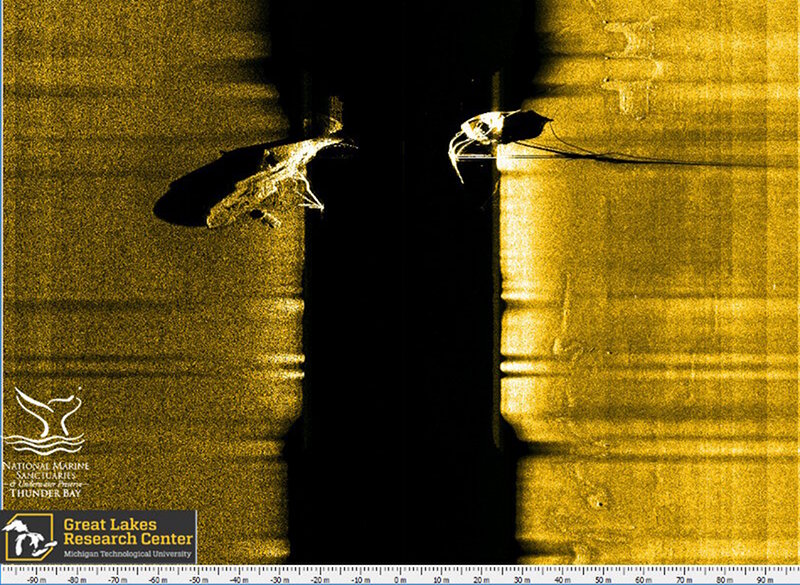

Sonar image of the site first classified as ‘Target 2’ in May, 2017. AUV-based scanning was conducted in June to produce this image. The vessel was nearly upside-down and partially buried in the bottom of Lake Huron. Acoustic shadows reveal a rudder, propeller, and the outline of the stern cabin structures. Image courtesy of Michigan Technological University/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download image (jpg, 93 KB).

A starboard-side profile of wooden bulk carrier Ohio. Here, early bulk carrier design is show via the small, forward pilot house, cargo holds midships with masts in place, followed by stern cabins and steam propulsion machinery. Many of these features were observed during AUV and ROV investigations, including the three masts, the pilot house along the bow, and a very similar shaped rudder and stern. Image courtesy of the Great Lakes Maritime Collection, Alpena County George N. Fletcher Public Library. Download larger version (jpg, 10.8 MB).

In September 1894, wooden bulk carrier Ohio departed Duluth, Minnesota, for Ogdensburg, New York, loaded with a cargo of grain. This transit required Ohio to cross Lake Superior, pass through the Soo Locks, then traverse Lake Huron, past Presque Isle and Thunder Bay. Along this route, Ohio encountered heavy weather and busy shipping lanes, a dangerous, yet all too common, combination.

Meanwhile, two schooners, Ironton and Moonlight, were being towed by steamer Kershaw. The three ships were heading north when they encountered Ohio in rough weather, 10 miles north of Presque Isle. It was during this critical moment, with the vessels about to pass each other, that Ironton’s towline parted. The schooner broke free, veered off course and collided with Ohio. Both vessels sank in half an hour. Sixteen crewmembers of Ohio got into lifeboats and were later picked up by schooner Moonlight. The First Mate was picked up by Kershaw after clinging to a floating ladder for nearly two hours. Another steamer passing nearby, the Hepard, picked up two of Ironton’s crew while five of them, including Captain Peter Girard, perished in the accident on 26 September, 1894.

The stern of the wooden bulk carrier thought to be Ohio; this was the first feature seen during ROV operations in August, 2017. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 233 KB).

Ohio was an early version of the wooden bulk carrier, built in 1873 by J. F. Squires of Huron, Ohio. It measured 202 feet in length, 35 feet in beam, and registered 1,101 gross tons. By this part of the 19th century, bulk carriers represented industrialization of the maritime trades where large ships carried bulk commodities at lower cost.

Owned by C. W. Elphicke of Chicago, Ohio carried 1,000 tons of flour, equal to 10,000 barrels, when lost. The wooden schooner Ironton was built by George Notter at Buffalo in 1873. Ironton was 190.9 feet in length with a 35.4 foot beam, and registered 785 gross tons. The Ironton has not yet been found and was not located during the 2017 exploratory survey efforts.

