By Debi Blaney - NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

September 4, 2016

German U-boat U-576 and crew. “Submarine crews don’t have it easy earning their daily bread. It is the most uncomfortable and Spartan life, and the work is often very monotonous. But the sailor bears this with grim humor.” Hunt in the Atlantic by H. Busch. Image courtesy of Ed Caram Collection. Download larger version (jpg, 78 KB).

The German Navy was a force to be reckoned with during World War II (WWII). German submarines – or unterwasser boats (U-boats) – were on a mission to destroy merchant vessels carrying supplies to allied forces in order to hinder their war efforts. Aided by intelligence reports on the location, destination, and speed of merchant vessels, the U-boats would search the seas for victims.

Kapitӓnleutnant Hans-Dieter Heinicke, commander of the U-576 (left) speaking to military leadership. “The commander is the brains and eyes of the entire crew. He bears the sole responsibility and the full weight of the mission, the decisions, and the actions. He is the only one on the submarine who is aware of the big picture; the others only follow blindly and duty bound, performing tightly controlled tasks, whatever that task may be. The commander alone leads.” Hunt in the Atlantic by H. Busch. Image courtesy of Ed Caram Collection. Download image (jpg, 65 KB).

Sometimes they were organized into so-called “wolf packs” and hunted in North Atlantic waters in groups. Other times, in geographically spread out regions where wolf packs were not feasible, a U-boat would hunt by itself.

U-576 at sea. “The commander can completely rely on his crew and their ability to combat any imaginable situation. Every move has been rehearsed; every possible occurrence has been prepared for.” Hunt in the Atlantic by H. Busch. Image courtesy of Ed Caram Collection. Download larger version (jpg, 192 KB).

When a U-boat spotted a target, it was not uncommon to track enemy vessels for days as the sub called in reinforcements for a large, coordinated attack. Equipped with deck guns and torpedoes, the attack could happen from the surface or from underwater, depending on circumstances. If the U-boat was on the surface, crew might assess the damage they had inflicted visually, before diving back under water to remain protected from a counter attack.

Brief reports sent from the U-boats to their headquarters back on land gave account of their successes, measured in the amount of enemy tonnage they were able to send to the bottom of the ocean.

Crew of U-576 at watch in the conning tower. “The men of the gray boats came together from all areas of the Reich to form one colorful German whole, linked together and working in sync. Our crews are like the sword wielding brotherhoods of the Viking age.” Hunt in the Atlantic by H. Busch. Image courtesy of Ed Caram Collection. Download larger version (jpg, 3.0 MB).

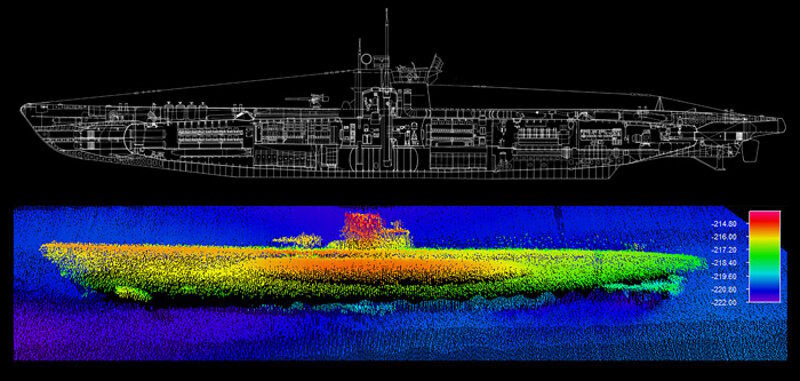

U-576 was a German U-boat built in 1940 and launched the following year under the command of Kapitӓnleutnant Hans-Dieter Heinicke. Heinicke and his 45-man crew went on four patrols as part of the seventh U-boat flotilla based in St. Nazaire, France, but they did not sink any enemy vessels during their first two patrols off the coasts of Russia, Ireland, and England. They did, however, have more success when they were sent across the Atlantic to hunt in the waters off the coast of North America starting in January 1942.

U-576 was part of the first wave of 16 U-boats dispatched to attack merchant ships near the Canadian and U.S. shores. In February 1942, on its third patrol, U-576 sunk its first ship, the 6,900-ton unescorted British freighter Empire Spring, 50 miles from Sable Island. On its fourth patrol in April of the same year, U-576 sank two more ships, the 5,000-ton American merchant vessel Pipestone County and the 1,300-ton Norwegian freighter Taborfell.

