By Chris Taylor, Research Ecologist - NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science

Avery Paxton, PhD Candidate - University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Institute of Marine Sciences

September 7, 2016

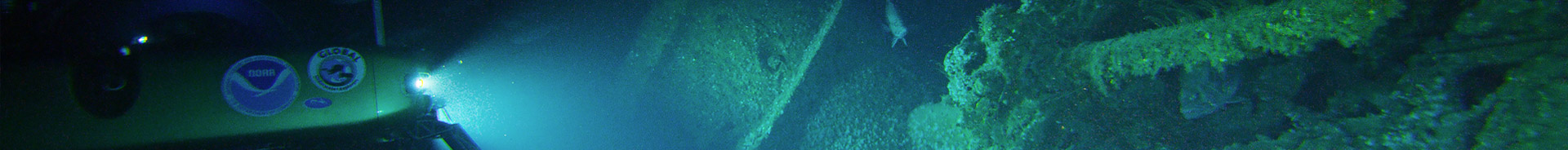

Light from the submersible reveals that fish occupy both the structure of the U-576 and the water column above. Image courtesy of John McCord, UNC Coastal Studies Institute - Battle of the Atlantic expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 7.8 MB).

As the submersible traversed the U-576 for the first time, large grouper and snapper held their posts, like sentinels of the now-quieted warship. These fish live on the U-576 because they require structure, like that provided by shipwrecks on the seafloor, for protection and food.

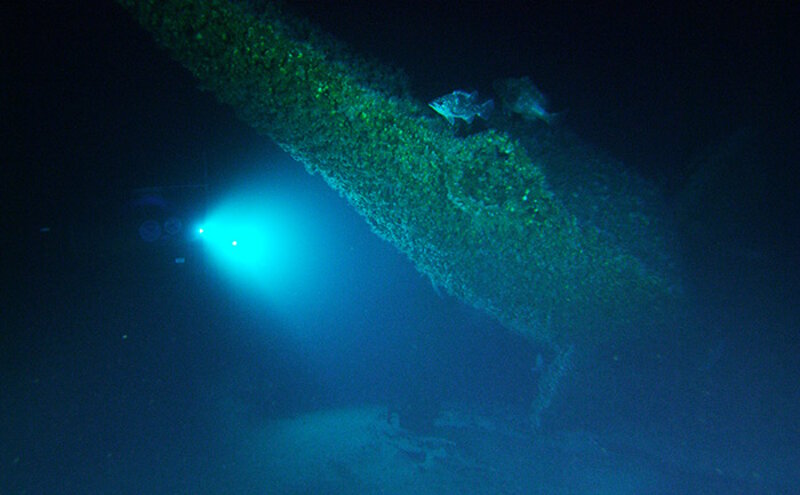

Different types of fish, including grouper (throughout) and conger eel (bottom center), rely on the U-576 for habitat. Image courtesy of John McCord, UNC Coastal Studies Institute - Battle of the Atlantic expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 461 KB).

Off the coast of North Carolina, thousands of shipwrecks speckle the seascape, dispersed among the natural, exposed bedrock that forms extensive reefs in both shallow and deep waters. These shipwrecks create reefs for fishes that our coastal fishing and diving communities depend on. However, we lack a full understanding of the distribution of these reef features and how they grow such valuable fishes.

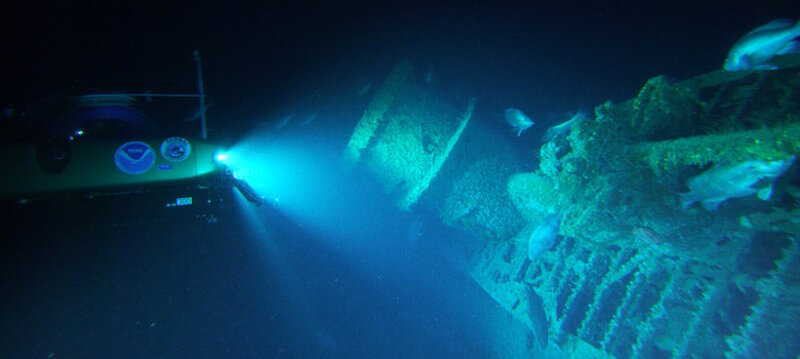

Grouper congregate around the conning tower of the U-576. The structure on the seafloor forms a reef that provides fish with protection and food. Image courtesy of John McCord, UNC Coastal Studies Institute - Battle of the Atlantic expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 290 KB).

