By Tony Saecier - ROV Pilot, Oceaneering

July 27, 2015

At times my job is hard work, like when installing all the parts of the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) system onto the vessel so we can do a job. Other times my job can be easy, like when the ship is moving from one location to another and I can just hang out for a while. The most consistent thing about this job, though, is that it's always interesting.

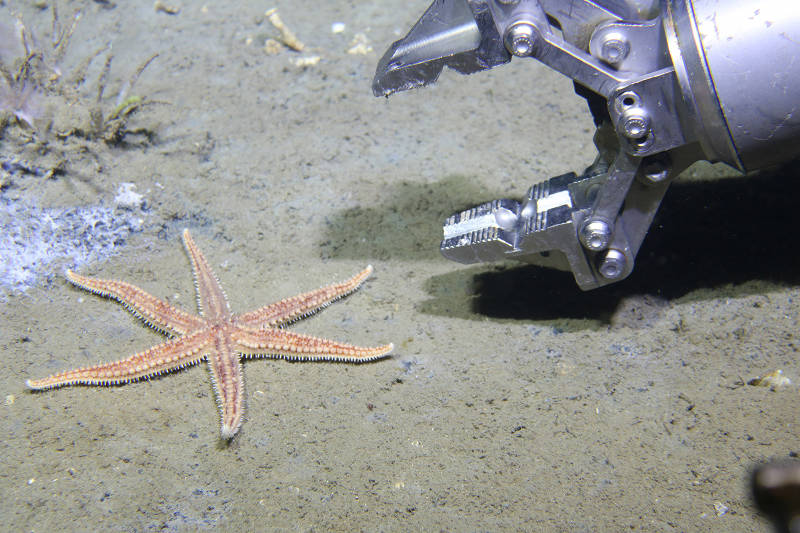

The ROV manipulator moving in to collect a seastar from the ocean bottom. Image courtesy of NOAA Bioluminescence and Vision on the Deep Seafloor 2015. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

The ROV crew is up and checking things out to make sure the ROV is in good running order every morning before the dive. We have to be sure because once we get into the water, there is no turning back.

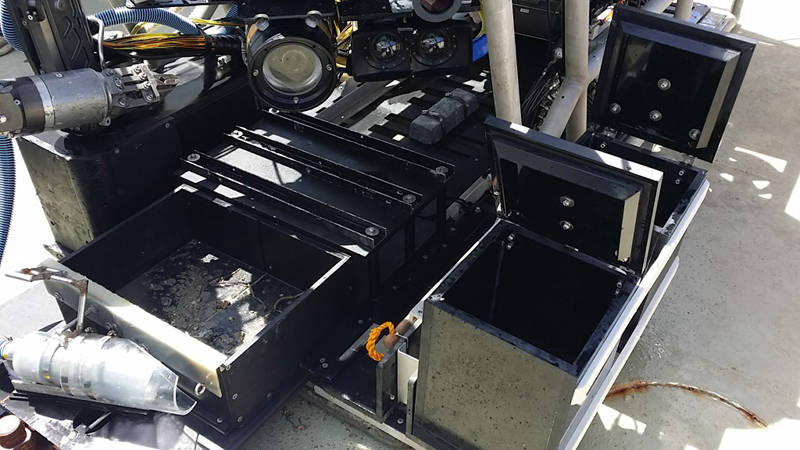

What the ROV looks like once it has hit the deck and the scientists descend upon it to collect all of the samples recovered from bottom. Image courtesy of NOAA Bioluminescence and Vision on the Deep Seafloor 2015. Download larger version (jpg, 552 KB).

Things are certainly a challenge at the bottom of the ocean with a device you are up to 3,000 meters away from. Bypassing the challenges of getting the ROV off the boat and to the bottom, we have to find both a target set of creatures the scientists need.

