By Kate Segarra, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Expedition Coordinator

July 12, 2016

See a timelapse of the Healy breaking through the ice floe and hear the rumbling sounds as steel meets ice. Video courtesy of Caitlin Bailey, GFOE, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (mp4, 31.8 MB).

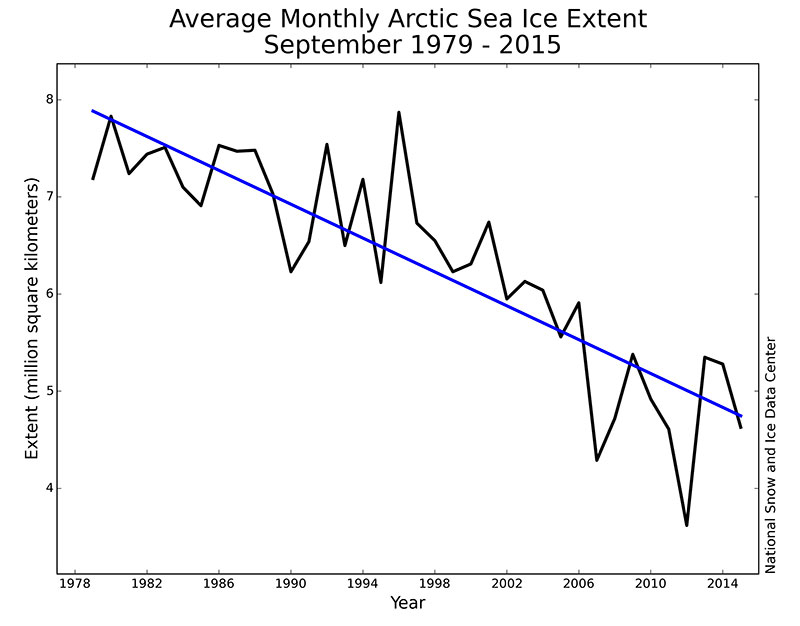

In the months leading up to this expedition, news was circulated that 2016 is on track to set a new minimum for sea ice in the Arctic. We were all concerned about these predictions and the implications for both the ecology of the Chukchi Sea as well as the impacts on our science mission. Sea ice in the Arctic reaches a minimum at the end of the melting season in September. The lowest Arctic sea ice minimum occurred in 2012. According to the National Snow and Ice Data Center, September sea ice extent declined 13.4 percent per decade between 1979 and 2015. However, low ice coverage does not mean no ice coverage and the Chukchi Sea is currently a mosaic of ice floes and open water.

The thick fogs masks the vastness of the ice floe, making it difficult to navigate. Image courtesy of Caitlin Bailey, GFOE, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (3.3 MB).

We’d crossed the Arctic Circle only a day before when the Healy started hitting some very thick ice. The U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy breaks ice by using an “ice knife” on the bow that was specially designed to cut into and break ice, which then allows the ice to pass down each side of the ship. In thinner, first-year ice, ice breaking for this cutter is a snap. However, ice thick enough to endure at least one melting season (called multi-year ice) puts up more of a fight.

In ice this thick, the going is slow. Very slow. The ship uses the ice knife and also rafts up onto the ice, which momentarily holds the weight of the ship before giving way to the tons of steel above it. The Healy then backs up a ship-length or two and uses this cleared space to build up momentum and ram the ice again. It’s an impressive process to see from the bow, and perhaps even more impressive to hear as the ice scrapes along the hull, creaking and groaning as it breaks.

This graph shows the overall trend of decreasing Arctic sea ice over the past 30 years. Graph courtesy of the National Snow and Ice Data Center. Download larger version (jpg, 406 KB).

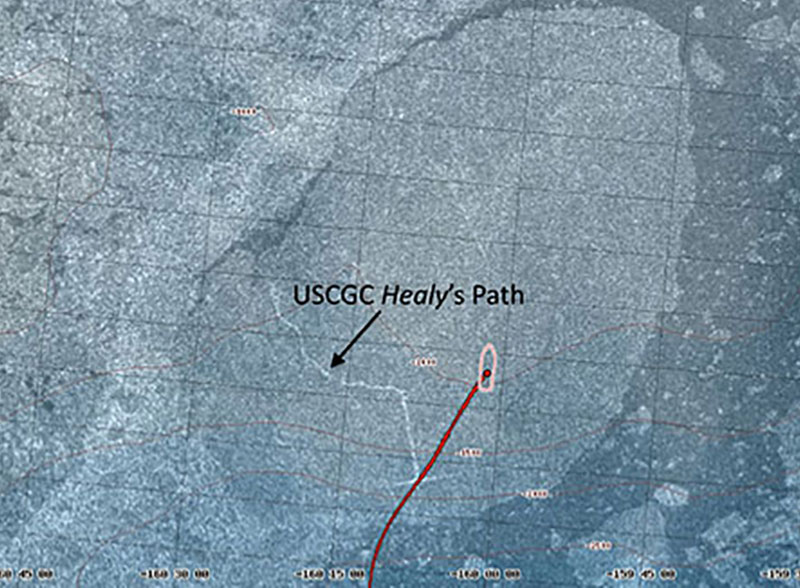

This satellite image shows the path that the USCGC Healy carved through the ice floe. While the GPS image showed our heading going north, the ice floe continued to spin without our knowing, keeping us within its icy grasp. Image courtesy of The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (jpg, 451 KB).

On Saturday (July 9) evening, the entire ship rattled and shook as the Healy cut through multi-year ice that was over 4 meters (14 feet) thick in some places. We were not sure how long it would take us to travel the 20 or so nautical miles to our first station given the ice coverage, but it was expected we’d be at our first station around noon the next day. We all went to sleep lulled by sounds of ice meeting steel and excited by the thought that after days of transit we would finally be collecting samples!

In the science lab, there is a white board which displays the plan of the day. This board is known as the ‘Board of Lies,’ thus called because things at sea don’t always go according to plan. Our plan of the day on Monday changed from having a look around the Arctic benthos with the remotely operated vehicle to waiting.

The Healy was slowly breaking its way through a giant ice floe. Visibility was poor and the satellite ice imagery the crew relies upon for navigation is only updated once a day. To complicate matters, the ice floe was being pushed and rotated by the Beaufort Gyre, a wind-driven, clockwise current in the Arctic Ocean. At the pace the Healy was breaking ice (less than one mile per hour) we were drifting with the floe faster than we were traveling through it.

We spent that day and the next two days plowing through a terrain of ice and scattered melt ponds. It is now Tuesday, July 12 and we are still in the ice floe. Our escape is imminent – we can see the open water just a few miles ahead of us!

The thickness of the ice is apparent as the Healy continues to try to plow through the large floe. Image courtesy of Caitlin Bailey, GFOE, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (3.5 MB).

While we are frustrated by the delay this ice has caused us, the past few days have been full of wonder and beauty. We have seen polar bears and seals (see Kate Stafford’s log here). It also afforded the expedition’s first opportunity for some ice operations (a log entry about ice-based research is coming soon). Being ice-bound for four days has also built camaraderie amongst the science party. Our ice floe feels like another planet inhabited by only polar bears, seals, and the 141 of us aboard the Healy.