To learn more about how fish use shipwrecks off our coast, we are using technologies similar to those harnessed to solve the mystery of the location and condition of the U-576. Our approach is built in stages and relies upon old and new technologies that give us images of increasing breadth, resolution, and detail. But with increasing detail comes cost.

“Eyes in the water” are the most expensive tools in our tool chest, whether it is “eyes” of divers, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), or the submersibles. For this mission, our “eyes” are submersibles outfitted with innovative technologies, such as video cameras and laser line scanners, that provide glimpses of how fish use reef structures on the seafloor. Video cameras record fish schooling around the reefs and those hiding in crevices. Laser-line scanners use light directed across the reef structure to build visual models of how fish are distributed around the reefs and also allow us to count fish and measure their size.

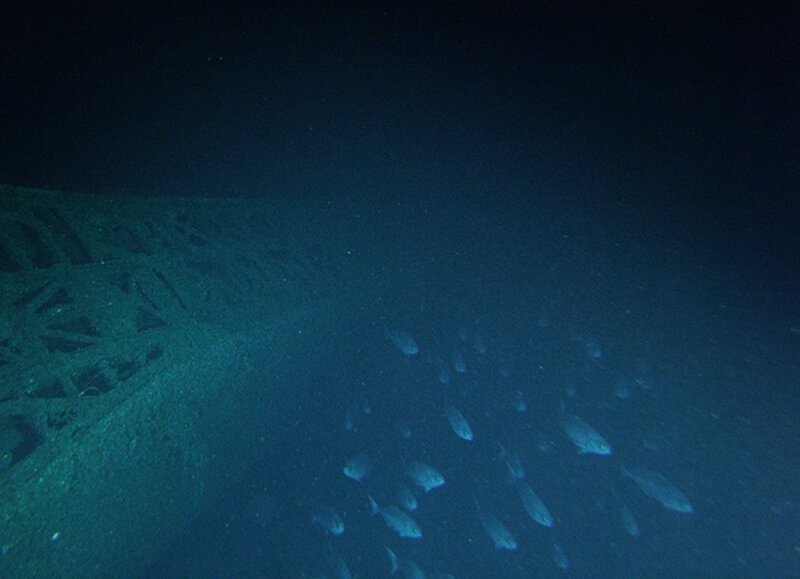

Lights from the submersible illuminate several different types of grouper on the stern of the U-576. Image courtesy of John McCord, UNC Coastal Studies Institute - Battle of the Atlantic expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 6.8 MB).

The images we have gathered of the two primary targets of the mission, U-576 and Bluefields, continue to surprise us. Many different types of fish concentrate around the shipwrecks. Some of these fish belong to a group of fish managed by the federal government because of their high value for fisheries, as well as their depleted numbers for many species. For example, snowy grouper, Warsaw grouper, and yellowedge grouper glide above the wreck structures and meander into internal spaces. Schools of snapper and jacks corral silvery baitfish. Invertebrates encrust the wreck structure, providing food for the reef-associated fishes. The shipwrecks are alive with marine life.

A school of silvery fish glides above the deck of the U-576. Image courtesy of John McCord, UNC Coastal Studies Institute - Battle of the Atlantic expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 6.0 MB).

Our approach during this mission is novel because it bridges the fields of archaeology and biology. Prior to this mission, reconstructing the history of shipwrecks (archaeology) and understanding how fish use wrecks as habitat (biology) were two distinct components, addressed with different efforts and separate tools. During this mission, we developed a new method, one where we use the same effort and tools to simultaneously gather archaeological and biological information on shipwrecks. The innovative methods we developed will help us continue to explore historical shipwrecks and natural rocky reefs in deep waters off North Carolina and the Atlantic Coast.