In 2008, researchers from Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary partnered with diver and historian Stan Stock to map the remains of schooner Kyle Spangler, located by Stock while pursuing his own efforts to locate ‘straight back’ steamer Choctaw, a unique type of Great Lakes freighter derived from the iconic ‘whaleback’ design. The archaeological maps created for Kyle Spangler led to it being listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

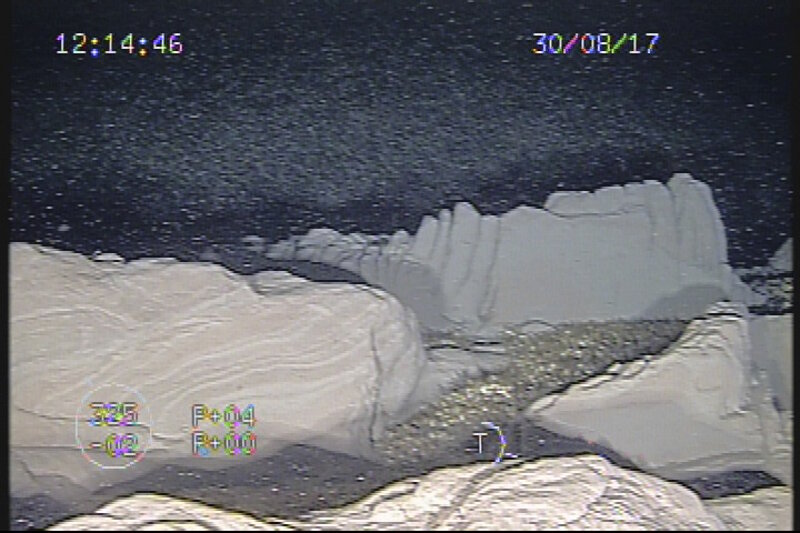

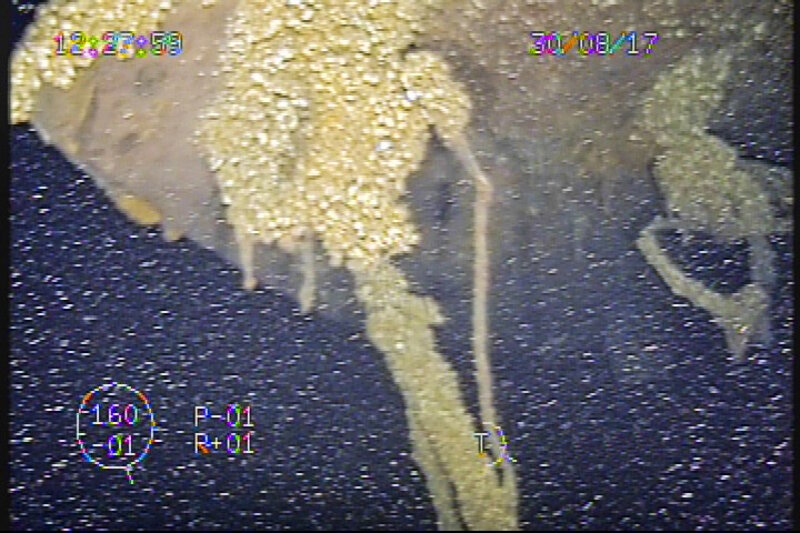

As the ROV touched bottom for the first time, large clay formations were observed. This is the material that covers the bow section of Choctaw which is buried and not visible. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 233 KB).

Based on the success of this collaboration, sanctuary researchers and Stock joined efforts to try and locate Choctaw. Partnering with the University of Rhode Island in August 2008, Thunder Bay renewed survey efforts off Presque Isle and Rogers City. The team succeeded in locating remains of another vessel, Messenger, but did not find their intended target.

Continuing upon this search for Choctaw, the Sony Corporation supported a 2011 exploration effort called Project Shiphunt. During this project five high school students from Saginaw, Michigan, worked with NOAA archaeologists and researchers from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute to explore deep waters off Presque Isle, Michigan. During the course of their survey they located two new shipwrecks, the schooner M.F. Merrick and bulk carrier Etruria. The Choctaw, however, remained elusive.

