By Russ Hopcroft, Chief Scientist, Institute of Marine Science, University of Alaska Fairbanks

August 26, 2016

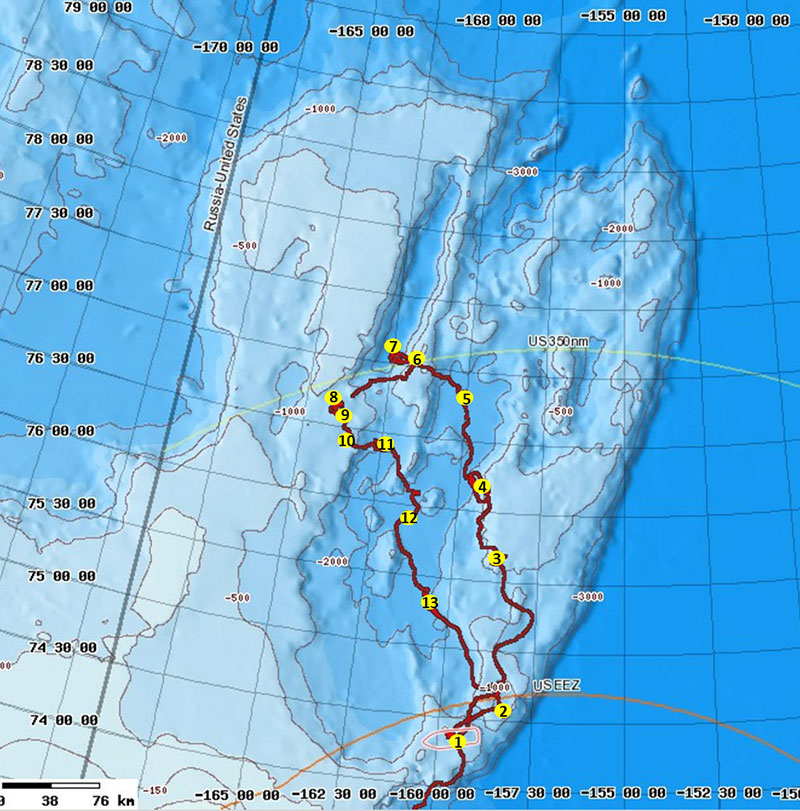

This map displays all 13 stations visited and sampled in the Chukchi Borderlands during The Hidden Ocean 2016 expedition. Image courtesy of Katrin Iken, UAF, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (363 KB).

The Hidden Ocean 2016 cruise followed the legacy of our prior expeditions by assessing the biodiversity within the Arctic’s three major realms - the sea ice, the water column, and the seafloor. For 40 days, our teams of scientists, students, technicians, remotely operated vehicle (ROV) pilots, and media professionals worked aboard the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter (USCGC) Healy to conduct exploration of the Chukchi Borderlands. In all, we visited 13 stations covering poorly known areas of the Northwind Ridge, Northwest Abyssal Plain, and Chukchi Plateau between 73-77°N latitude.

We used a combination of traditional collecting tools, along with underwater microscopes, genetic sequencing, and an ROV to act as our eyes and hands in the ocean’s depths. We made observations of unexplored habitats and captured undescribed species, in a locale that is currently undergoing profound change due to warming temperatures and sea ice loss.

The USCGC Healy sits close to an ice floe at Station 7 while members of the media team take video and photos. Image courtesy of Caitlin Bailey, GFOE, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (jpg, 2.3 MB).

A curious juvenile walrus checks out the ship during an ROV dive. Image courtesy of Croy Carlin, STARC, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (jpg, 952 KB).

To cover the full spectrum of ecosystem services, a major expedition such as the Hidden Ocean can be broken down into a number of specialized teams, all of which worked tirelessly and around the clock as needed.

Our sea ice team was really a jack-of-all-trades sequencing lab that not only looked at the life within the ice, but also the single-celled life floating in the water column and within the seafloor sediments. They focused on the single-celled plants and animals, bacteria, archaea, and viruses by counting them under the microscope and preparing them for genetic sequencing once we return to shore. In addition to sampling the sea ice itself, they sampled from the ship’s seawater intake, the CTD (conductivity, temperature, depth), the plankton net, the box cores, and even the ROV collection box.

The air-breathing animals that make the Arctic their home were censused by teams of observers on the ship’s bridge. One team counted and identified seabirds, finding that birds were abundant during our transits to and from the ice, but became rare once ice-cover became thick. The other team watched for marine mammals, from the great whales to ice seals, walruses, and polar bears. They had the unique ability to make all science stop by announcing they spotted a bear, whereupon everyone scrambled for their cameras.

The water column team contained the largest collections of scientists. It had a subgroup that was responsible for the Healy’s CTD package that determined the basic properties of the water, and for controlling the closure of up to 24 bottles used to collect seawater from distinct depths for more involved chemical (i.e., nutrients) or biological (i.e., plant pigments, bacterial counts) measurements. To this CTD package we attached two different underwater microscopes to create detailed image profiles of particles and zooplankton organisms in the water column that might reveal hot spots of life (as well as to cross-compare the two instruments).

Dr. Dhugal Lindsay (middle) and Dr. Russ Hopcroft (right) identify water column species while Joe Caba (left) pilots the ROV Global Explorer. Image courtesy of Yui Takagi, JAMSTEC, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (jpg, 2.1 MB).