![U-576 crew members. “They [the crew] are chipper in a rough kind of way, satisfied with their lot, and proud of their work.” Hunt in the Atlantic by H. Busch. U-576 crew members. “They [the crew] are chipper in a rough kind of way, satisfied with their lot, and proud of their work.” Hunt in the Atlantic by H. Busch.](media/friends_800.jpg)

U-576 crew members. “They [the crew] are chipper in a rough kind of way, satisfied with their lot, and proud of their work.” Hunt in the Atlantic by H. Busch. Image courtesy of Ed Caram Collection. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

Reinhard Hardegen, recalls in his book On Combat Station! U-Boat Engagement Against England and America what it felt like to be a German U-boat commander at this time: “We were to sail to America as the first envoys to hit a good number of merchant ships in different harbors all at the same time. Those were our orders. As a U-boat commander I could not have dreamed of anything more exciting, it was new territory for me. We knew much was at play with this first attack on America; we had to get the first strike right. The stronger the hit was, the more effect it would have.” Hardegen’s orders included a battle call: “Hit them like you’re beating a drum. Attack on! Sink them! You mustn’t come home empty handed.” The resulting offensive became known as Operation Drumbeat (Operation Paukenschlag).

Diagram (top) and sonar image (below) of U-576. Image courtesy of NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 1.1 MB).

Many weeks at sea followed for the crew of the U-576 and other U-boats. While no personal details of individual sailors onboard U-576 are known, Harald Busch, another German U-boat commander, offers vivid descriptions of what life onboard a submarine during Operation Drumbeat was like in Hunt in the Atlantic: “The most striking thing when one is at sea for the first time on a war-experienced submarine is the sober realization of the difficulty of everyday life on board: flight alarms, submarine traps, pursuing destroyers, even torpedoes, weeks of bitter cold temperatures, and ongoing high seas. So many extreme efforts have to be made before a brief and simple war report can be dispatched mentioning even the most modest of successes. It’s difficult to conceive of the effort behind such a report”.

U-576 crew members posing with their wives. “We descended in the late afternoon and stayed under water as we all wanted to celebrate Christmas undisturbed. The big Christmas tree shone brightly in U-boat command. Other areas of the sub also donned smaller trees, lovingly decorated and lit by electric candles. The whole crew assembled in U-boat command and we celebrated our war Christmas together. Von Schrӧter played holiday tunes on his accordion, and we all sang together. After a short speech we all stood around the tree together, everyone lost in their own thoughts. We thought of our loved ones back at home.” On combat station! U-Boat engagement against England and America by R. Hardegen. Image courtesy of Ed Caram Collection. Download larger version (jpg, 1.8 MB).

Busch elaborates on the hardship of daily life on board, and on what kept the crew motivated: “The sailor likes to appear unburdened and happy, but as soft and contemplative as he may seem, he is also hard. He has to be. He has to survive the enormous forces of the sea, and not give in. Daily life on board is incredibly scarce. The lay person cannot imagine what it means to be out at sea in a submarine for weeks at a time and in enemy territory. There are days, sometimes weeks, where you hunt for prey without any success. For weeks at a time, the men don’t get a chance to step outside onto the conning tower to catch a glimpse of the sun and some air. Many of the technicians never even get to see the bridge. And everyone on the ship is on constant red alert.

U-576 at the dock. “Rarely have we left port with this much confidence, and the full trust of our Admiral. This time there were no flowers decorating the boat; instead little Christmas trees adorned the bridge.” On combat station! U-Boat engagement against England and America by R. Hardegen. Image courtesy of Ed Caram Collection. Download larger version (jpg, 112 KB).

“On board there is no place to be comfortable, stretch your legs, and relax from your strenuous shift, except perhaps the bunk bed, which you have to share with your mates. The work is monotonous and cramped; three times a day you get to wolf down your meal cowered in the tiniest of spaces, then to sleep on an ever soggy bunk bed…and soon it is time to report back to duty. There are no showers, no shaves, no getting out of your clothes for the entire time of the trip. But the sailors are proud of their boat and their commander, they are proud to achieve something, proud to play a part in the success. The crew and the commander of a boat form a sworn brotherhood that can even chase the devil out of hell.”

