by Matt Poti, NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science

June 20, 2017

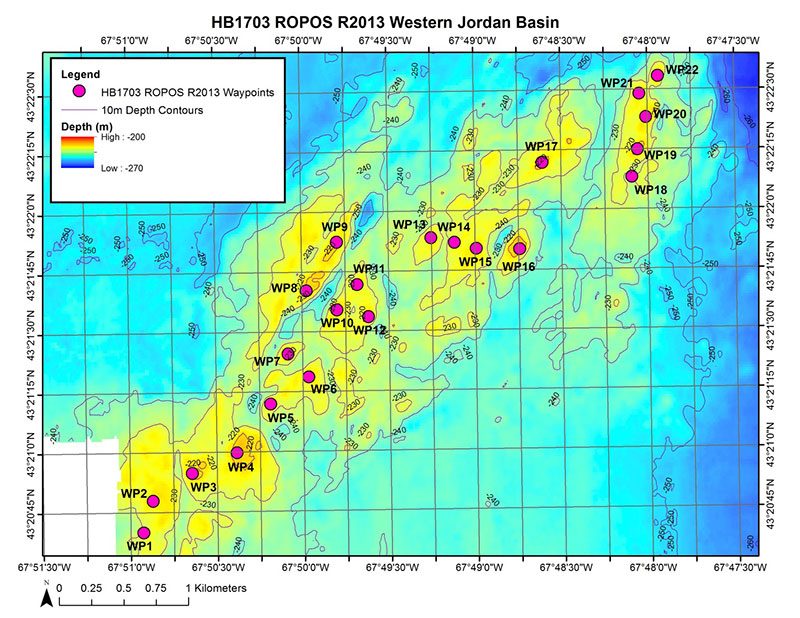

Example of a day’s dive plan map for a ROPOS survey, Western Jordan Basin, Gulf of Maine. “WP” means waypoint along a transect. Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

A typical dive plan for one of our surveys with the ROPOS remotely operated vehicle (ROV) looks straightforward. It includes a series of waypoints, which are the coordinates used to navigate ROPOS along the intended path; information on the kinds of sampling that may occur during the survey; and a map of the waypoints overlaid on data depicting the depth of the seafloor in the survey area.

Simple, right? In fact, surveying for deep-sea corals and sponges is expensive and logistically challenging. The process of planning one of our surveys is not often straightforward and can be complicated by the lack of existing data for areas that haven’t yet been explored. In spite of these limitations, the science team needs to identify areas for surveying where we’re likely to find these organisms in order to make the most of our short time at sea.

Prior to each ROV survey, the science team identifies potential targets. My role on the science team is to analyze the existing data for each location so I can help the science team choose survey transects that are likely to pass over prime habitat for deep-sea corals and sponges. I begin by compiling depth data from any multibeam surveys available for these areas. I use this data to calculate how steep and complex the seafloor is in order to locate places within the target area that have relatively high slopes and that have complex topography—habitat that deep-sea corals and sponges seem to prefer.

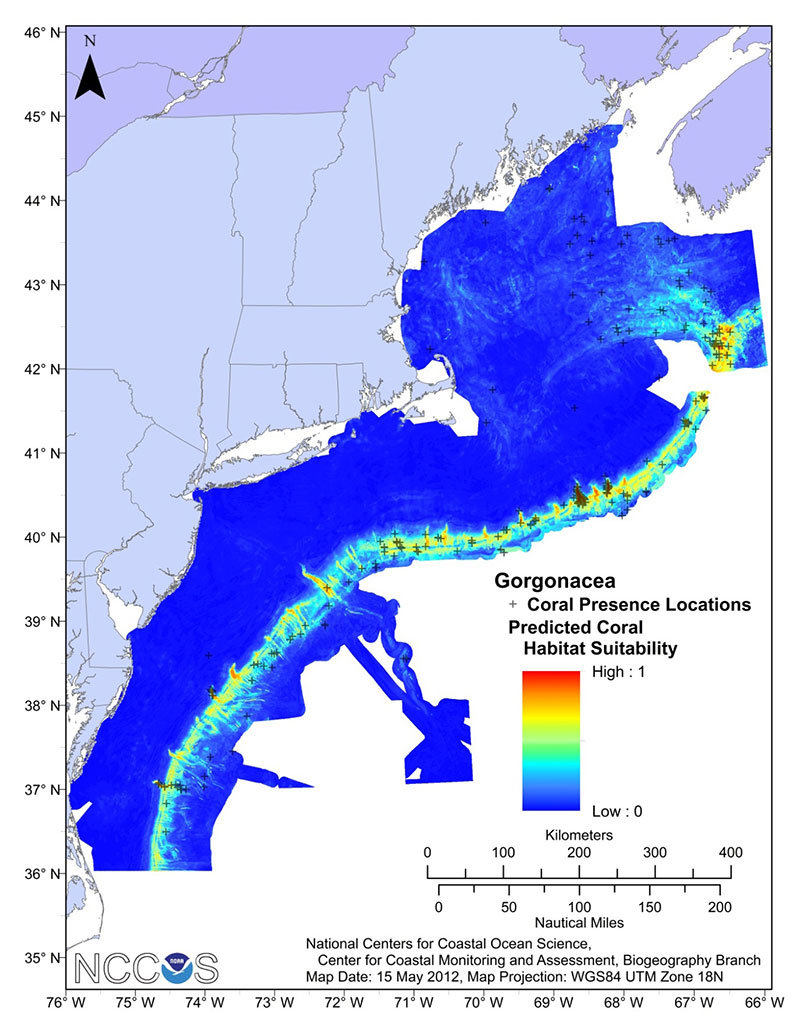

Another tool that I use is habitat suitability modeling, which has become a cost-effective method to identify potential locations of deep-sea corals and other species and aid managers in determining deep-sea coral management zones. In these models, we use data describing the environmental and oceanographic conditions at locations where deep-sea corals have been observed to predict locations on the seafloor that may be capable of supporting different types of deep-sea corals. For example, models derived for gorgonian corals predict that many of the submarine canyons we’re exploring are highly likely to contain suitable habitat for them. I then typically combine information from the model predictions with features identified in the analysis of the available depth data to select specific targets for the ROPOS surveys.

In order to evaluate how well the models can predict the likelihood of suitable habitat for deep-sea corals, we need to validate them by collecting additional data in locations predicted to be both suitable and unsuitable habitat. Deep-sea coral observations from missions like this are critical for this purpose. We’ve also had considerable success using the habitat suitability models to help plan our previous deep-sea coral surveys, with the models showing that they could consistently predict suitable deep-sea coral habitat in the vicinity of known deep-sea coral presence locations as well as in previously unsurveyed areas.

These habitat suitability models, along with maps of depth from multibeam surveys and deep-sea coral distribution data from historical and recent surveys, have become essential tools that our regional U.S. Fisheries Management Councils use to help them determine the locations of deep-sea coral protection zones.

Example of a habitat suitability model for gorgonian (sea fan) deep-sea corals in the Northeastern U.S. region. Warm colors (e.g., red) denote areas predicted to be more suitable coral habitat and cooler coolers (e.g., blue) denote areas predicted to be less suitable coral habitat. Crosses represent coral presence records used in generating the model. Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download larger version (jpg, 967 KB).