The undiscovered ship remained a research objective of the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary; not only was the vessel of a unique design, its history embodied many of the challenges of maritime commerce on the Great Lakes. Much like Kyle Spangler and numerous other shipwrecks within the sanctuary, Choctaw’s remains likely meet several of the eligibility requirements for the National Register of Historic Places, a testament to the vessel’s considerable historical and archaeological significance.

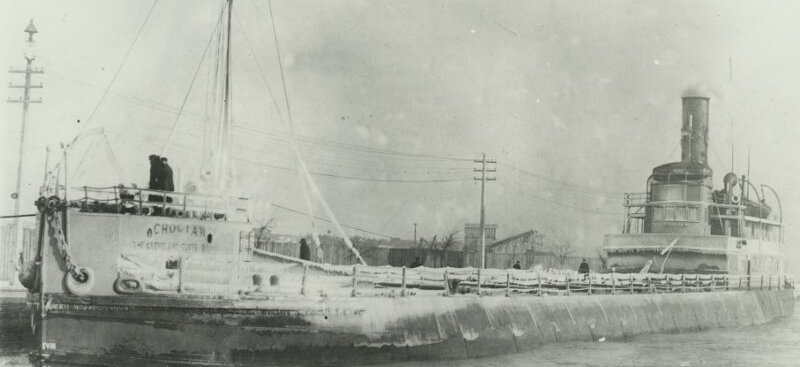

View from the port bow of Choctaw, shown here dockside amid cold weather. Ice has formed along the rigging and deck, though its characteristic ‘monitor’ style design is clearly seen with the small cabin over the bow and rounded sides defining the area surrounding the cargo hatches; date unknown. Image courtesy of Great Lakes Maritime Collection, Alpena County George N. Fletcher Public Library. Download larger version (jpg, 21.0 MB).

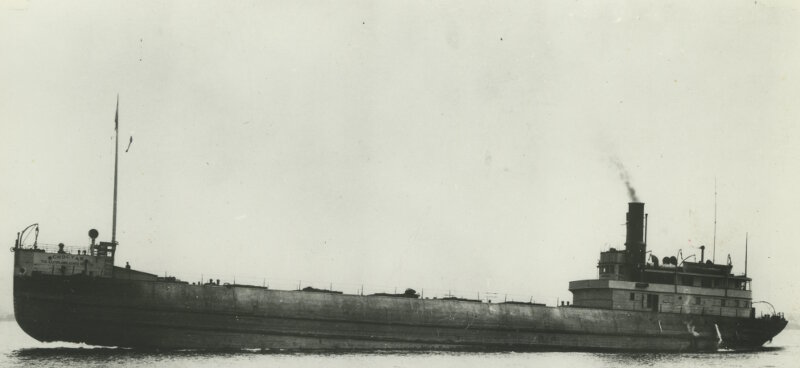

Another port-side view of Choctaw traveling light with much of its hull out of the water. Here, several features observed during the ROV missions in August, 2017, were corroborated. These include the stern cabin layout; locations of windows and doors; locations of bits, capstans, and davit arms; the location of the funnel and funnel cape; and the hatches moving forward of the stern cabin. Image courtesy of Great Lakes Maritime Collection, Alpena County George N. Fletcher Public Library. Download larger version (jpg, 16.8 MB).

At the close of the Civil War, iron and steel ships began to dominate the shipbuilding trade, ultimately replacing the traditional wooden hulls of America’s merchant fleets. The ship-building city of Cleveland, Ohio, with abundant coal, iron, and capital, naturally turned to steel and the innovative vessel designs it made possible. Soon, shipyards were producing larger and more efficient cargo carriers. The straight back or “monitor” design, a direct descendent of the iconic whaleback design, appeared in 1892.

This design, produced by the Cleveland Ship Building Company, had a conventional bow, but the ship’s metal sides slanted outward from the main deck to the waterline at almost a 45 degree angle. The hull resembled later submarines. All cabins were located at the stern, and the smoke stack was straight up and down. The "monitor" never fully developed as a ship class and only three were built: Andaste, Choctaw, and Yuma. Choctaw was 266.9 feet in length, with a beam of 38.1 feet and a 17.9 foot depth of hold. The ship registered 1,573 gross tons, with a capacity of 3,050 tons. It was powered by a 900-horsepower triple expansion engine and two Scotch boilers.

