by Dave Packer, NOAA Marine Ecologist

June 12, 2017

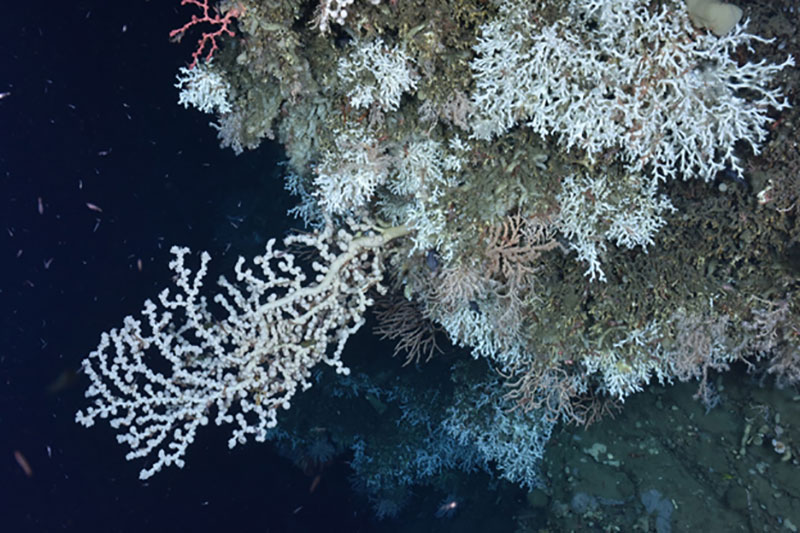

A variety of deep-sea corals found on a ledge in an unnamed canyon between Heezen and Nygren Canyons, including the stony coral Lophelia pertusa, a large white gorgonian Paragorgia (bubblegum coral) and a small red Paragorgia (upper left), and the gorgonian Primnoa (orange, center). Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download image (jpg, 287 KB).

Chief Scientists’ weather report: cool and breezy, with an 80% probability of WOW THIS IS INCREDIBLE!!!

Day 3 of our ROPOS dive surveys went off without a hitch. This time, we dove on an unnamed “minor” canyon between Heezen and Nygren canyons in U.S. waters. Our intention was to survey the eastern wall of the canyon in an up and down, zig-zag pattern.

We dropped down to our first waypoint, a relatively deep location close to the head of the canyon and at the bottom of the wall at 838 meters depth. First task was collecting sediment core samples for Dr. Paul Snelgrove and Marta Miatta. Once all the cores samples were taken and safely stowed on board the remotely operated vehicle (ROV), we headed toward and up the eastern wall.

