By Hans Van Tilburg, Ph.D., Maritime Archaeologist and Western Pacific Region Maritime Heritage Coordinator, NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries Maritime Heritage Program

September 28, 2015

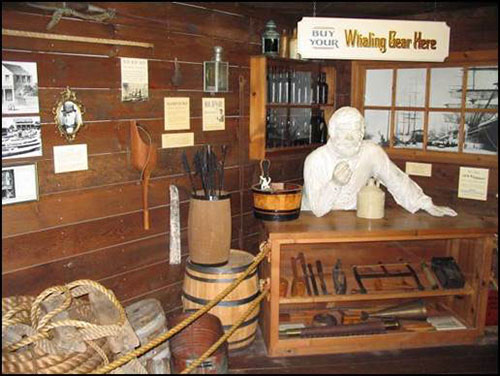

Display from Hawaii Maritime Heritage Center of a whaling-era merchant shop. Image courtesy of NOAA/ONMS/Hans Van Tilburg. Download larger version (jpg, 52 KB).

One of the things that I find the most interesting about the 1871 whaling fleet disaster in the Arctic is the fact that a substantial proportion, some 500 or more of the whalers involved, were Kanaka, a term associated with Hawaiian laborers (Kānaka maoli) and sometimes more broadly with Pacific Islanders during the 19th and early 20th centuries. We should note that this term was often used in a derogatory fashion at that time.

What was the impetus for thousands of young men taking up a dangerous and remote profession in unfamiliar waters? What was their experience on board the foreign vessels like?

It would be hard to overestimate the impacts of the whaling industry in Hawai‘i. The whalers brought a demand for services and provisions and sailors that would influence economic and agricultural practices across the islands. The increase in visits by seasonally transient vessels began in 1819 and reached a peak of more than 700 ships annually in the mid-1840s.

Photograph of Captain George Gilley, the only known native Hawaiian whaling captain. While Captain Gilly was not recorded as aboard any of the whaling ships involved in the 1871 disaster, he was the captain of the Hawaiian-registered whaling Brig William H. Allen, which was similarly lost, crushed in the ice, nearby off Barrow, in 1878. Image from Lebo, S., 2006. Native Hawaiian Seamen's Accounts of the 1876 Arctic Whaling Disaster and the 1877 Massacre of Alaskan Natives from Cape Prince of Wales. Download larger version (jpg,177 KB).

Most of the Big Five companies that later came to dominate the economic landscape of Hawai‘i’s plantation era got their start in the provisioning business. Ranches proliferated across the islands in response to the demand for beef. Ranching is still a way of life in Hawai‘i.

Hawaiians were, of course, familiar with whales. Open-ocean whaling was not a traditional practice, though beached whales were processed for food, and whale-tooth necklaces were an important symbol of rank. It was the combination of boom in whaling activities and the redistribution and consequent privatization of land enacted in 1848 (known as the great Mahele) that had a devastating effect on society. Tax and rent money was now demanded for what had once been common property. Seamanship and a sense of adventure, and curiosity for distant lands, were likely components of the decision to go on board the western whalers, but the harsh demands of an implanted cash economy cannot be overlooked.

Hawaiian sailors were known for their seamanship and swimming abilities and made desirable recruits for the whaling captains, so much so that the Hawaiian government began to regulate this recruitment and passed laws requiring bonds to ensure the sailors’ return to the islands as early as the 1830s. The demographic decline due to foreign diseases (an additional import of the early western whalers) made it all the more important to ensure the return of local sailors to Hawai‘i. Nonetheless, the role of Kānaka maoli in the American whaling fleet continued to increase. By 1871, Kanaka sailors made up almost half of the entire whaling crews in Alaska.

It may be possible to grasp the outlines of this story as an outsider, but there is an obvious need for a Native Hawaiian voice and perspective in order to understand the experience of these journeys and the hardships and discoveries made on board these ships. Some of the translations from the large archive of Native Hawaiian newspapers have revealed portions of these stories. One of these is the narrative of an 18-year-old Hawaiian sailor, Charles Edward Kealoha, and his voyage to the Arctic in 1876. Thanks to the Education through Cultural and Historical Organizations Partnership, a selection from Kealoha’s narrative has been made into a dramatization and is accessible at: http://www.echospace.org/articles/133/sections/199.html.

It is also worth noting here that there were a number of other relevant links between the 1871 abandonment and other important Arctic whaling events. Five of the ships lost in the 1871 disaster were of Hawaiian-registry (Comet, Julian, Kohola, Paiea, and Victoria II); one vessel from Hawaii was included in the rescue fleet (Arctic); and the survivors were taken back to Honolulu by the rescue fleet. Two other Hawaiian-registered vessels were documented as lost in the survey area off the Seahorse Islands, the Bark Hae Hawaii in 1868, and the Arctic (which was part of the 1871 rescue fleet) in 1876. In the 1876 disaster, off Point Barrow, the Desmond, W.A. Farnsworth, and the William H. Allen (Captain Gilley’s ship) were all vessels registered in Hawaii.

It has also been suggested by a number of sources that one of the reasons why there were an unexpectedly large number of vessels in the Arctic whaling fleet sailing under the flag of the Kingdom of Hawaii in the mid to late 19th Century was likely linked to the exploits of the Confederate Sea Raider Shenandoah. Near the end of the Civil War, the Shenandoah was fitted out by the Confederacy to target Yankee whaling ships and other merchant vessels. Having learned about the Sea Raider taking and burning a number of whaling ships early in it epic circumnavigation to find and destroy the whaling ships that were helping to support the economy of the North, ship owners were re-registering their whaling ships in Hawaii, as the Kingdom of Hawaii had declared its neutrality.

The Shenandoah was not generally taking and sinking vessels other than those registered in the U.S. (particularly from New Bedford and the other whaling ports in New England). While this was not a guarantee that the Confederate ship would not take and burn a vessel if it believed the Hawaiian registry was a “flag of convenience,” many of these newly registered Hawaiian whaling ships avoided this fate.

All told, the Shenandoah took 39 vessels on its campaign of destruction and this represented, like the 1871 abandonment, one of the contributory factors in the demise of American whaling. But the Shenandoah, as they say, is another story...