By Bradley W. Barr, Ph.D., NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries Maritime Heritage Program, Co-Principal Investigator and Chief Scientist

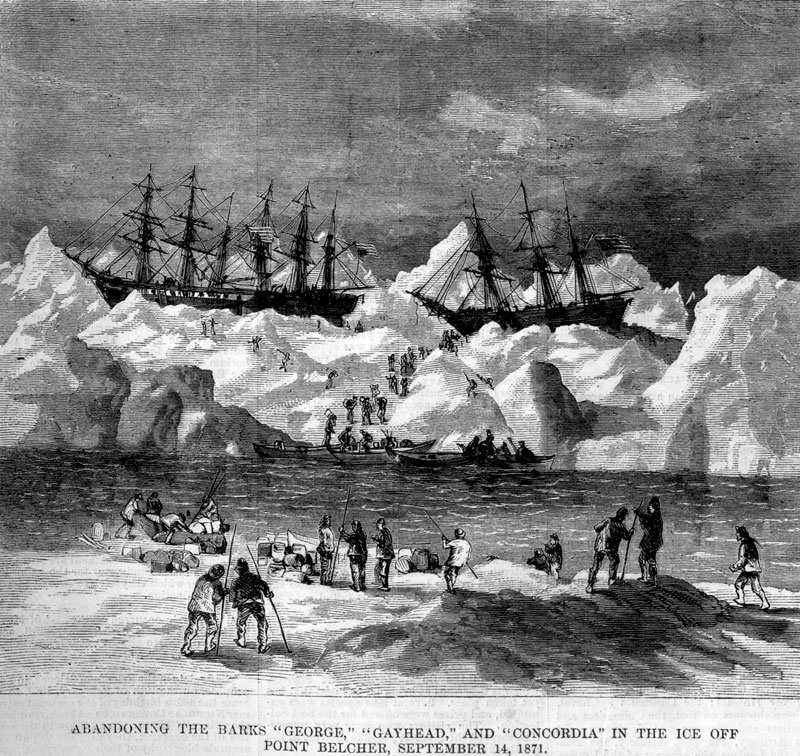

Abandonment of the whalers in the Arctic Ocean, September 1871, including the George, Gayhead, and Concordia. Scanned from the original Harper’s Weekly 1871, courtesy of Robert Schwemmer Maritime Library. Download larger version (jpg, 2.3 MB).

For more than a decade, the NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries’ Maritime Heritage Program (MHP) has been pursuing an initiative involving the very rich history and heritage of whaling in the Western Arctic. As the place where American whaling met its demise in the early 20th Century, the Western Arctic is a very significant place in the global whaling heritage landscape, with epic stories of the exploits of Americans engaged in this enterprise.

As the first truly global industry, a critically important driver of the U.S. economy in the late 18th through the 19th Centuries, and also an industry that had great influence over the early diplomacy of the U.S., whaling is something we as a society should better understand and appreciate for the many contributions it has made to our collective history. Whale oil lit the world at a time when urban crime was rampant in our cities, it provided jobs and economic development opportunities, and in some cases, like in the Hawaiian Islands, was the impetus for many aspects of social change that had a profound effect on the history of these ports of call that served the industry. While our perception of whaling today is somewhat different, in the 19th Century, Yankee whaling was central to the emerging global hegemony of the U.S. in the century that followed.

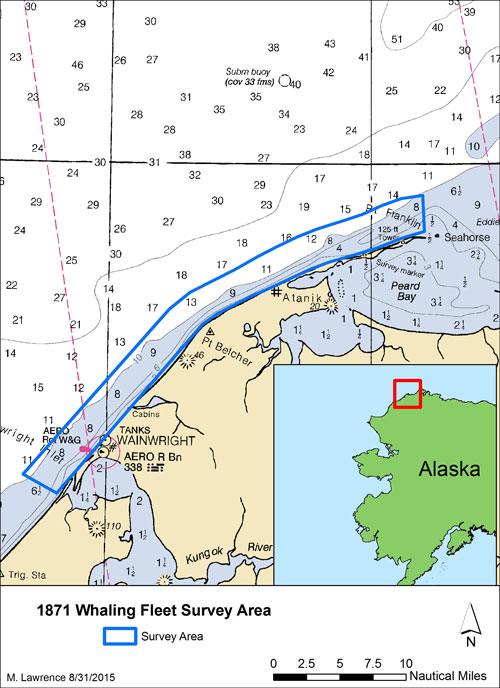

This map shows the area that was surveyed during the Search for the Lost Whaling Fleets expedition. Image courtesy of M. Lawrence/NOAA. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

In collaboration with the NOAA Office of Coast Survey and the Alaska Region of the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, we are heading to the nearshore waters of the Chukchi Sea, near Wainwright, Alaska, to comprehensively map a particularly important place in this Western Arctic landscape. In this place, in 1871 and 1876, around 50 whaling ships were abandoned and lost. Throughout the time whaling was taking place in the Western Arctic, from 1848 to around 1914, approximately 80 whalers were documented as lost in this “Graveyard of the Arctic.”

Until today, the area has been largely unexplored, insufficiently mapped, and our knowledge of what remains of these shipwrecked whalers in this important area is limited to only historical accounts.