Like many Great Lakes ships, Choctaw was not immune to mishaps. In April 1893, an engine explosion killed two crew members. The vessel sank at Sault Ste. Marie in a collision with the steamer Waldo in May 1896. A few years later, in May 1900, Choctaw grounded near Point au Pins, and in April 1902, Choctaw struck a rock at Marquette and partly sank after getting inside the harbor.

The ship’s fatal blow came on July 12, 1915 off Presque Isle. Up-bound in a dense fog with a cargo of coal, Choctaw was hit between No. 1 and No. 2 hatches by Canadian Steamship Company freighter Wahcondah. Although the ship sank in only seven minutes, Captain Charles A. Fox and his crew of 21 men were all rescued and taken aboard Wahcondah.

Dr. Art Trembanis of the University of Delaware oversees exploratory survey operations in May 2017. The university partnered with Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary to operate an EdgeTech 6205 Bathymetric Side Scan Sonar from NOAA vessel R8001 and completed nearly 100 square miles of acoustic scanning off Presque Isle, Michigan. During the course of this survey, two new shipwreck locations were identified and marked for further investigation throughout the summer of 2017. Image courtesy of Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary/NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 6.6 MB).

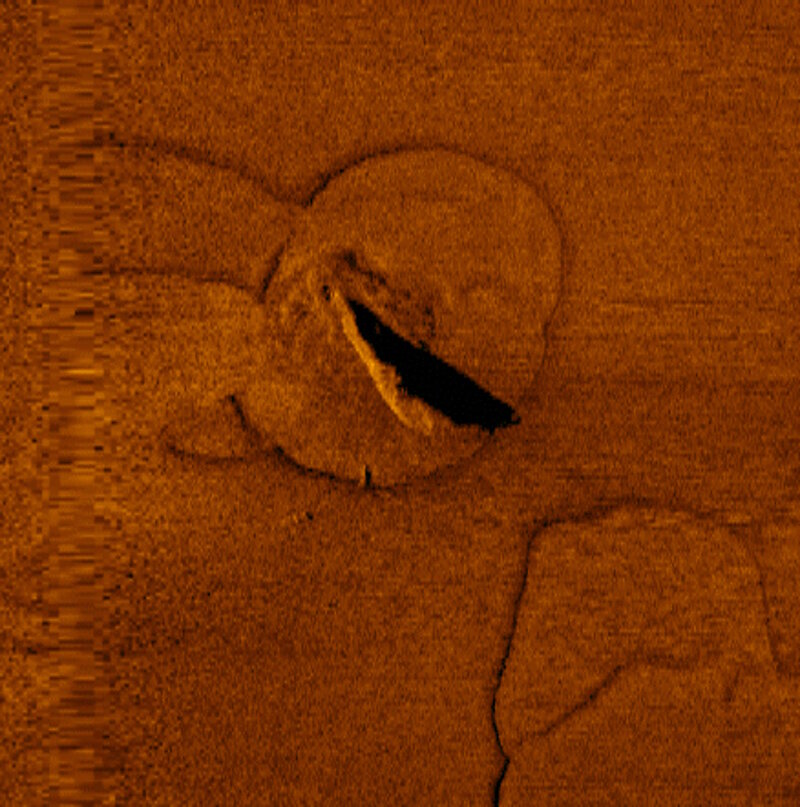

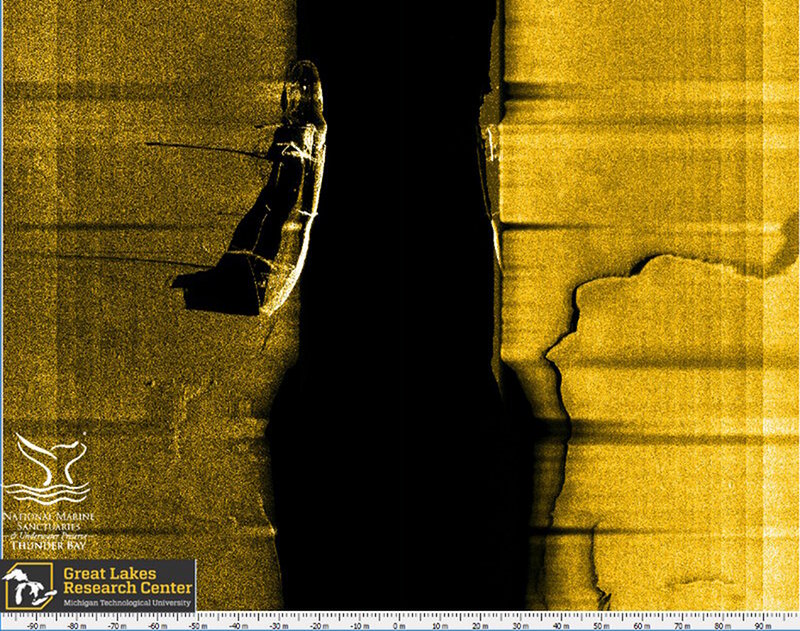