An anemone anchors itself to a shell. This was sampled by the ROV Global Explorer during a benthic dive. Image courtesy of Microcosm Film, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (jpg, 786 KB).

In addition to the station CTD work, continuous chemical measurements of the seawater while underway built a reference frame for the hydrology of the study area and for the water column and seafloor organisms living within. A spring-loaded multinet was used to collect the smaller zooplankton (mostly small crustaceans), carving the water column up into as many as nine layers. It also towed a small net mounted to its side that was used to sort living animals to build a genetic library of Arctic zooplankton species.

The centerpiece of the pelagic team was Deep-Sea System’s ROV Global Explorer that allowed us to search for rarer zooplankton and collect up to 16 of them during a single dive. The ROV was equipped with Ultra High Definition (UHD) video, a standard that contained nine times more pixel information than the camera we had used in 2005. This improved resolution allowed us to identify the larger zooplankton to species from images, generally without the need to collect them, and focus on species that have yet to be described.

During this expedition, our focus became deep-sea jellyfish, especially the comb jellies (ctenophores). The comb jellies contain the zooplankton’s most fragile species, making them difficult, if not impossible, to collect with plankton nets. During this expedition, we collected six species needing to be described by science and given proper names. It is notable that we observed most of these same species from the ROV during our 2005 expedition, but were unable to collect them for proper description.

The benthic team consisted of the second-largest group of scientists, again with sub-groups. The box corer team used their half-ton “cookie cutter” to bring back quarter square meter sediment samples to describe the properties of the seafloor and assess the smaller organisms living within it. The beam trawl team dragged the seafloor to collect the more robust invertebrates and fish that lived on top of the seafloor.

The snailfish is a common benthic fish species found in the Chukchi Borderlands. This was sampled by the ROV Global Explorer during a benthic dive. Image courtesy of Microcosm Film, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (jpg, 221 KB).

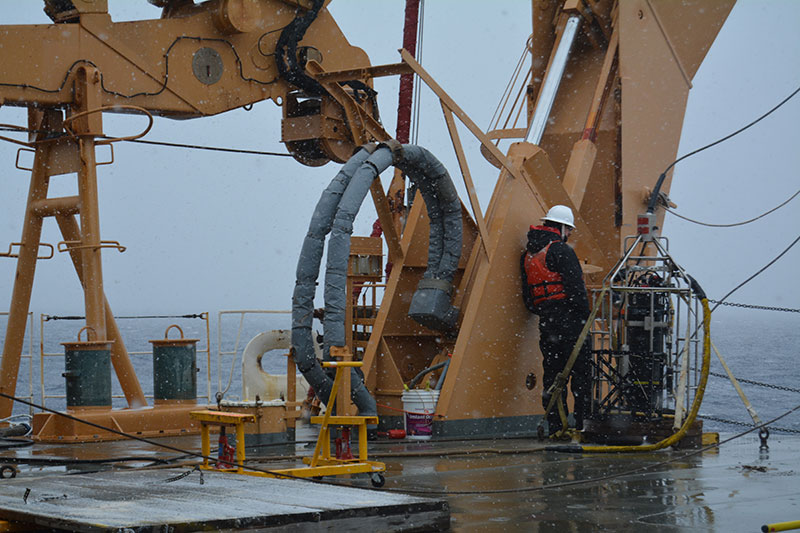

Snow in July was a novel experience for many members of both the science team and Healy crew. Image courtesy of Irina Zhulay, Arctic University of Norway, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (jpg, 786 KB).

Finally, the benthic team also used the ROV to develop an overview of the diverse habitats within the study area as well as observe and collect the larger and more dispersed animals living on the seafloor. These habitats ranged from richer communities on the shallow ridges to sparse communities on the plain of the Northwind Basin. One highlight was the observation of pockmarks created by past gas seepage, which now form shallow depressions (about 50 meters deeper than surrounding areas) in the seafloor that turned out to harbor unique seafloor communities. The team also found high abundances of some species (e.g., some bristle worms) that were first described from the region in 2005. More work is ahead of the benthic team to identify all the collected species and understand possible new species, new distribution records, and the respective influences of the Atlantic and Pacific waters that surround the Chukchi Borderlands.

Our final expedition component, and its last scientific task, involved the retrieval and redeployment of an oceanographic mooring on the Chukchi shelf that measured a suite of physical, chemical, and biological parameters for the past year. It is through instruments such as these that we learned about the broader seasonal patterns in the Chukchi region, how they vary from year-to-year, and to what extent longer-term cycles or trends occur. The biggest challenge in ice-covered waters is to find what was put in a year before – there was much rejoicing when the two primary strings of instruments rose to the surface upon sending out a release command via acoustics!

Unlike many scientific expeditions, we had a significant contingent of media professionals from three major sources, plus a teacher-at-sea. The NOAA correspondent focused on daily logs, while the Ocean Geographic team chronicled our adventures, and the Microcosm team focused on footage to build a documentary on the small and microscopic creatures that inhabit the oceans. The web resources from NOAA, and preliminary trailers from the other teams, suggest our adventures will continue to be released to the public or the classroom over the next six months to two years.

Seeing the Arctic "fogbow" is a unique experience that adds even more beauty to an already wondrous ecosystem. Image courtesy of Caitlin Bailey, GFOE, The Hidden Ocean 2016: Chukchi Borderlands. Download larger version (429 KB).