By Dr. Jennifer Questel and Caitlin Smoot, Zooplankton Researchers, University of Connecticut, University of Alaska Fairbanks

July 23, 2016

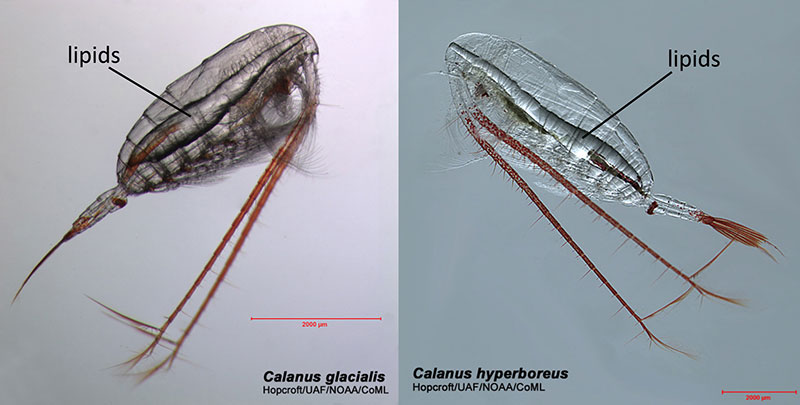

The two copepod species Calanus hyperboreus and Calanus glacialis prepare for the winter by storing lipids, as seen in the photos. Images courtesy of Russ Hopcroft, UAF, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (349 KB).

Zooplankton in the Arctic must deal with harsh winter conditions, including freezing temperatures, limited food availability, and the Polar Night. The Polar Night refers to the time of year when the Arctic experiences 24 hours of darkness each day. The region is also covered with sea ice during this time of year.

Due to the lack of sunlight, food (i.e., phytoplankton) becomes extremely limited during the Polar Night. Therefore, some groups of zooplankton, such as the copepods, have developed specialized adaptations to survive the winter when food is scarce.

The first adaptation to survive the winter is the ability to store energy in the form of lipids, or fats. We are currently experiencing 24 hours of daylight in the Arctic, a time known as the Midnight Sun. During this time of year, phytoplankton become plentiful, allowing zooplankton to build up large lipid reserves by feeding on phytoplankton. This is essential to their over-winter survival. When food is limited during the Polar Night, zooplankton will utilize their lipid stores to survive until the next summer.

The Clione is a small gastropod that, along with the copepods, is also a member of the zooplankton community. This individual was brought up in the plankton nets during this expedition. Image courtesy of Microcosm Film, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (88 KB).

This jar of plankton and sea water was collected by the plankton net. The red copepods are apparent under the light. Image courtesy of Caitlin Bailey, GFOE, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (3.6 MB).

In addition to serving as an energy reserve, the lipid stores also allow zooplankton to carry out diapause, another adaptation to living in the harsh Arctic environment. Diapause is when zooplankton descend to deep, cold water and reduce their metabolic rates during the Polar Night. In addition to serving as an energy source, lipids allow the zooplankton to remain neutrally buoyant (stay at depth). By reducing metabolic rates during diapause, zooplankton can make their lipid stores last through the winter.

As winter ends, environmental cues tell the zooplankton when it is time to come out of diapause, increase their metabolic rates, and ascend to the surface. Before ascending from depth, some species of zooplankton will also use their lipid reserves to begin egg production. Other species wait until they have returned to the surface during the phytoplankton bloom to carry out egg production.

Lipid storage and diapause allow zooplankton species to survive the harsh Arctic winter conditions. The timing of the start and end of diapause, as well as egg production, allows different species of zooplankton to reduce direct competition for food resources and increase their offspring’s chance of survival.

Calanus hyperboreus and Calanus glacialis are two of the dominant copepod species we are observing in samples collected by the plankton nets during this expedition. These two copepod species both go into diapause during the Polar Night. Calanus hyperboreus begins egg production at depth, while Calanus glacialis can wait to produce eggs until the next Midnight Sun phytoplankton bloom.

We are observing phytoplankton in the guts of these copepods, as well as the accumulation of lipids in their bodies. This shows that they are preparing for the upcoming Polar Night. Both of these species are very abundant in the Arctic, and their lipids make them an energetically rich food source for upper trophic levels, such as fish, seabirds, and whales.

The unique adaptations of these copepods not only allow them to survive the winter, but also make them an important link in the Arctic food web.

Caitlin Smoot and Dr. Jennifer Questel hose down the plankton net after a successful deployment and recovery. Image courtesy of Caitlin Bailey, GFOE, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (3.4 MB).