As part of a NOAA OER grant awarded to the sanctuary, researchers from the University of Delaware, NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Lab, and NOAA’s Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary conducted a large-scale, exploratory survey project near Presque Isle, Michigan. Expanding upon sanctuary-led surveys that occurred in 2008 and 2011, the team covered 94 square miles of unexplored lake bottom utilizing an EdgeTech 6205 phase measuring echosounder with combined bathymetry and side-scan sonar imagery. During the course of this field campaign, the team located two acoustic anomalies which appeared to be undiscovered shipwrecks; at the time they were designated ‘Target 1’ and ‘Target 2.’ It was Tuesday May 23, 2017, that these targets, now believed to be the remains of Ohio and Choctaw, were first seen by researchers.

A second pass of the vessel now believed to be Ohio. Researchers from the University of Delaware and Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary discovered a vessel at this location on 23 May, 2017. Image courtesy of the University of Delaware. Download image (jpg, 175 KB).

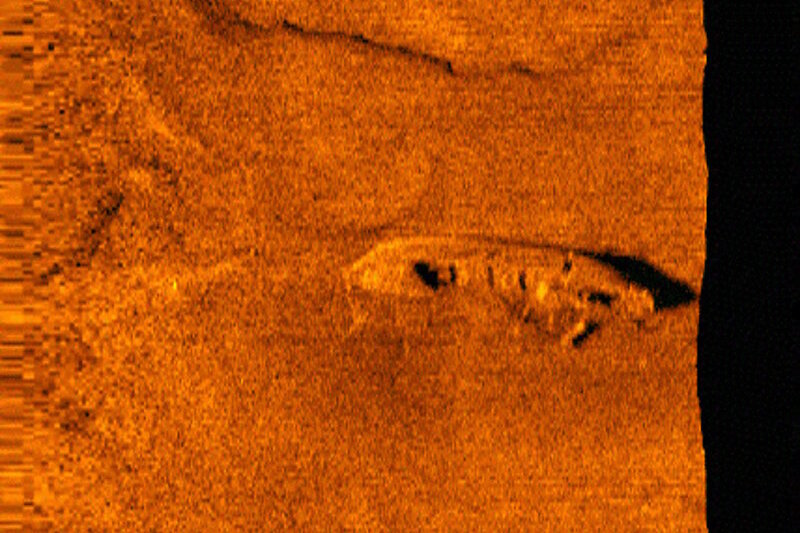

On the same day that the remains of Ohio were discovered, researchers also located the remains of what appeared to be straight back steamer Choctaw. Follow-up investigations of both sites took place from June to August, 2017. Image courtesy of the University of Delaware. Download image (jpg, 145 KB).

