by Dave Packer, NOAA Marine Ecologist

June 18, 2017

Deep-sea corals Primnoa (pinkish) and Paramuricea (yellow) on a steep wall in Western Jordan Basin, U.S. Gulf of Maine. Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download larger version (jpg, 488 KB).

Chief Scientists’ weather report: Cloudy with a chance of showers, with isolated patches of the finest corals you’ve ever seen.

“Toto, we’re not in canyons anymore.”

Today we returned to U.S. waters in the northern Gulf of Maine to survey a site in western Jordan Basin. During today’s dive, we surveyed a number of high relief hard-bottom “bumps” that could be good coral habitat but that we hadn’t surveyed previously. Our overall objectives were to document the existence and extent of these habitats, as well as collect specimens for genetics, reproduction, aging, and taxonomy. The deep-sea coral habitats in the U.S. Gulf of Maine are quite different from those in the canyons.

First, the Gulf of Maine is a large semi-enclosed continental shelf sea that is ecologically separate from the Atlantic Ocean. Deep-sea corals in the Gulf of Maine have been reported since the 19th century, both as fisheries bycatch and from naturalist surveys. While at one time they may have been considered common on hard-bottoms in the region, after a century of intensive fishing pressure, the more dense populations of deep-sea corals and coral habitats are now confined to small areas where the rough bottom topography makes them mostly inaccessible.

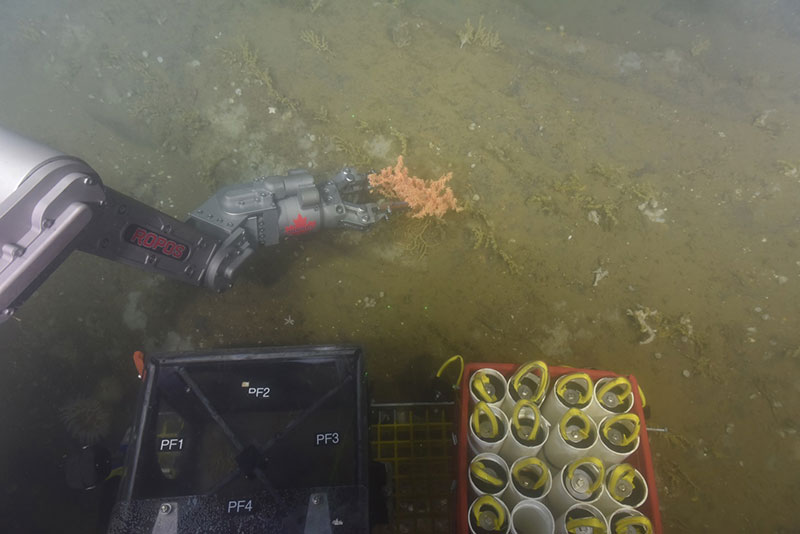

The ROPOS arm collecting a small piece of Primnoa coral in Western Jordan Basin. It will be stored in one of the “quivers” on the right until the ROPOS returns to the surface. Note the yellow Paramurica on the outcrop as well. Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download larger version (jpg, 484 KB).

The major difference between deep-sea coral habitats in the canyons and Gulf of Maine is that the canyons, continental slope, and seamounts are where we find large, and potentially the oldest, corals, as well as the higher coral biodiversity. Contrast that with the Gulf of Maine where only two or three species commonly occur. However, dense and extensive “coral gardens” have been observed at only 200-250 meters depth, especially in areas of high vertical relief.

The predominant structure-forming corals on hard-bottoms in the Gulf are gorgonian corals, also known as sea fans. Paramuricea is the major coral species found in Western Jordan Basin and is found in high densities on the steeper hard-bottom areas, although it will attach to any hard substrate, pebbles covered in soft sediment for example, as well as cobbles and boulders. Primnoa and Acanthogorgia are mostly found on high relief hard-bottom areas, including vertical faces or walls. Studies by Dr. Cheryl Morrison and others show that Primnoa populations in the Gulf are genetically distinct from those in the far offshore canyons.

Primnoa hanging from a large outcrop in Western Jordan Basin. Note redfish sitting among the coral, middle-right in image. Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download larger version (jpg, 420 KB).

Today’s dive certainly did not disappoint: in several previously unexplored high-relief bumps or outcrops, we found beautiful and magnificent assemblages of Primnoa and Paramuricea; some of these areas of densely packed coral colonies went on for tens of meters. But there’s another telltale difference between the Gulf’s coral habitats and those in the canyons: the amount and types of fish associated with them. In the canyons, you’ll find many deepwater fishes, like the abundant cutthroat eels, as well as some commercially important ones, like Acadian redfish or monkfish. In the Gulf of Maine, you’ll find many more of our commercially important fish and shellfish species, including redfish, haddock, cod, and silver hake.

The high densities of Paramuricea and Primnoa observed today in the relatively shallow waters of the Gulf of Maine are unique off the northeast United States. The proximity of these habitats to shore increases the likelihood that they are important for our commercially important fish, thus increasing the need to protect and preserve these fragile habitats.