By Dr. Kate Segarra, Expedition Coordinator, NOAA, Bureau for Ocean Energy Management

Caitlin Bailey, Web Coordinator, NOAA, Global Foundation for Ocean Exploration

August 7, 2016

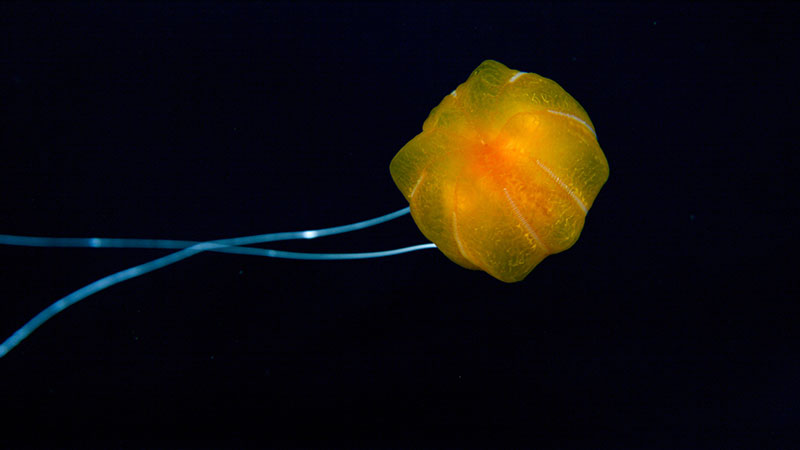

This image of Mr. Pumpkin in the water column was taken by the Global Explorer ROV. It is important to image any undescribed species in its own habitat. Image courtesy of The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands, Oceaneering-DSSI. Download larger version (1.6 MB).

During this expedition, the science party has collected multiple ctenophores that may represent new species. Of course new is a bit of a misnomer – these graceful animals were around long before human existence. The correct taxonomic term is ‘undescribed’. To understand exactly how a scientist goes about describing a new species, we spoke with jellyfish expert Dr. Dhugal Lindsay of JAMSTEC about the process he will use to attempt to describe the orange ctenophore we have been affectionately calling “Mr. Pumpkin”. This process applies to jellies (siphonophores, ctenophores, scyphozoans, etc.), however, one might follow a different method for other kinds of organisms.

During the Hidden Ocean 2005 expedition, multiple observations of these orange ctenophores were made with the ROV. It was hypothesized at that time that these creatures represented a new species. Based on appearance, Mr. Pumpkin was assumed to be a member of the genus Aulacoctena. However, the species remains undescribed. Thanks to the high-definition video footage and multiple specimens collected with the Global Explorer ROV, the science party now has much more information to support a description.

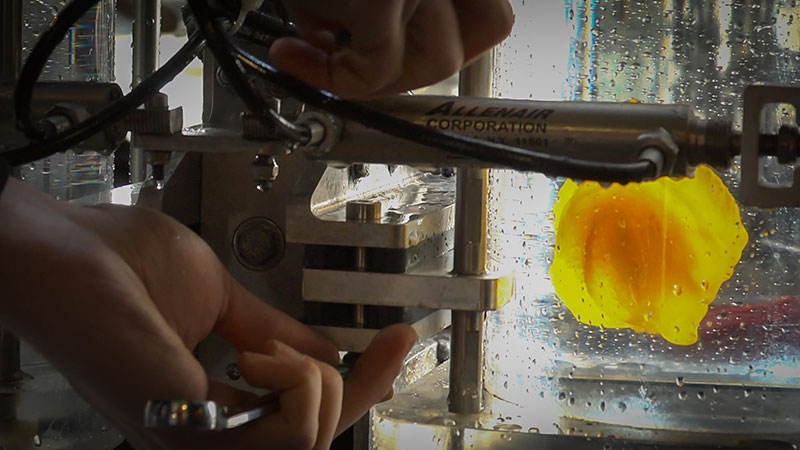

Specimens of Mr. Pumpkin collected by the Global Explorer ROV allow scientists to look at the ctenophores’ structure and take DNA samples. Image courtesy of Caitlin Bailey, GFOE, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (jpg, 383 KB).

Dr. Dhugal Lindsay gets a closer look at Mr. Pumpkin. Image courtesy of Kate Segarra, NOAA, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

The first step of the description process often starts where all modern-day searches start – Google. If Dr. Lindsay did not already have prior knowledge of the taxa he would search for images of described species that look similar to Mr. Pumpkin. If an organism with some resemblance is found, the next step would be to search for the species in the World Register of Marine Species (WORMS; marinespecies.org), which, according to Dr. Lindsay, is the authority on the taxonomy of marine organisms. The WORMS entry will contain the citation for the original species description publication. Locating the original description of an organism is critical. If Mr. Pumpkin’s morphology differs from the species described, then the search continues with another image of another ctenophore. As one might guess, there is a lot of trial and error associated with this image-searching phase. As an added challenge, the original description might have been published anytime between the present day and 1760, when the first ctenophore was described. Thus, Dr. Lindsay will be sifting through manuscripts and texts in multiple languages published over hundreds of years to determine whether or not Mr. Pumpkin is indeed ‘new’.

If and when Dr. Lindsay has exhausted his literature search, he will prepare a species description paper of his own. This paper will describe the external and internal structure of the animal and place it within a larger taxonomic framework of ctenophore subgroups. Along with this paper, he will also submit a holotype, or representative specimen, to a museum for archiving along with photographs to supplement the preserved organism.

Of the 150 or so described ctenophore species, only around 30 of these species’ DNA sequences are available. Surprisingly, genetic barcoding is not required to describe a new jelly species. Nonetheless, Dr. Lindsay will sequence Mr. Pumpkin’s DNA and submit it to the GenBank database. Future researchers will be able to compare the DNA of unknown specimens with the sequences of this and other known ctenophores. Not only will these genetic comparisons allow for more taxonomic precision, it will save a heap of time should their sequences land a hit.

Dr. Lindsay is keeping mum about what he will be naming this new species. For now, we’ll stick with Mr. Pumpkin. The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands expedition has truly been a voyage of exploration and discovery! Who knows what other secrets the Chukchi holds? Now that science operations are over and we’re transiting back to Seward, we will have to wait until next time.

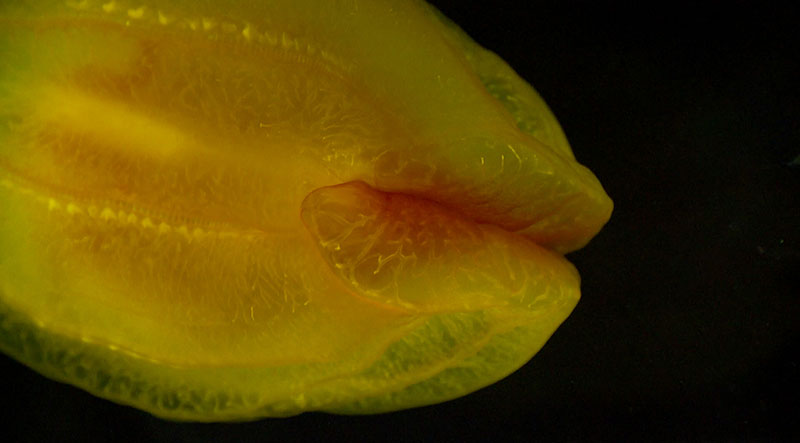

One of Mr. Pumpkin’s most noticeable features is its protruding 'lips.' Image courtesy of Caitlin Bailey, GFOE, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (523 KB).