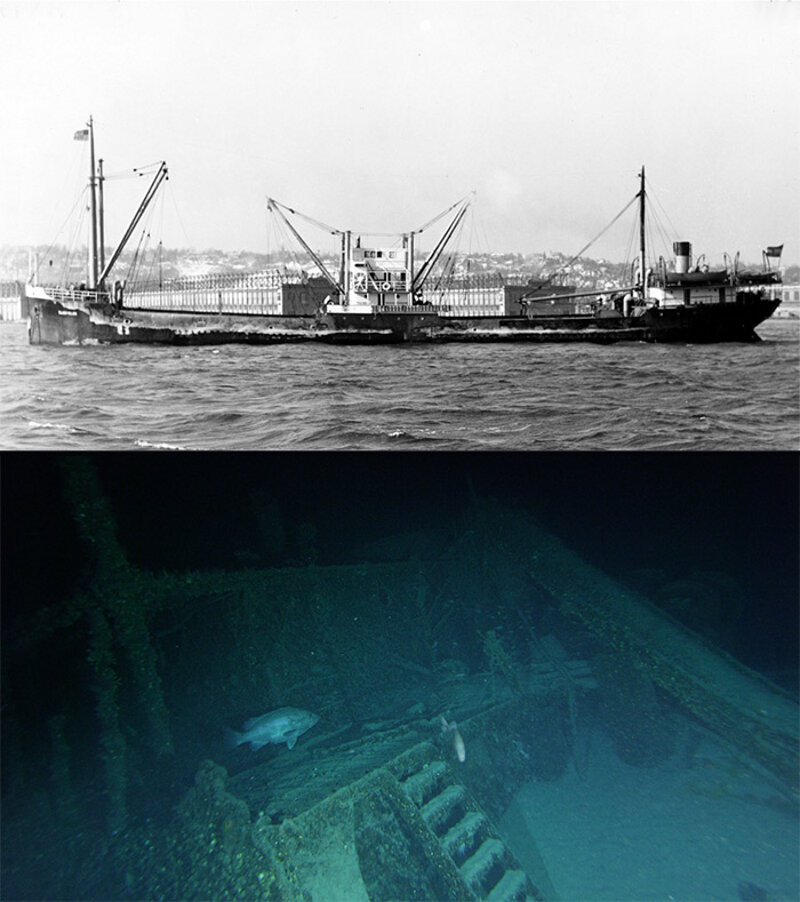

Merchant vessel Bluefields as it was configured near the time of the attack (top) and its wreck today (bottom). The right hand side of the ship is visible in the wreck image, showing the ladder leading from the main deck to the aft superstructure and the stern crane lying collapsed on the deck (diagonal structure visible on the top right). Photo courtesy of NARA and NOAA/Project Baseline taken by John McCord, UNC Coastal Studies Institute, respectively. Download larger version (jpg, 387 KB).

Concluding its fourth patrol, U-576 reached its home port in St. Lazare, France, in May 1942, after a long 49 days out at sea. A month later, in June 1942, U-576 left Europe again for American waters, headed to Cape Hatteras for its fifth and final war patrol with the mission to intercept allied merchant vessels off the coast of North Carolina. U-576 arrived off the U.S. coast in early July, hunting the Atlantic waters mostly by itself. During this time, the German U-boat supreme command received a report from U-576 stating: “In the sea area off Hatteras, successes have dropped considerably. This is due to a drop in traffic (formation of convoys) and increased defense measures.” (B.d.U. 1942b:30309a). The allies had begun effective convoy routing and anti-submarine warfare to mitigate threats from German U-boats.

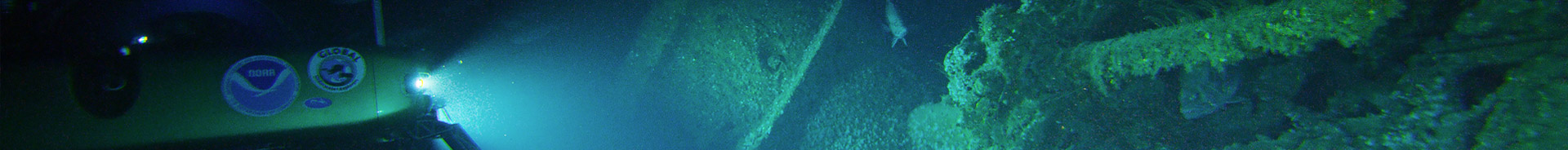

A submersible shines its lights on the wreck of U-576 lying on its starboard side, showing the submarine's conning tower and the deck gun in the foreground. Image courtesy of John McCord, UNC Coastal Studies Institute - Battle of the Atlantic expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 3.7 MB).

On July 13, 1942, U-576 reported to its headquarters an encounter with an enemy aircraft dropping depth charges, causing damage to its main ballast tank. After attempts to repair the damage, U-576 resumed hunting in shipping lanes close to shore. On July 15, the U-boat came across a merchant convoy (KS-520) consisting of 19 merchant vessels and five military escorts headed to Key West to pick up fuel from golf refineries. U-576 attacked the convoy south of Cape Hatteras and sank the merchant vessel Bluefields and damaged two others. An Allied counter attack including aircraft and escort vessels ensued, and minutes later, U-576 itself sank and the entire crew was lost.

More than 72 years later, on August 24, 2016, the U-576 wreckage was seen for the first time since it sank. Project members of the Battle in the Atlantic expedition are investigating the wreckage to assess the exact damage it sustained before sinking. Did U-576 flood and the crew drowned? Or did they instead suffocate locked inside the submarine? Are any of the hatches open, which may indicate an escape attempt by the crew as their boat was sinking? These and other questions remain of the U-boat’s final moments before it became forever a dark tomb.

Translations of excerpts from On combat station! U-Boat engagement against England and America and Hunt in the Atlantic by Debi Blaney.