Supported by, and with the active participation of, experts in seabed mapping from Edge Tech (an international leader in underwater mapping technology development), Hypack (developer of seabed mapping survey software used around the world), and Applanix (which has supplied critical elements of the mapping systems), we are expanding our knowledge of what remains, contributing to writing the final chapter of this story of whaling in the Western Arctic.

The overall goal of this mission is to search for what remains of the more than 80 whaling ships abandoned and lost in the area between Wainwright Inlet and the Seahorse Islands in the coastal waters of the Chukchi Sea. Using the 50-foot charter vessel R/V Ukpik, home-ported in Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, as the survey platform, the mission team is conducting a remote sensing survey using a number of state-of-the-art acoustic and magnetic mapping systems.

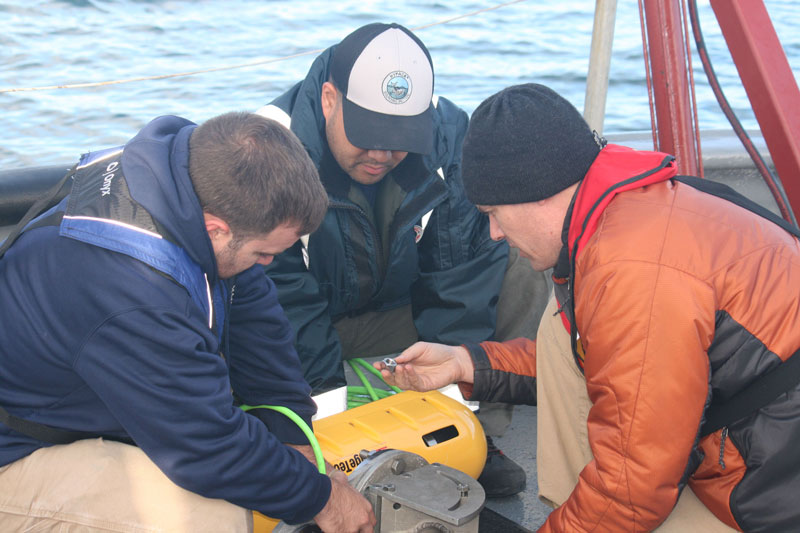

Evan Martizal, Vitad Pradith, and Matthew Lawrence ready the bowmounted swath bathymetry and sidescan sonar sensor for deployment. Image courtesy of NOAA/ONMS/Brad Barr. Download larger version (jpg, 2.6 MB).

The R/V Ukpik will depart Prudhoe Bay, Alaska on August 10 or 11, 2015, with a mission team of four and two captains (needed to conduct 24-hour operations throughout the cruise), and will arrive at survey area on August 11, immediately commencing mapping operations. Mapping operations involve navigating along pre-identified parallel lines in the targeted areas off the coast of these barrier islands, essentially like “mowing the grass.”

State-of-the-art mapping systems are being used to collect the needed data, including an Edge Tech 6205 Swath Bathymetry and Side Scan Sonar System, especially suited to mapping in the shallow waters along the Arctic coast (generously loaned to the mission by Edge Tech), enhanced with Applanix advanced motion sensors and GPS geo-location technology.

We are also using a very technologically-sophisticated marine magnetometry system – the first time such a system will be deployed by the NOAA Maritime Heritage Program, and, to our knowledge, in the Arctic. The system, called a “gradiometer” (two magnetometers towed horizontally), collects at-sea data integrated with information on the ambient changes in the Earth’s magnetic field collected by a base station magnetometer installed on the beach nearby). This mapping is targeted at identifying ferrous (iron) metal objects and components from these ships both on the surface and buried deeper into the seabed. As the mapping data is being acquired, it will be reviewed and analyzed by the mission team to identify “targets” that may be shipwreck sites.

Mapping operations will continue until August 19, when the vessel will return to Barrow to refuel, re-provision, and exchange personnel and equipment for the second period of operations.

Brad Barr readies the drop camera system for deployment. Image courtesy of NOAA/ONMS/Hans Van Tilburg. Download larger version (jpg, 4 MB).

The focus of the second leg of the cruise is to revisit potential targets identified in the previous mapping cruise. A towed side scan sonar system – an Edge Tech 4125 side scan sonar loaned to the mission from NOAA Office of Coast Survey – will be deployed to acquire higher-resolution acoustic images of the targets.

If this higher-resolution imagery suggests that a target may be wreckage, a drop camera system, purpose-built for this mission, will be drifted over these targets to collect high-resolution video documentation of these sites.

At the conclusion of the second leg on August 26, the R/V Ukpik will stop in Barrow to disembark a portion of the mission team and equipment. The vessel will then return to Prudhoe Bay. After the mission has been completed, we will develop both technical reports and summaries of the research findings for public distribution on the web, for presentations to the local North Slope communities and at various professional conferences and workshops, and for publications in relevant journals.

What happened in this historically significant place should be remembered. It is often said that if we forget the lessons of history, we are doomed to repeat it. Whaling in the Western Arctic was focused on a search for oil, something happening in a different context today, and the implications of that search offered many lessons that may help us, as a society, make informed decisions about what is happening now.

The climate of the Arctic in the 19th Century may not have been changing as rapidly, but whaling there opened up new economic opportunities as well as created challenges for sustainable resources use and conservation. This exploration provides an opportunity to fill in some of the gaps in our knowledge of this important story of American maritime heritage, raise awareness of this history and what it can teach us, and remind us of these lessons we have already learned and can benefit from in the future.