By Brian Cousin - Florida Atlantic University — Harbor Branch

August 26, 2015

The Mohawk remotely operated vehicle is launched onto Pulley Ridge. During the four-hour dive, we came across several grouper pits populated by a variety of fish species including the invasive (and unwelcome) lionfish, Pterois volitans. Video credit: Coral Ecosystem Connectivity 2015 Expedition. Download (mp4, 8.4 MB).

For this mission log, we’re focusing in on some of the smaller fish of Pulley Ridge. In past years, we’ve discussed groupers, which are charismatic and do amazing things like dig burrows 10 meters across and a meter deep by mouth and are often curious enough about our remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to come in close to the camera. However, a great number of smaller fish species are also present on Pulley Ridge and just as important to its biodiversity and how it functions.

Lt. Heather Moe, of the National Marine Fisheries Service’s Southeast Fisheries Science Center, (foreground) identifies fish species on a monitor during remotely operated vehicle dives and enters the information on a special keyboard that is connected to the database. In the background, graduate student Jana Ash enters benthic and invertebrate data using the blue-lit keyboard. Image courtesy of Brian Cousin, FAU Harbor Branch. Download larger version (jpg, 434 KB).

To adequately survey these fish, the ROV transects across the bottom are “low and slow.” Being a little closer to the bottom and taking a bit more time to transect allows the scientists to document and identify more of the smaller fish that tend to be cryptic, i.e., harder to spot because of their size and more likely to hide deeper among the rocks and corals.

A school of cardinal fish, Apogon sp., among the green alga Anadyomene menziesii on Pulley Ridge. Image courtesy of Coral Ecosystem Connectivity 2015 Expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 559 KB).

A great thing about the grouper burrows or pits is that they attract hundreds of small fish and are like oases in the desert. Each pit is a diverse community with all the inhabitants sharing mutual protection provided by the terrain and the presence of a large predator (the grouper).

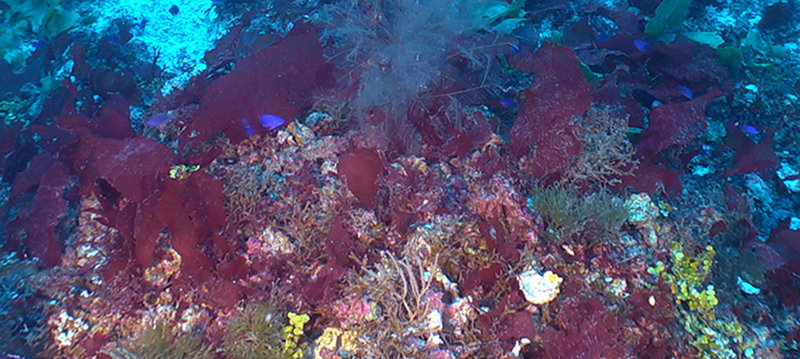

The purple reeffish, Chromis scotti, on a mesophotic coral reef. Pulley Ridge is home to the deepest photosynthetic coral communities off the continental United States. Image courtesy of Coral Ecosystem Connectivity 2015 Expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 580 KB).

Among the indigenous fish species on Pulley Ridge is an unwelcome intruder – the lionfish. The lionfish is a Pacific species that has spread throughout the Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean, and western Atlantic. They appear to have no fear of any fish species, and the local species haven’t yet recognized the lionfish as a threat or as food. The lionfish have moved into the grouper pits in large numbers to take advantage of the local ‘food supply.’ Pulley Ridge is a Habitat Area of Particular Concern and is protected from fishing impacts, but not invasive species.

Documenting the diversity of fish species on Pulley Ridge will help us better understand how this ecosystem functions. In addition to understanding how the ecosystem functions, this study is trying to better understand how Pulley Ridge may be connected genetically, ecologically, and oceanographically to ecosystems downstream such as the Dry Tortugas and Florida Keys. Helping understand how these ecosystems are connected will help us better protect them for future generations.