By Dr. Elizabeth Shea, Curator of Mollusks, Delaware Museum of Natural History

While cephalopods are not one of the target species for this cruise, they are routinely found in the same benthic habitats we observe in the canyons. They are unintended subjects of the photos, but almost always elicit a laugh or a gasp or a cheer of “octopus!” when encountered. They are the look-at-me, photobombing, momentary scene-stealer in an otherwise serene benthic environment.

Cephalopods are encountered in all phases of the exploration. The midwater is the biggest biome on Earth, and photos of fast-moving cephalopods and fish are rare. But when the underwater cameras are rolling during their descent and ascent, cephalopods and their inky remnants are regularly (albeit rarely) found (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A mastigoteuthid squid in the water column. Midwater observations are especially difficult because animals are often way out in the distance and moving quickly. Image courtesy of Deep-Sea Coral survey, NMFS, WHOI 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 1.1 MB).

When a cephalopod comes onto the screen, we can learn a lot of fundamentals about it in an instant – not just location, size and depth, but also important behavioral characteristics. The downside of these snapshots is that they are frustratingly fleeting, and species-level identifications are difficult.

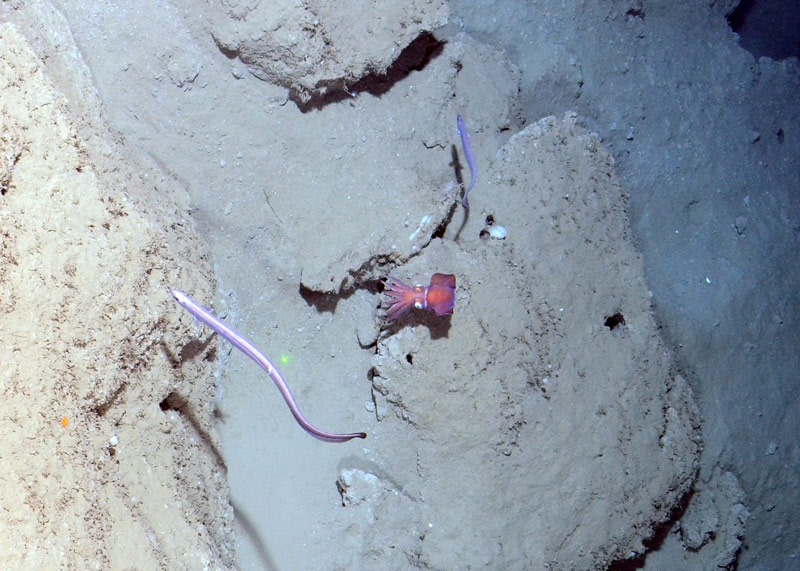

Cephalopods may be the only obvious animal on a sandy bottom, or they may be cryptic in the background, blending into the browns and greys of the seafloor. A first glance at many photographs reveals corals and sponges, but after zooming in, a small purple potato with eyes can be seen looking up at you - a sepiolid cephalopod! These cuttlefish relatives are often found at rest on the bottom with their arms tucked under their bodies and their prominent eyes watching the underwater world go by (Figure 2).

Figure 2: This Rossia sp. swims over the bottom using the large fins that extend along the length of the mantle (body). Image courtesy of Deep-Sea Coral survey, NMFS, WHOI 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

The most commonly encountered cephalopod on bottom is the large, incirrate octopod, Graneledone verrucosa. This octopod is easy to identify because it is big, purple, and has a mantle covered in prickly bumps. We may see this species out for a stroll (Figure 3), but we have also seen many of them tucked into the cracks and crevices of rocks, probably protecting batches of eggs.

Figure 3: Octopus! This Graneledone verrucosa is out for a stroll. Image courtesy of Deep-Sea Coral survey, NMFS, WHOI, ROPOS 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 280 KB).

This expedition will provide essential information for understanding the coral and sponge habitats and distribution in the Atlantic canyons. I’m excited to be a small part of that effort, and happy every time I hear the cheer, “octopus!”