By Dr. Jason Chaytor, U.S. Geological Survey, Research Geologist

September 20, 2017

The autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) Sentry collects a large amount of geophysical data (bathymetry, side-scan and sub-seafloor reflection profiles) during each 18- to 24-hour dive, all of which needs to be processed from streams of 1’s and 0’s into correctly located maps and other visual representations of the seafloor and sub-seafloor.

After each dive, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Sentry group copies the several terabytes of raw and preliminarily processed data from the vehicle to our data storage servers (made four-times faster after the first dive by the efforts of the Pisces ET Patrick Bergin) from where we begin the process of feeding the individual data types into several different processing workflows.

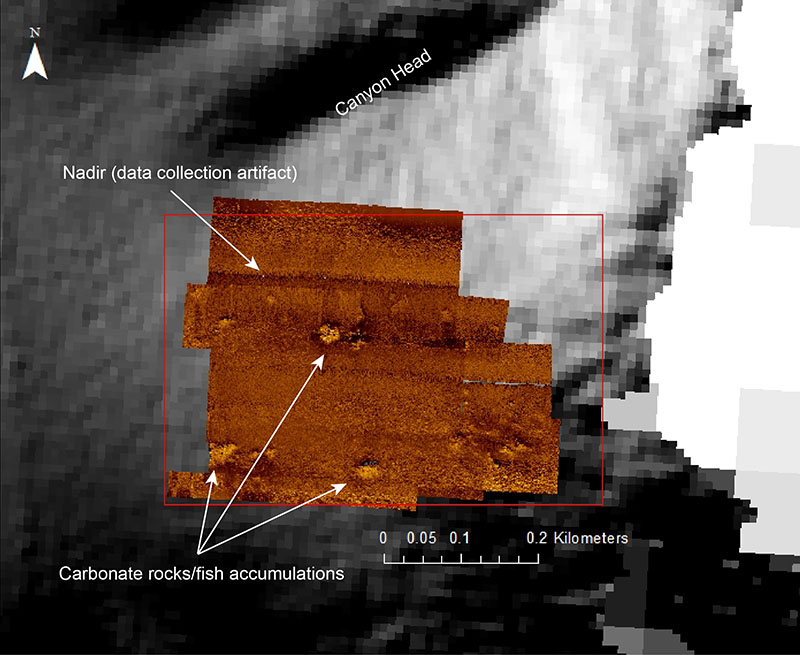

Processed side-scan mosaic over one of the focused survey sites. Several prominent features are present in the mosaic that correspond with carbonate rocks and fish aggregations seen in the photographs taken by Sentry during the same survey. Light colors represent harder material, while darker colors represent soft materials (i.e., sediment). Image courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2017, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

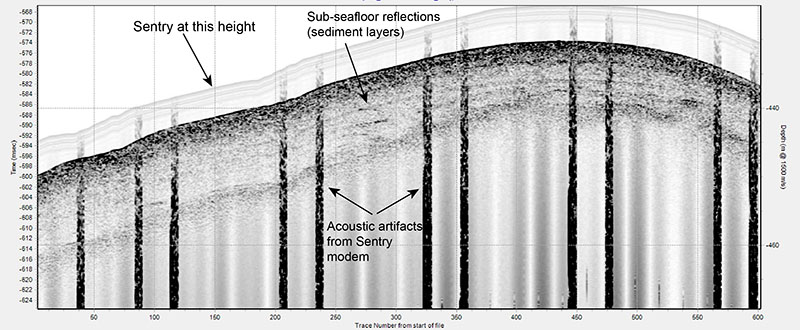

For this cruise, I am primarily responsible for processing the high-resolution side-scan sonar and sub-bottom profiler data collected by the Sentry. Side-scan sonar imagery is somewhat analogous to a photo of the seafloor, but rather than using light to make the image, it uses the strength of reflected sound from hard (e.g., rocks) and soft (e.g., sediment) seafloor. Similarly, the sub-bottom profiler uses sound (but at a much lower frequency) to penetrate the seafloor surface and reflect off of different layers of sediment, rocks, or even gas buried below to show us what is hidden from view in the first few tens of meters below the seafloor—providing a 3D view of the seafloor environment.

Processing each of these data types requires several software programs, user experience in identifying real data versus collection and processing artifacts (errors), and a lot of patience. When these data are combined with the seafloor photographs and environmental data collected by Sentry and the acoustic data collected by the Pisces, a remarkable picture of the oceanographic, ecological, and geological setting can be produced.

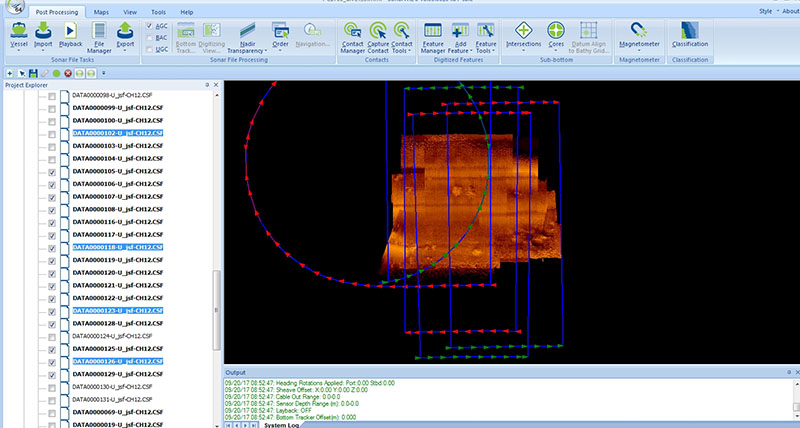

Screen capture of an intermediate stage of building the side-scan mosaic. The blue lines and arrows show the bounds and port (red arrow) and starboard (green arrow) sides of the individual imagery files collected by Sentry. At this stage, the outside edges of the individual images have been trimmed to remove parts of these data outside the visible range and the intensities of the acoustic returns have been compared and normalized. Image courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2017, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 543 KB).

Side-scan sonar data records are processed to remove data from when Sentry was turning and to correct for the different vehicle orientations and heights above the seafloor, changes in seafloor gradient and slope direction, and the angles at which the sound is transmitted and received. After these initial steps, production of an interpretation-ready image is a little like assembling a jigsaw puzzle—the final large image is a mosaic of different bits and pieces of the smaller individual Sentry survey line images. Where there are prominent features on the seafloor, such as rocks, seep communities, and canyon walls, this task is somewhat straightforward as features can be matched between adjacent or overlapping images. However, when only subdued features are present (small holes or depressions in the seafloor), the task is quite challenging.

Screen capture of one of the preliminary processed sub-bottom profiles collected by the AUV Sentry during Dive 455. In this profile, sub-seafloor layers (stratigraphy) are visible as are several of the data artifacts that remain to be removed. Sentry transited at approximately six meters above the seafloor when these data were collected. Image courtesy of DEEP SEARCH 2017, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

Processing of sub-bottom profiler records follow a less complicated path...at least initially. On the ship, we are only processing these data to the point of being able to identify features such as different sediment layers below the seafloor or to pinpoint locations of seeps where they are coming out of the sediment. Back on shore, we will continue to process these data to remove as much of the noise from Sentry’s other acoustic instruments as possible, while trying to enhance the reflections from the water-column and sub-seafloor features for more detailed analysis.