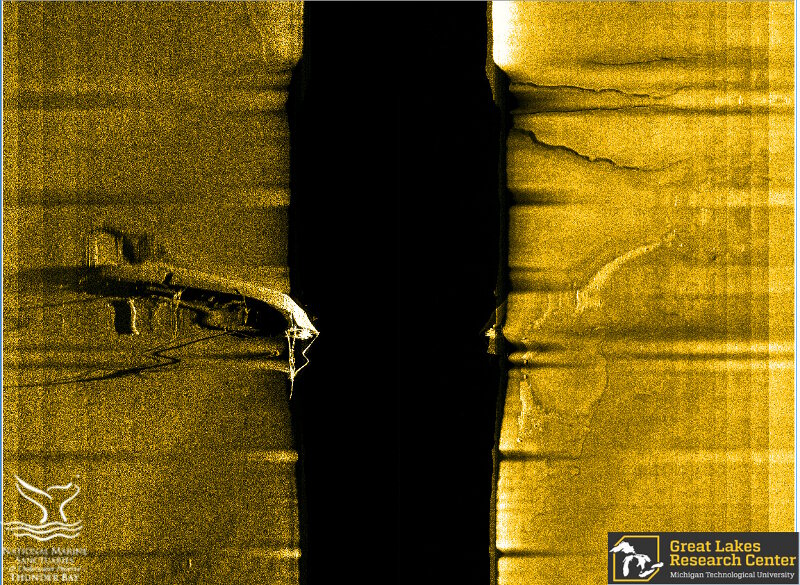

Dr. Art Trembanis’s team from the University of Delaware cataloged each site with their sonar instrumentation, and in June, the NOAA-led team returned with Dr. Guy Meadows from Michigan Technological University. Using a sonar-equipped AUV, the team surveyed each target in much greater detail. At ‘Target 1’ the apparent remains of a wooden bulk carrier, which historical records indicated was most likely Ohio, were visualized to show its pilot house, cargo hatches, stern structure, masts and rigging, and localized debris field.

Despite the abundance of details revealed at ‘Target 1’ the other shipwreck target—Target 2—proved difficult to characterize. As continued AUV surveys revealed, the vessel was upside down and partially buried in the lake floor. As a result, additional underwater data was needed. To this end, the sanctuary partnered with Northwestern Michigan College to use their ROV for further site investigation. In particular, information was needed from underneath ‘Target 2’ where the sonar could not scan. This was the area where diagnostic features would be observed.

Here, an AUV sonar scan runs parallel with the long axis of the vessel researchers believe is that of wooden bulk carrier Ohio. Two upright masts are easily seen fore and aft, while a third collapsed mast can be seen via its shadow amidships. Likewise, the acoustic shadow of the pilot house forward reveals a textbook bulk carrier design feature. Image courtesy of Michigan Technological University/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 2.0 MB).

An AUV-acoustic scan of the vessel identified as straight back steamer Choctaw collected in June, 2017. The rounded sides characteristic of this vessel can be seen via the lack of defined edge on the upper (left) side as it extends into the lake bottom. Its unique, pointed stern is also visible. Almost half of Choctaw, however, appears buried in the lake bottom. Image courtesy of Michigan Technological University/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 577 KB).

Visiting ‘Target 2’ first, the video recordings from the ROV mission were stunning. The vessel’s telltale straight back, or modified whaleback, design was evident. Dozens of features indicated in the builder’s plans were visible. The stern deck cabins, machinery, and tackle identically matched the historical records—engineering plans and photographs included. For the first time in over a century, the remains of Choctaw were finally seen by human eyes.

Following the visit to ‘Target 2,’ the ROV team visited ‘Target 1’ for additional documentation. Here again, several features were recorded that matched with historical information. In this case, historical images of Ohio showed great similarity with the newly discovered shipwreck site. Both had three masts, similar overall size and dimension, similar pilothouse features, and both were constructed with wood. At both sites, the information recorded during the sonar and ROV operations supported a confident assessment that each could be properly identified.

