by Dr. Martha Nizinski, Zoologist, NOAA Office of Science and Technology, National Systematics Laboratory

Dr. Anna Metaxas, Professor, Dalhousie University

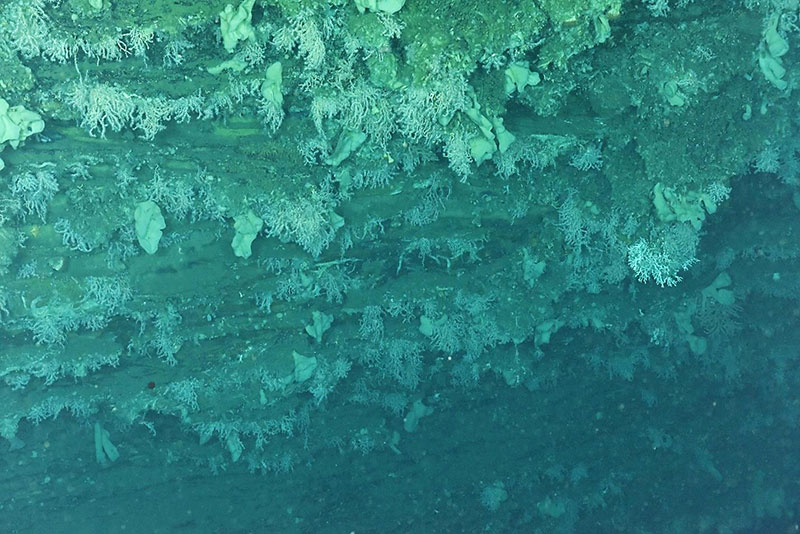

Corals (mostly Anthothela) and sponges cover the wall of the unnamed minor canyon between Nygren and Heezen canyons. Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download larger version (jpg, 602 KB).

On June 9, 2017, an international team of scientists aboard NOAA Ship Henry B. Bigelow left the dock at Naval Station, Newport, Rhode Island, en route to canyons off the coast of New England and Atlantic Canada, as well as the shallower shelf habitats in the northern Gulf of Maine. Our mission objectives included surveying transboundary canyon, inter-canyon slope, and Gulf of Maine shelf areas to characterize sensitive benthic habitats, particularly deep-sea coral habitats; conducting multibeam mapping in areas where data were missing or incomplete; ground-truthing and validating the deep-sea coral habitat suitability model; collecting samples to support a variety of projects; and sharing our findings through education and outreach initiatives.

The data collected during the expedition not only support our science but also provide resource managers with information to better inform management and conservation actions. In fact, the majority of our sampling locations were selected based on the data needs of the New England Fisheries Management Council and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Over the course of our two-week mission, we surveyed four canyons, one site on the continental slope, and two sites on the continental shelf in the Gulf of Maine using the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) ROPOS, operated by the Canadian Scientific Submersible Facility. At each of these sites, we were able to meet our objectives, collecting high-definition video and still imagery to document deep-sea coral presence, distribution, abundance, and diversity, as well as species associations. Samples were taken at every station: corals were collected for taxonomic, genetic (population genetics and connectivity studies), and reproductive biology analyses. Additionally, heavy metal and isotopic analyses will be conducted on coral samples to investigate the variability of water mass composition and inputs of anthropogenic (human) sources of carbon dioxide. Other invertebrates, including cephalopods, shrimp, squat lobsters, bivalves, anemones, and a nudibranch (likely a species new to science) were collected to verify the taxonomic identification of these species as well as contribute to several ongoing taxonomic, ecological, and genetic studies. In muddy areas, sediment cores and water samples were collected to document infaunal diversity—from microbes to meiofauna to macrofauna. Experiments were conducted to address nutrient cycling within the soft sediments.

Red fish congregate around a large boulder colonized by the corals Anthothela (pink) and Paramuricea (yellow) as well as some anemones in Georges Canyon (Canada). Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download larger version (jpg, 755 KB).

Although frustrating to see the ROV ROPOS sitting on the deck when bad weather closed down these operations, “weather days” were not a lost cause. Multibeam mapping operations by the Bigelow turned a disappointment into a much needed data product. Portions of three areas of high priority for resource managers in the Gulf of Maine (Outer Schoodic Ridge (U.S.), Mount Desert Rock (U.S.) and Central Jordan Basin (Canada)) were mapped when the sea state was a bit too rough to deploy the ROV safely.

It is hard to believe that an area as well-known as the Gulf of Maine does not have adequate, high-resolution maps of the seafloor. Given deep-sea corals are more likely to occur in areas of high topographic relief in the Gulf, these high-quality bathymetric maps will help us locate and predict where corals are likely to occur which will then lead to better informed management decisions.

We continue to learn more about deep-sea ecosystems: every mission, every dive, adds to our knowledge base, fills in data gaps, and helps us build a more complete understanding of deep-sea corals and their contribution to the structure and function of the deep sea.

We found that minor canyons in U.S. waters harbor some amazing coral habitats. Large colonies of Lophelia pertusa were discovered at around 750 meters growing along the edge of rocky ledges and under overhangs. This is the most Lophelia we have seen in the northern canyons to date. Our second visit to Corsair Canyon in Canadian waters illustrated that there are more habitat types represented on the walls of Corsair than the large, beautiful colonies of the deep-sea octocoral Paragorgia we discovered in 2014. Our first look at neighboring Georges Canyon revealed mud cliffs and few corals. Fiddlers Cove, our last stop along the continental slope, is located near Canada’s Northeast Channel Discovery Corridor. Our results will help inform managers as they discuss possible expansion of this marine protected area. Surveys in the Gulf of Maine lead to the discovery of more coral gardens in less than 200 meters of water. Comparing these locations with known coral garden sites will give us a better idea of where coral gardens are likely to occur and how we can better protect them.

NOAA Ship Henry Bigelow heads home through the Cape Cod Canal. Image courtesy of Frank Ruscito. Download larger version (jpg, 422 KB).

This expedition was our second transboundary collaboration, building on our highly successful 2014 mission. Unlike some movies, the sequel was just as successful! As we continue to add to our knowledge of deep-sea coral habitats, we can begin to formulate hypotheses for some higher level questions. Additionally, results from this mission went directly to the fishery management council and federal agencies tasked with managing our marine resources. Thus, close ties are maintained between the efforts to conserve and the scientists dedicated to studying these habitats.

The success of these missions has strengthened the collaboration between the U.S. and Canadian scientists involved. We are committed to learn more about our shared resources in the region. Is there another mission in our future? Stay tuned—a resounding "yes" was heard on both sides of the border.