by Dr. Paul Snelgrove, Memorial University of Newfoundland

June 13, 14, 2017

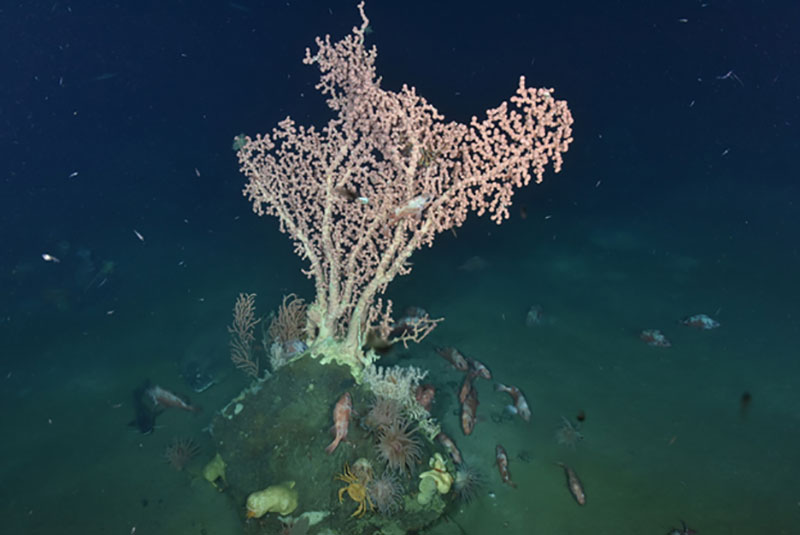

Large and very old bubblegum coral Paragorgia arborea on a rock, along with red crab and venus flytrap anemones, in Corsair Canyon. Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download image (jpg, 217 KB).

Returning to Corsair Canyon for the first time since our last visit in 2014 generated excitement among the science team that had been involved in our previous visit. The data we collected on that dive helped Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s decision to close Corsair Canyon to protect fragile resident corals that grow slowly and damage easily when disturbed by fishing gear. This decision illustrated how our basic science work can actually produce changes in ocean policy and promote conservation efforts. But the main goal for us this time was to see other unexplored areas of the canyon.

For this expedition, ROPOS surveyed the seafloor for close to 12 hours, and although we expected to see coral based on the complex topography, we mostly saw rolling plains, steep slopes, and even cliffs of sediment-covered seafloor. The few rocks we saw were often densely covered with several species of deep-sea corals, indicating that the absence of hard substrate clearly limits coral abundance here for those types of corals that colonize and require hard substrate.

Large bubblegum coral Paragorgia arborea, along with Primnoa (orange, behind on left) and Anthothela (white, on right) corals on a rock in Corsair Canyon. Also Acadian redfish, longfin hake (black, on left side of rock), and Atlantic halibut (flatfish behind and to right of hake). Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download image (jpg, 186 KB).

Twelve hours of mud can get pretty monotonous, but my students and I study the rich biodiversity that lives in mud, and the role that diversity plays in recycling food particles that sink down from surface waters, which regenerates nutrients and drives ocean production. In the end, our patience was rewarded as we saw the visible megafauna change from landscapes with numerous pink anemones to others dominated by feathery sea pens (which are actually a type of deep-sea coral that lives in soft sediments) bending in the currents.

The next day, we moved to nearby Georges Canyon, which we had never explored before, and had another day with few corals and lots of mud. But we did see amazing mud cliffs with complex burrows likely made by crabs and fish. We also saw dense aggregations of sea pigs, Scotoplanes, which is a type of echinoderm (echinoderms include sea stars, brittle stars, and sand dollars) known as a holothurian. These aggregations were unlike anything we had seen before, as they danced off the seafloor to intermingle with a passing school of squid.

Dense aggregation of sea pigs (Scotoplanes), a type of echinoderm known as a holothurian, in Georges Canyon (Dive 1). Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download image (jpg, 196 KB).

To conserve and sustain ocean health and function, conservation efforts should include representative habitats as well as charismatic species. Sediments cover more ocean floor than all other benthic habitats combined, and thus represent a large portion of our planet. One ocean but many different habitats. All merit study and conservation effort.