By Liz Baird, Chief of School and Lifelong Education, North Carolina Museum of Natural Science

September 3, 2016

Justin Fujii secures the full-size cups inside the middle compartment of the AUV Sentry. Image courtesy of Exploring Carolina Canyons expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 5.9 MB).

It is difficult to imagine the pressure deep in the ocean. Just as there is a change in air pressure when one goes up a mountain or an elevator in a tall building, the water pressure changes as one dives deeply in the ocean. Our equipment, such as the autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) Sentry or the CTD rosette, are built to withstand intense pressure. At the ocean’s surface, air pressure is about 14.7 pounds per square inch (or one atmosphere). On average, the pressure increases about one atmosphere for every 10 meters you dive.

Animals that swim down to great depths have special adaptations to deal with the changes in pressure. Some fish have swim bladders, which are special sacs filled with air. They can regulate how much air goes into the bladder, allowing them to control their buoyancy and move up and down through the water column.

Whales also swim to great depths but have a different strategy for dealing with the pressure change. While diving, they’re able to safely collapse their lungs, which prevents lung rupture and blocks gas exchange inside the lung. Instead of relying on their lungs as the source of oxygen, they rely on enhanced oxygen stores in their blood and muscle until they’re able to resurface and breathe in oxygen from the air.

Many fish that live in the deep sea don’t travel very far off the bottom, up into the water column, so they do not have to deal with these pressure changes. Because they are adapted to the deep-sea environment, the pressure inside their bodies is similar to the pressure in the outside environment. Generally, deep-sea fish don’t have swim bladders but instead have reduced muscle and tissue density, higher fat content, and minimal bone structures so their bodies are better able to withstand the pressures of the deep.

A fun way to demonstrate the change in pressure is to attach a Styrofoam cup to a piece of sampling equipment and send it down to the bottom of the ocean. As the cup descends, the air is squeezed out of the Styrofoam and the cup shrinks. The deeper it goes, the smaller it gets.

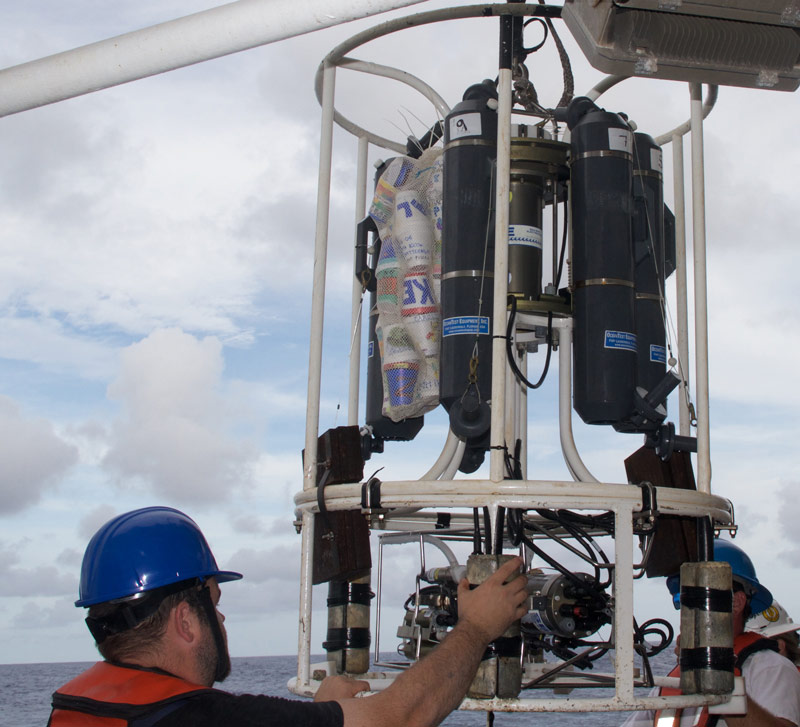

The mesh bag of cups is secured to the CTD rosette before being deployed to the deep sea. Image courtesy of Exploring Carolina Canyons expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 2.7 MB).

In anticipation of following along with this expedition, youth participating in the Junior Volunteer program at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, in Raleigh, North Carolina, and students from Millhopper Montessori School in Gainesville, Florida, decorated cups with permanent markers. Over the course of the expedition, additional cups were decorated by the scientists and ship’s crew.

To shrink the cups, we first stuffed a crumpled-up piece of paper into each cup, which keeps them from stacking into each other. We then placed them in a sturdy mesh bag and cinched it closed with zip ties. The bag was placed in the middle compartment of the AUV Sentry or attached to the CTD rosette and sent down into the depths of the ocean.

It is amazing to see the bag disappear into the sea bulging with cups, only to return with miniatures in their place. We find that our artwork looks much better when it has been shrunk!

We’re excited to use these cups to explain the pressure of the deep to the groups that decorated them!

Cups filled with paper prior to crushing. Image courtesy of Exploring Carolina Canyons expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 5.9 MB).

The cups after they have been sent down on the AUV Sentry. Image courtesy of Exploring Carolina Canyons expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 6 MB).

Cups from the Junior Volunteers at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and some of the science team after a dive. Image courtesy of Exploring Carolina Canyons expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 3.9 MB).

These cups from Millhopper Montessori School are beside an original cup showing the difference in size. Image courtesy of Exploring Carolina Canyons expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 5.5 MB).