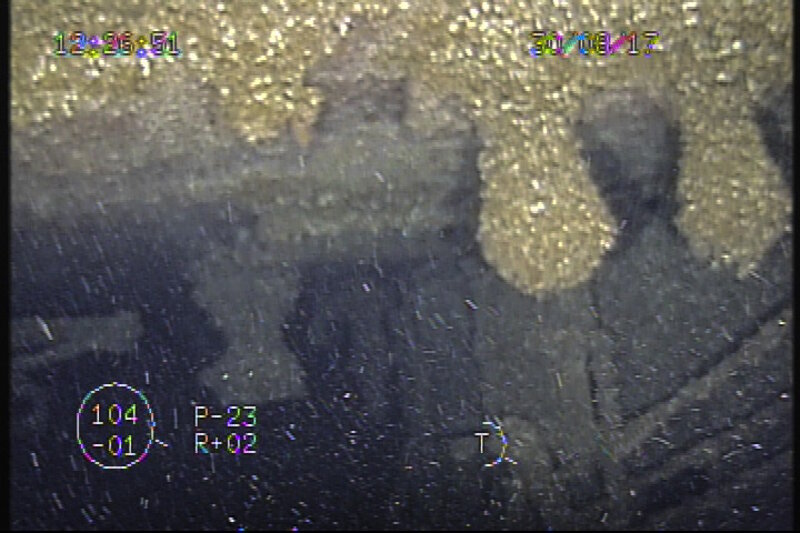

A view of Choctaw’s stern deck from underneath the upturned portion of its hull. This was a perspective that the sonar systems, limited by shadows, could not image. Features within this area match those of Choctaw’s deck and layout plans. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 239 KB).

Although these new shipwrecks are tentatively identified as Ohio and Choctaw, additional research is needed to complete their stories. At least one major question looms: where are the remains of schooner barge Ironton that tragically collided with Ohio? Historical accounts recorded them sinking quickly, which implies their remains would be close to one another. Yet, the survey conducted this summer revealed no such associated remains within the vicinity of Ohio’s final resting place. Only continued exploration will tell.

A pilot house is clearly visible at the bow of Ohio. Just forward of the pilot house is a capstan. The positioning of the pilot house is typical of early bulk freighters. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 168 KB).

As the sanctuary explores new areas, these kind of discoveries will continue to challenge archaeologists. Advances in remote sensing technology will aid in discovering and documenting new underwater archaeological sites, while the challenging conditions of working within the Great Lakes will remain an equally formidable and rewarding obstacle.

Finding new sites, however, is merely the beginning of a long process of resource monitoring, management, and research. Information gained from these discoveries, as well as underwater sites already known, is brought to the public through museums such as the Great Lakes Maritime Heritage Center in Alpena, Michigan, and also through an ever growing array of digital formats. Vessels once lost beneath the lakes come back to life as 3D models, virtual reality scenes, photo mosaics, archaeological site plans, and the attending interpretation of archaeologists, historians, and educators.

Hans VanSumeren (left, front) and John Lutchko (right, front) of Northwestern Michigan College work together while piloting an ROV during investigations of newly discovered shipwreck sites in Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary during August, 2017. Members of the Michigan State Police Marine Services Team, who also participated in the investigations, observe the operations onboard NOAA vessel R-5002. Image courtesy of Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary/NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 7.1 MB).

Like most sites in the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary, these new discoveries will likely meet the criteria of significance for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places. As more research progresses, sanctuary archaeologists will prepare the nominations while learning more about each vessel’s history and remains.

Public access to sanctuary resources, through Great Lakes Maritime Heritage Center exhibits, web and social media, or actual site visitation remain one of the highest sanctuary priorities. Anyone, from those viewing a web page in the comfort of their home, to those who will SCUBA dive down to the vessels in person, can share in the rich maritime history and heritage of the Great Lakes.

At the very far end of the vessel—its stern—a pointed terminus. This is a very diagnostic feature of whaleback-type vessels in general, and of Choctaw in particular as per its deck plans. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 290 KB).

Another observed feature consistent with Choctaw’s deck plans: a rounded back along the lower deck of the stern cabin. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 288 KB).

Three features of Choctaw’s stern cabin that match with historical images: a square window, ladder, and doorway situated just beneath the point where the funnel, connected to the smoke box uptake in the vessel’s boiler room, protrudes from the cabin. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 222 KB).

Looking slightly downward from the previous Choctaw image, the bottom of the funnel is seen where it passes through the stern cabin. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 225 KB).

The forward edge of the Choctaw stern cabin with its well defined overhang. Just forward (right) in the image is the aft-most cargo hatch. These features match very closely with the vessel’s deck plans and historical photographs. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 212 KB).

