By Bradley W. Barr, Ph.D., NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries Maritime Heritage Program, Co-Principal Investigator and Chief Scientist

September 18, 2015

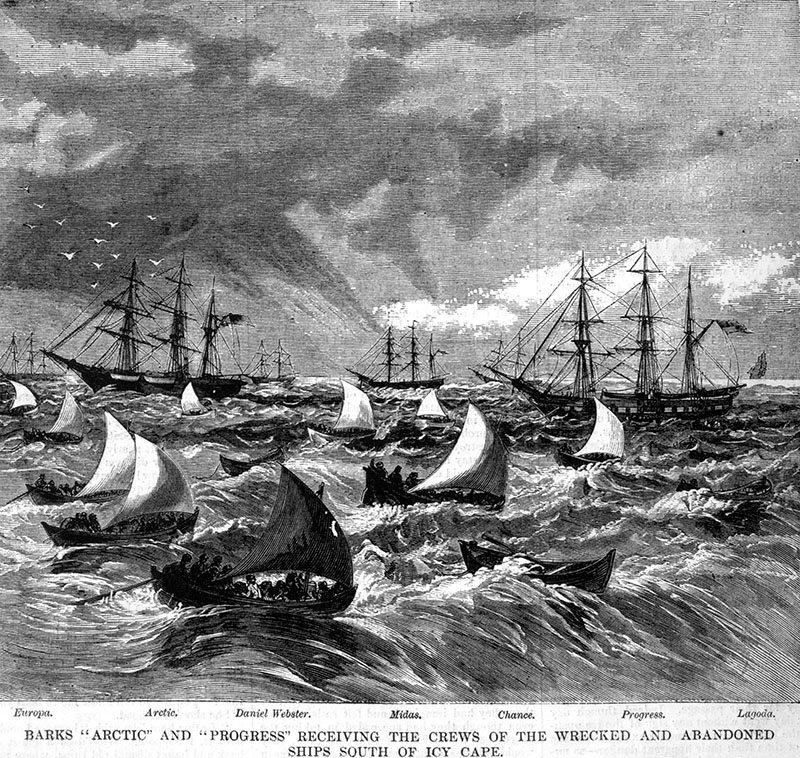

Barks “Arctic” and “Progress” receiving the crews of the wrecked and abandoned ships south of icy cape. Scanned images from original Harper’s Weekly, Robert Schwemmer Maritime Library. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

On this day, 144 years ago, the rescue fleet was beginning its journey back to Honolulu, having taken aboard the 1,219 survivors of who had successfully navigated the ice-choked and stormy waters along the Chukchi sea coast to safety. The rescue of all 1,219 officers, crew, and families aboard the abandoned ships was something of a vindication of the captains’ decision to attempt this perilous journey, but this was a most difficult decision to make.

Captains of any ship do not abandon their vessels except as a last resort, only when lives hang in the balance. And in 1871, these whaling captains were no exception.

The ice had their ships firmly in its grasp, slowly and relentlessly crushing the hulls and pushing the vessels toward the shore. As it was September, and the end of the whaling season in the western Arctic, they had taken as many whales as they were likely to (although there were reports of whales still being taken as the ice closed in on the fleet), and most had had moderately successful seasons with many casks of whale oil in their holds and a great deal of whalebone.

The long baleen of the Bowhead was also a valuable commodity, used for the manufacture of consumer items like umbrellas and corsets. Whaling ships during this “golden age of whaling” in the mid to late 19th Century routinely went to sea for up to three years, and some of the vessels in this 1871 fleet would have been heavily laden with the fruits of their labors over these years at sea...perhaps intending to head for home, to New Bedford or New London, after taking a few more whales at the end of this season to add to their bounty.

After the abandonment in 1871, it was estimated that the total economic loss to the whaling industry from this disaster was approximately $1,600,000, which translates – depending on how this is calculated – to between $28.8 million to $3.62 billion in 2014 dollars. This was a staggering loss to the industry, particularly to the whaling port of New Bedford where a significant number of these ships were home-ported. This event is widely attributed as being a contributory factor in the ultimate demise, around 1914, of the American whale fishery.

The captains knew full well they would be held accountable for this loss, but also knew they risked the lives of their officers, crews, and families onboard if they did not launch their whaleboats, one last time, and attempt the journey south to the rescue fleet.

Perhaps even more daunting, however, was the loss of their homes and possessions. These ships, for the long whaling voyages, were the places they lived and worked. They were, for some of the captains, the place where their families resided. In some cases, the ships where their children were born, raised, and grew into the next generation of whaling captains. To be forced to even consider abandoning their homes must have been a deeply troubling decision to contemplate.

Having visited many ports on these whaling voyages, and traded for many items of great economic and personal value along the way, these ships were laden with the personal mementos of the places they visited. The small whaleboats they would be relying on to carry them to safety would have already been loaded with the provisions necessary to sustain them until they could reach the rescue fleet (or for whatever might lie ahead), and so there would be little room for anything that was not essential for survival.

They abandoned their ships, most already sinking from the ravages of ice and storm, with only what they could carry, knowing what they were giving up, but holding on to the hope that rescue meant the possibility that there would be other voyages and other ships to call “home.”