By Michael Studivan, PhD Student, Integrative Biology - Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute at Florida Atlantic University

May 23, 2017

Taking a bite out of an Agaricia agaricites colony with the ROV manipulator jaws. The jaws exert nearly 50 pounds of force and can break off thin margins of coral colonies. Image courtesy of Cuba’s Twilight Zone Reefs and Their Regional Connectivity. Download larger version (jpg, 534 KB).

Beyond exploration of new mesophotic reef habitats and characterization of community composition across depths, our expedition includes another important research objective: to sample benthic species, including a diverse collection of corals, sponges, and algae.

PhD Candidate Michael Studivan using the ROV toolsled controls to collect corals, sponges, algae, and carbonate rocks for taxonomic identification and genetic research into connectivity across mesophotic coral reefs in Cuba and the U.S. Image courtesy of Cuba’s Twilight Zone Reefs and Their Regional Connectivity. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

All of these samples are being shared among U.S. and Cuban scientific counterparts, with some subsamples preserved for taxonomic identification and others for future genetic research. In particular, the Robertson Coral Reef Program at Florida Atlantic University Harbor Branch led by Dr. Joshua Voss is anticipating the collection of enough tissue samples of the coral species Montastraea cavernosa to aid in ongoing population connectivity analyses.

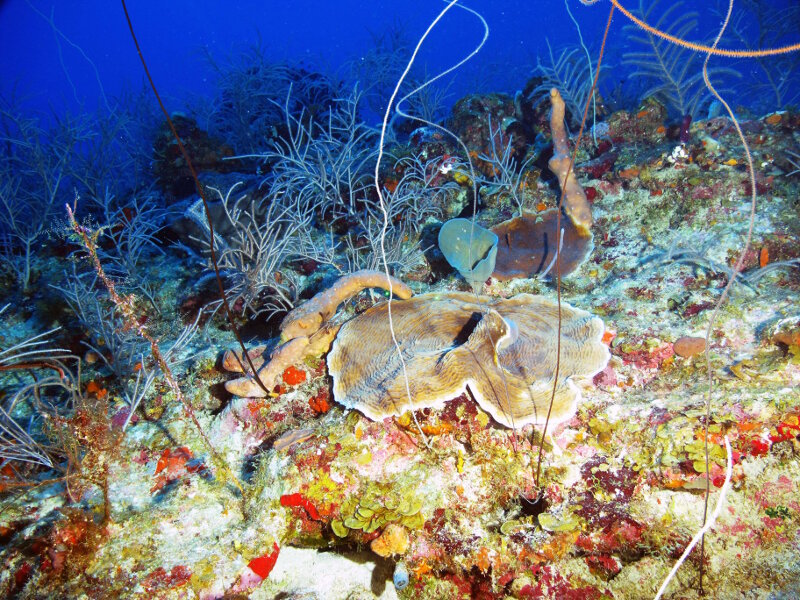

Scleractinians such as Agaricia spp. cohabitate with gorgonians (soft corals) and antipatharians (black corals) along the top of the upper mesophotic zone at 50 meters depth. Mesophotic reefs are truly unique environments where species from both shallow and deep depths can be found. Image courtesy of Cuba’s Twilight Zone Reefs and Their Regional Connectivity. Download larger version (jpg, 2.5 MB).

Montastraea cavernosa is ubiquitous across the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean and is considered a depth-generalist coral, meaning it can be found across shallow and mesophotic habitats. For my dissertation research, I have chosen to focus on M. cavernosa for a Gulf-wide assessment of coral population structure, gene expression responses to the environment, and morphological variation across shallow and mesophotic depths.

We have collected samples from Belize, the Flower Garden Banks, McGrail and Bright Banks in the northwest Gulf, Pulley Ridge in the southeast Gulf, and the Dry Tortugas. Genetic differentiation is low across these sites and depths, despite thousands of kilometers between the reefs. Perhaps most interestingly, shallow reefs in Belize are genetically similar to those in the Dry Tortugas.

Given that the western end of Cuba is directly in the middle of dominant currents between these two regions, we hypothesize that Cuban reefs play an important role in connecting M. cavernosa populations across the eastern Gulf of Mexico. It is also possible that Cuban reef populations may share genetic connectivity with other sites, including marine protected areas in the Flower Garden Banks and Pulley Ridge. Our contribution to the Cuba Twilight Reef project is the determination of coral population dynamics across the Gulf as a region, using a widely dispersed, depth-generalist coral as a model species.

In addition to our primary coral sampling focus with Montastraea cavernosa, we are also attempting to collect Agaricia spp. samples for taxonomic and genetic identification. Species within this genus are notoriously hard to differentiate, and limited genetic studies have indicated that current species denominations may be incorrect. Using the coral samples collected on this expedition in conjunction with those already collected across the Gulf, we hope to better delineate species boundaries for improved taxonomic identification.

