By Matt Poti, NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science

August 26, 2017

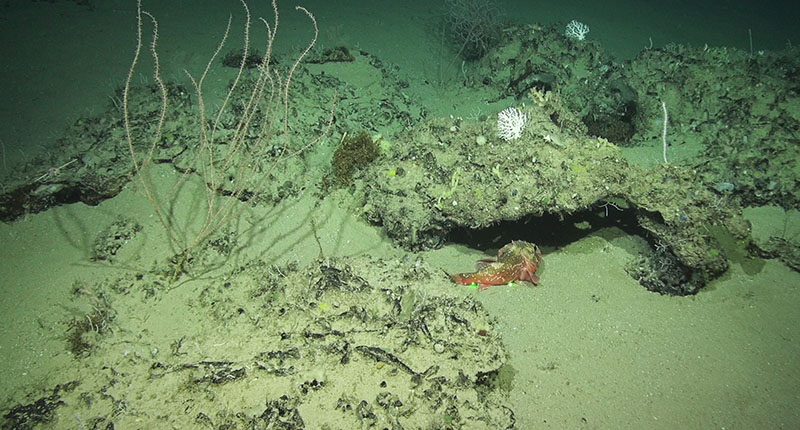

Colonies of bamboo coral (left), lace corals (center right), sea whip (right), and Leiopathes glaberrima black coral (back) at the proposed Habitat Area of Particular Concern site known as North Reed. Also shown is a blackbelly rosefish, with green lasers dots 10 centimeters apart. Image courtesy of NOAA Southeast Deep Coral Initiative and Pelagic Research Services. Download larger version (jpg, 480 KB).

Over the past five years, NOAA has developed regional models that predict which areas of seafloor habitat can support various types of deep-sea corals. Maps of 'habitat suitability' for these areas inform conservation and management of deep-sea corals and identify potential targets for future mapping and exploration. Therefore, it is important that we continue to evaluate how well these models predict suitable habitat and to improve them as additional information becomes available.

Expeditions supported by the Southeast Deep Coral Initiative are critical for ‘ground-truthing,’ as they collect fine-scale spatial data describing the locations where deep-sea corals are found, as well as where they are not found. These expeditions also provide insight into the environmental and oceanographic conditions surrounding deep-sea coral habitat.

For many of the dives on this expedition, the team has used remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Odysseus to explore mound features and a ledge that extends many hundreds of kilometers through multiple proposed habitat areas of particular concern (HAPCs) that are being considered for protection by the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council. Within the areas called Long Mound, North Reed, and Many Mounds, much of the ledge and surrounding area was predicted by our models to be highly likely to contain suitable habitat for the stony coral Lophelia pertusa and the black coral Leiopathes glaberrima.

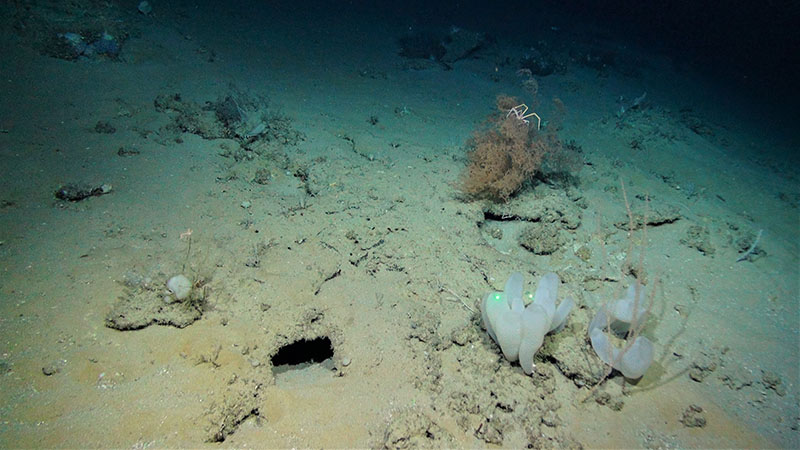

Low relief rocky substrate with bamboo coral, sponges (both lower right), Leiopathes glaberrima black coral colony, and a squat lobster (both top right) at the proposed Habitat Area of Particular Concern site, Many Mounds. Image courtesy of NOAA Southeast Deep Coral Initiative and Pelagic Research Services. Download larger version (jpg, 3 MB).

As you may have read in some of our earlier mission logs, we did in fact observe Lophelia pertusa and Leiopathes glaberrima at all of the proposed HAPCs we surveyed! These corals were found in predicted locations, as well as in locations where the models predicted we would not be likely to find them. In other cases, we did not find corals in areas where we expected them to occur. While this information is extremely valuable for evaluating the performance of our habitat suitability models, I came away from this expedition with a few observations that will be just as critical as we develop future versions of habitat suitability models.

Map comparing depth information along the West Florida slope collected from A) a multibeam echosounder on NOAA Ship Nancy Foster and B) the NOAA Coastal Relief Model. Color indicates depth, with red showing shallower areas and blue for deeper areas. Note that the mound and ledge features explored by the remotely operated vehicle Odysseus, operated by Pelagic Research Services, on this expedition are discernible in the high-resolution data depicted in A but not in the moderate-resolution data depicted in B. The illustrated area includes three proposed Habitat Areas of Particular Concern: a) Long Mound, b) North Reed, and c) Many Mounds. Image courtesy of Matt Poti, NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science. Download larger version (jpg, 432 KB).

First, in locations where we observed deep-sea corals, the densities of these coral colonies varied considerably. This is important to note because existing models do not indicate how abundant corals are likely to be. In addition, while we observed deep-sea corals on high relief, hard substrate along the ledge or on large mounds in some locations, in others we observed deep-sea corals clinging to relatively small patches of rocks (see images above). These smaller seafloor features are indiscernible in moderate-resolution maps of seafloor depth, such as the NOAA Coastal Relief Models. This finding emphasizes the need for gathering finer-scale depth information using multibeam echosounders or autonomous underwater vehicles to help us build the next generation of 'super models' for deep-sea corals.

The expedition is supported by NOAA’s Deep Sea Coral Research and Technology Program through the Southeast Deep Coral Initiative (SEDCI), a multi-disciplinary effort that will study deep-sea coral ecosystems across the Southeast United States in 2016-2019.