By Jeff Godfrey, University of Connecticut

March 27, 2016

Jeff Godfrey investigates a rock covered with encrusting fauna during a dive off of Gilbert Peninsula. Image courtesy of the Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 3.2 MB).

The story of advancements in science has, in part, been the story of the advancement of the tools and techniques used in research.

During the 1700s, materials that burned in air were said to contain phlogiston. The popular hypothesis at the time was that phlogiston was lost to the air during combustion, and this hypothesis persisted for over a hundred years. It was only with the advent of very accurate scales, and development of accurate and repeatable measuring techniques, that Antoine Lavoisier was able to demonstrate that combusted materials gained weight and thus disproved the faulty hypothesis. This consequently led to the development of the Law of Conservation of Matter. Today, Lavoisier is often named the father of modern chemistry and is an example of a scientist only being as good as his tools and techniques. A large part of a scientist’s time is spent developing the tool kit that they will need to make new discoveries.

The cold waters of Glacier Bay Nation Park's fjords require our divers to wear a dry suit. A dry suit has water tight seals at the wrist and neck as well as a water tight zipper that keep a small layer of air trapped in the suit as insulation. Our divers also wear gloves and neoprene hoods for additional insulation. Image courtesy of the Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 2.3 MB).

Diving is a tool that has been used by scientists to make observations and collect samples since 1844 when Henri Milne Edwards first used a diving helmet to collect samples in 26 feet of water off the coast of Sicily. Technological advances allowed refinement in equipment, but the surface supplied mode of diving available to scientists remained largely unchanged for the next hundred years. CK Tseng, using surface supplied diving equipment developed in Japan, became the first scientific diver at the Scripps Oceanographic Institute.

Surface supplied diving equipment requires a large surface support crew, is expensive, and requires a significant amount of training for both the diver and the support crew. This limited the number of scientists that could use diving as a tool to only a few that had the funding to acquire the equipment and the time for training. There was also the issue of the limited range. Scientists were attached to the surface by an umbilical, so they could only survey a limited area of the seafloor.

During our dive at Gilbert Peninsula, our divers had a visit from a sea lion. Image courtesy of the Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

The development of a Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus (SCUBA), named the Aqua-lung by Émile Gagnan and Jacques Cousteau, addressed all these problems. Because the Aqua-lung was relatively simple and reliable, scientific divers now had an inexpensive way to access aquatic environments. There was no longer a need for surface support, because a diver carried all of their life support with them and a diver’s range was limited only by the amount of breathing gas carried and not by the length of the umbilical.

While working in remote areas like Glacier Bay National Park, we need to bring our own compressor. Here Jeff Godfrey fills tanks between dives. Image courtesy of the Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 2.4 MB).

Early scientific divers made many significant discoveries using scuba, but the death of a University of California graduate student in 1953 highlighted the need for a structured training program to enable scientist to use this new tool safely and efficiently. In 1953, Conrad Limbaugh was appointed as the Marine Diving Specialist for Scripps and charged with developing a scientific diver training program. Today, many universities have scientific diver training programs that are based on the one developed by Limbaugh and some of the first recreational diver training courses were taught by people trained by Limbaugh.

In 1977, the American Academy of Underwater Sciences (AAUS) was organized in response to OSHA regulation of commercial diving. AAUS sets consensual standards for scientific diver training, equipment, and operations. A beginning scientific diver can expect to spend 100 hours in training before being granted a Scientific Diver Certification by their institution. This certification allows the use of scuba using air as a breathing gas while conducting underwater research.

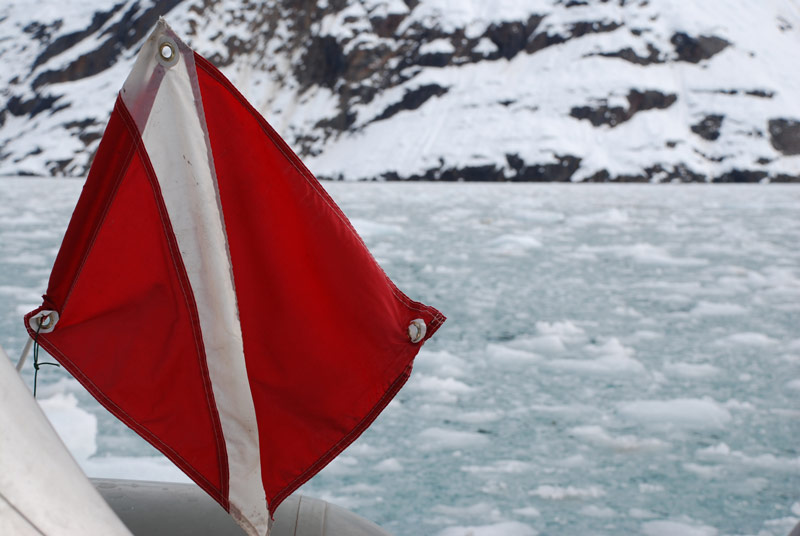

Diving in Glacier Bay National Park has presented some interesting challenges for maintaining safe scuba operations, including relocating dives due to heavy icepack, seen here close to Johns Hopkins Glacier. Image courtesy of the Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 3.5 MB).

The use of advanced diving modes like mixed gas diving or the use of closed circuit rebreathers requires additional training. With the use of these advanced modes of diving, scientists are now able to dive longer and deeper. Because of the time spent training, scientific divers have a much lower accident rate than commercial, military, or recreational divers. Today, scientists are diving to depths in excess of 400 feet and making significant discoveries about out our aquatic environments. As Lavoisier demonstrated more than 200 years ago, a scientist is only as good as his or her tools, and the time spent using those tools is invaluable in the effort to make new discoveries.