By Brandi Carrier, Archaeologist - Bureau of Ocean Energy Management

September 2, 2016

For many reasons, the Battle of the Atlantic expedition is a project of profound importance. It provides an opportunity to explore approaches to battlefield archaeology in a maritime environment and across a six-month time span, and contributes to our understanding of how close World War II (WWII) came to U.S. shores and the ultimate sacrifice born by the merchant mariners defending them. In addition, the project will also demonstrate new technologies and methodologies for conducting archaeological documentation and investigation.

A video frame grab of the stern of U-576. The stern torpedo tube can be seen between the two rudders. Image courtesy of John McCord, UNC CSI - Battle of the Atlantic expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 3.8 MB).

But in perhaps its most understated contribution, the project also represents an ideal example of federal, state, private, non-profit, and international partners coming together to tell the story of a shared past. Under leadership by the United States’ federal ocean agencies, the Battle of the Atlantic expedition, as a historic preservation initiative, is exemplary of the national policy that is promoted under the National Historic Preservation Act.

The conning tower of U-576 as viewed from the mini-sub. Entry was gained to the U-boat through a watertight hatch located in the center of the conning tower. The attack periscope can be seen in the near the back of the tower. Image courtesy of Joe Hoyt, NOAA – Battle of the Atlantic expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 9.0 MB).

With the passing of The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (NHPA), Congress clearly communicated its intention that the federal government was to be a leader and full partner in historic preservation. The purposes of the NHPA are largely set out as national policy in section 2 of the preamble of the act: “It shall be the policy of the Federal Government, in cooperation with other nations and in partnership with the States, local governments, Indian tribes, and private organizations and individuals to…administer federally owned, administered, or controlled prehistoric and historic resources in a spirit of stewardship for the inspiration and benefit of present and future generations; [and] contribute to the preservation of non-federally owned prehistoric and historic resources and give maximum encouragement to organizations and individuals undertaking preservation by private means.” The KS-520 battlefield and the Bluefields and U-576 are certainly sites and resources worthy of this federal attention.

Archaeologist Brandi Carrier aboard the R/V Baseline Explorer participating in the Battle of the Atlantic expedition. Image courtesy of NOAA – Battle of the Atlantic expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 2.0 MB).

Moreover, the importance both of strong federal leadership as well as meaningful involvement of states, local governments, even international governments, and others in telling the shared human story cannot be understated. Archaeology and complimentary disciplines such as maritime history represent the joint telling of stories communicating our shared understanding of human history. An important component of this paradigm is providing public access for sharing in that past as well.

Archaeology isn't the domain only of scientists and specialists; according to Congress, the public can and should be invited to share in ownership and stewardship of these resources. Studying other cultures, and studying our own cultural past, brings us together as a global community and makes our ideological differences seem far less important.

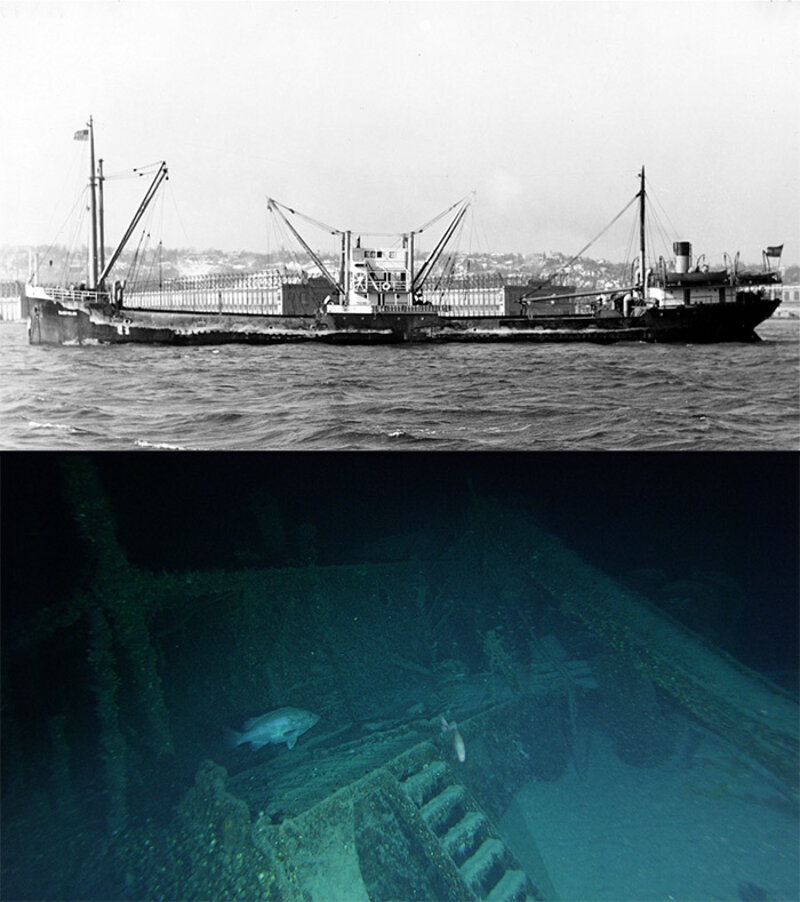

Merchant vessel Bluefields as it was configured near the time of the attack (top) and its wreck today (bottom). The right hand side of the ship is visible in the wreck image, showing the ladder leading from the main deck to the aft superstructure and the stern crane lying collapsed on the deck (diagonal structure visible on the top right). Photo courtesy of NARA and NOAA/Project Baseline taken by John McCord, UNC Coastal Studies Institute, respectively. Download larger version (jpg, 387 KB).

According to Winston Churchill, “history is written by the victors.” But the story of WWII is an international story, a world story. The newest partner in telling this shared story will be the German government. During the 2016 expedition, representatives of the German government will visit the site of the downed U-boat, its victim Bluefields, and the war graves of 45 sailors. The battlefield lies in U.S. federal waters, on submerged U.S. federal lands; the U-boat remains the property of the German government. This complex legal jurisdiction notwithstanding, the story is a shared one. It is fitting and just, then, that this shared story be told by all those who participated in it.

When we see the davits of Bluefields swung wide, devoid of the lifeboats that are clearly visible in earlier photos of her, we imagine what it may have been like to abandon a sinking, fire-ravaged ship, terrified, with a hulking U-boat nearby. When we read the after-action reports of the battle, and then document the hatches of U-576 locked down tight at the bottom of the sea, we remember that 45 sailors went to their deaths that fateful afternoon, and imagine their last thoughts before they realized their fates.

In these ways, we feel the gravity of the war, even now, nearly 75 years later. These experiences that we imagine, and the feelings that they provoke in us, aren’t national ones; they aren’t local ones either. These experiences and feelings are human ones. They are part of the human story we wrote together during WWII.