This image, captured by ROV, shows the last visible cargo hatch underneath the ship before it become buried in sediment at the bottom of Lake Huron. According to Choctaw’s plans, four more hatches and the bow structure remain embedded in the lake bottom, not visible along the surface. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 218 KB).

A buckled, collapsed area of Choctaw’s hull bottom. This is in the area where historical accounts reported steamer Wahcondha and Choctaw collided. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 329 MB).

Separated from the main vessel structure thought to be Ohio, ROV pilots from Northwestern Michigan College located the steam propulsion systems funnel and funnel cape along the bottom adjacent to the site via the ROV’s scanning sonar. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 335 MB).

Moving towards the bow of the vessel thought to be Ohio, ROV pilots followed standing rigging to reveal an intact foremast. These features included complete lower masts, mast heads, topmasts, rigging and intact trucks at the mast top. They were careful not to risk tangling the ROV in loose riggings and lines. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 190 KB).

Moving further forward on the vessel thought to be Ohio, the ROV pilots followed the mast’s forward stays down to the bow of the wooden bulk carrier. Ambient light was sufficient at this depth to silhouette features against light in the water column. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 172 KB).

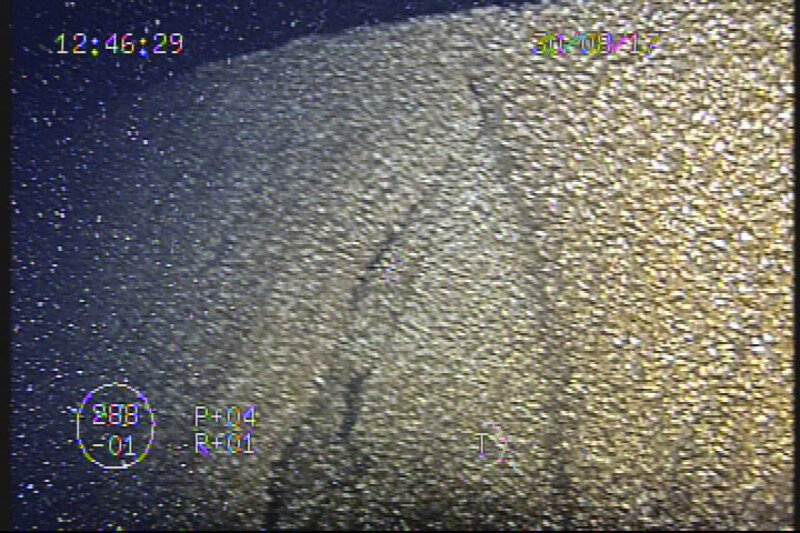

Moving in with the ROV for a closer look it is clear that the hull of the vessel thought to be Ohio is made from wooden materials. Image courtesy of Northwestern Michigan College/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 241 KB).

First sonar image of vessel now believed to be wooden bulk carrier Ohio, lost during a collision in 1894. This scan was obtained during exploratory archaeological survey operations off Presque Isle in May, 2017. Image courtesy of University of Delaware. Download image (jpg, 123 KB).

Labelled ‘Target 1’ when located in May, 2017, this site required additional survey before a more complete assessment was made. This sonar image, gathered in June, was produced by an AUV running perpendicular to the vessel’s bow. Intact masts and rigging are shown, as well as the round funnel, separated from the vessel’s stern cabin, are shown, as well as the hole in the vessel’s port quarter. This is tell-tale evidence of a collision. Image courtesy of Michigan Technological University/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

In this AUV pass over ‘Target 1’ the vehicle traveled directly over the midships section of the vessel. Here, two upright masts were well seen, one to the right and one to the left. The shadows of intact rigging are also visible around the bow (right). Image courtesy of Michigan Technological University/Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Download larger version (jpg, 2.0 MB).

Dates: Sites discovered 23 May 2017; investigated through June, July, and August, 2017

Discovery Partners:

NOAA’s Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary,

NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory

University of Delaware

Michigan Technological University

Northwestern Michigan College

Michigan’s Department of Natural Resources

Area of Exploration:

Historic shipping lanes off Presque Isle, Michigan, Lake Huron

Technology:

University of Delaware remote sensing system used for exploratory survey in May, 2017:

Vessels:

NOAA R8001, R/V Laurentian; NOAA R5002, R/V Storm