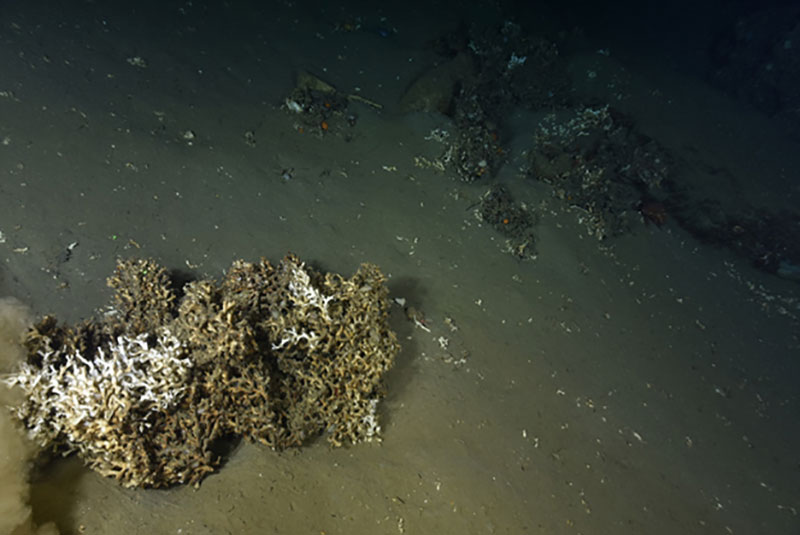

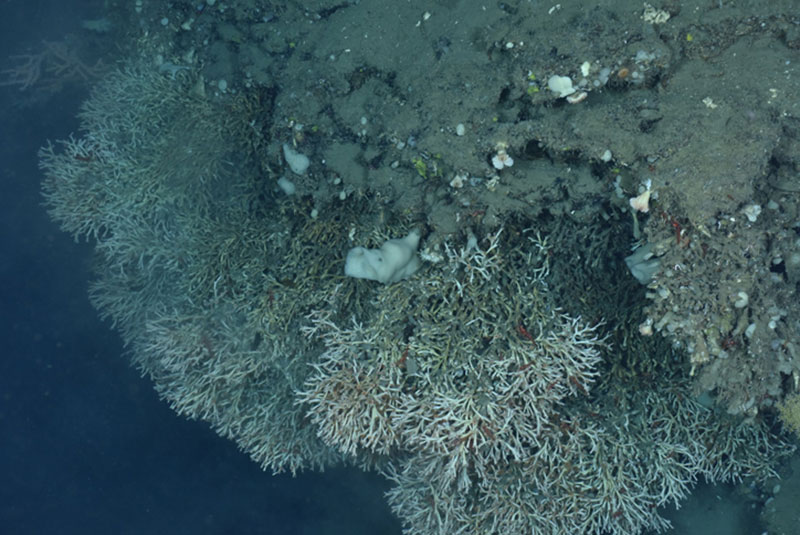

We quickly discovered that this “minor” canyon was anything but minor. On the lower slopes of the wall, in the flatter and muddier areas, we came across large amounts of big, boulder-like chunks of dead Lophelia (stony coral) skeletons, followed by debris fields of dead Lophelia pieces and colonies. Realizing that these must have come “from somewhere up above,” we continued our transect up the wall. What we found next caused everyone who was watching to shout in astonishment. There were incredible amounts of Lophelia colonies, often densely packed, and hanging from ledges and terraces and overhangs, some rather large, and swarming with other invertebrates. No one had seen this much Lophelia this far north.

Example of a large detached block of mostly dead (brown skeleton) stony coral Lophelia pertusa on the seafloor of an unnamed canyon between Heezen and Nygren Canyons. Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download image (jpg, 202 KB).

Many, if not more, of the corals we had seen previously, also resided here in high abundance. Primnoa, although relatively common, hadn’t been seen on the previous dives, and there was even an “unusual” one that we didn’t quite recognize. Also, we had only seen really small, pinkish Paragorgia (“bubblegum” coral) previously, now we finally saw some larger sizes. And of course, an amazing variety and amount of sponges here as well. But the sheer amount of corals and sponges we found as we surveyed this area was astounding. We collected specimens for genetics, reproduction, and taxonomy studies, especially of Lophelia.

But why is Lophelia so important? Although it’s found around the world and reported from Canadian waters, only recently has Lophelia been found in any abundance in the canyons off the U.S. northeast coast. Only by using sophisticated survey vehicles like the ROPOS ROV can we thoroughly explore complex habitats such as these. Lophelia is important because it forms a hard structure, thus providing a shelter and substrate for other organisms. Off North Carolina, it even forms deep-sea reefs hundreds of feet long.

Several colonies of the stony coral Lophelia pertusa on a ledge in an unnamed canyon between Heezen and Nygren Canyons. Image courtesy of Northern Neighbors: Transboundary Exploration of Deepwater Communities. Download image (jpg, 344 KB).

Scientists like Dr. Cheryl Morrison are studying genetic connectivity of Lophelia between populations and geographic areas. In other words, are Lophelia from one area of the ocean similar or different to those in another area? This information is important when considering the best design and placement of protected areas that may allow regional populations to persist, and research cruises like this one will provide the samples to do the research that will answer these questions.