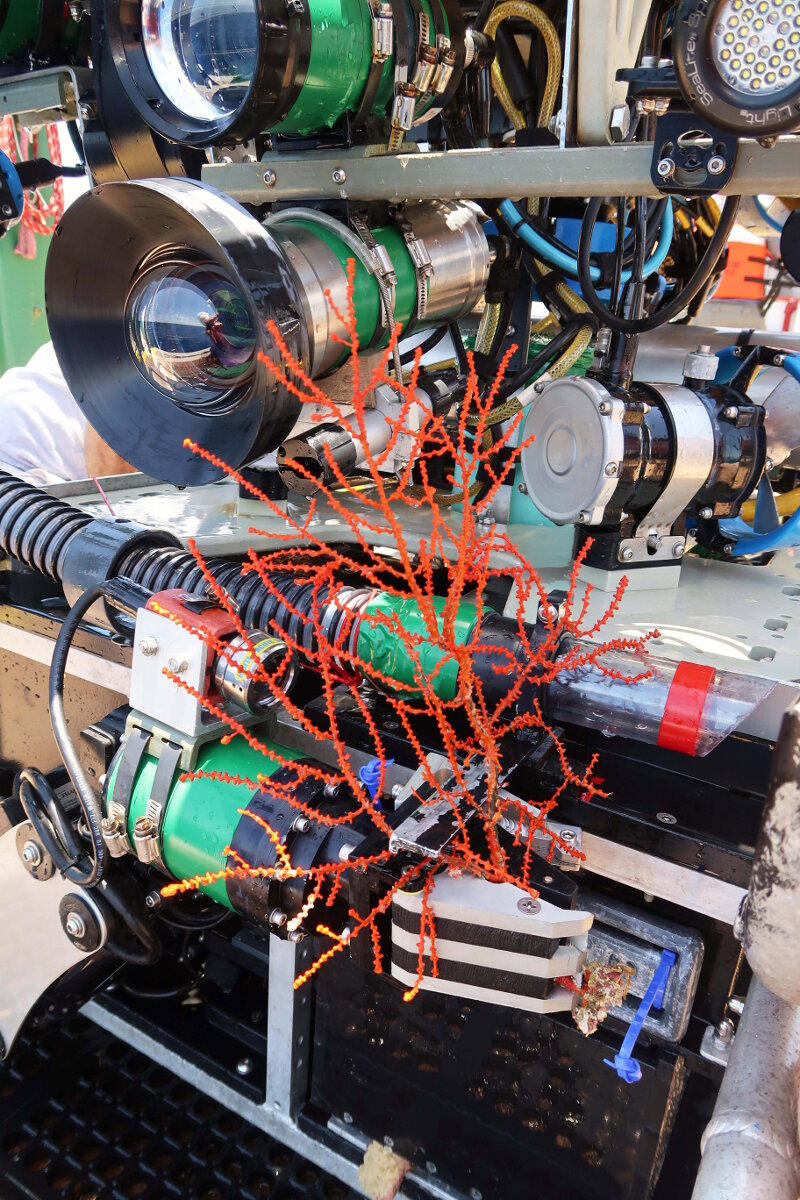

Some samples such as this Swiftia exserta collected at 70 meters are too big to fit in the bioboxes or suction buckets, and have to be carried up to the surface in the manipulator jaws. Hold on tight! Image courtesy of Cuba’s Twilight Zone Reefs and Their Regional Connectivity. Download larger version (jpg, 2.7 MB).

Lastly, we are collecting gorgonians (soft corals) and antipatharians (black corals) for verification of species identification from remotely operated vehicle (ROV) video. Species within these groups are often difficult to identify without time-intensive examinations of microskeletal spicule structures, which require tissue samples.

Corals are the most challenging of all the species we are collecting on this expedition. Whereas sponges and algae are usually soft bodied and can be grabbed either with the manipulator jaws or the suction hose, corals first require a strong force to break off a fragment from the skeleton. Gorgonians and antipatharians are easier to sample than scleractinian (reef-building) corals, but they are also fragile and tend to lose tissue integrity upon collection.

For hard corals, we have to be incredibly picky in finding the perfect coral to sample – thin skeletal margins set higher than the surrounding reef so the manipulator jaws can effectively break skeleton and collect tissue. With a little practice and a discerning eye, we are becoming more and more efficient at collecting all kinds of benthic species, including the corals that make Cuban mesophotic reefs so magnificent and diverse.

Ultimately, we are interested in how reef populations across the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean are interacting with one another, particularly those in existing marine protected areas in U.S. and Cuban territories. With data describing genetic connectivity across regions, management strategies can be implemented and refined to protect valuable ecological resources and diverse mesophotic coral ecosystems.

Sampling our deepest Montastraea cavernosa found so far at 85 meters depth along he lower mesophotic wall. This colony was extremely brittle, which is thought to be a photoadaptive response to low light environments. Image courtesy of Cuba’s Twilight Zone Reefs and Their Regional Connectivity. Download larger version (jpg, 679 KB).

Using the ROV suction hose to collect fragments of Agaricia sp. off the top of the wall in the upper mesophotic zone at 50 meters depth. The vacuum prevents small pieces from falling out of reach once they break. Image courtesy of Cuba’s Twilight Zone Reefs and Their Regional Connectivity. Download larger version (jpg, 546 KB).