So as we begin our hunt for certain species, we are looking for any targets on the sonar that could be rocks or hard surfaces where life gathers. We may or may not find something nearby that fits this description, so we hover as close to bottom as possible to see if there is anything worth looking at along the seafloor.

While this may sound simple, it gets to be complicated when the extremely fine silt that collects over time on the bottom can be stirred up very easily. The questions usually come in sets of "Can we get closer to bottom?" which is immediately followed by "Where did all that dirt come from?".

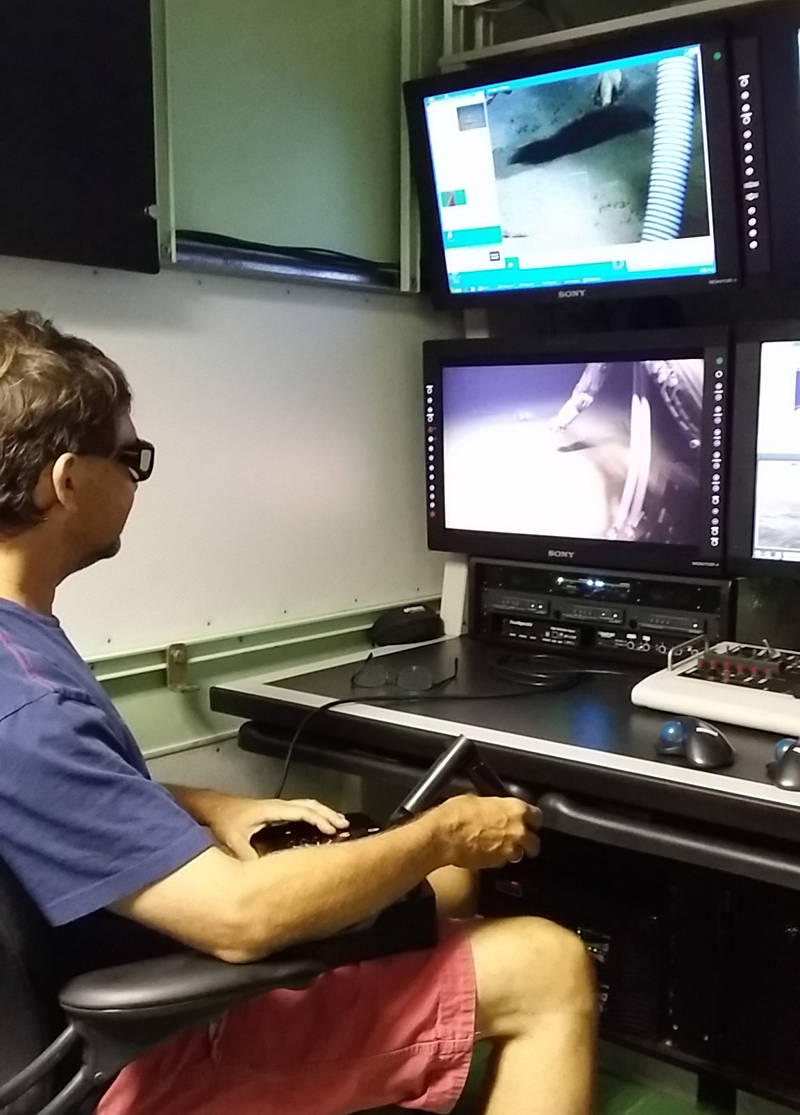

Sonke practicing using the manipulator to collect a sample and deposit it into the bio box. Image courtesy of NOAA Bioluminescence and Vision on the Deep Seafloor 2015. Download larger version (jpg, 283 KB).

Once we come upon an item that seems interesting to the scientists, they speak amongst themselves in what sounds like Martian languages to a non-scientist for just long enough that they don’t realize they forgot to tell you to stop the ROV. At this time they shout out to stop and look at something that's just going out of the frame of the camera. Immediately, reverse thrust is applied and all the silt that was trailing behind (think of a car driving on a dirt road) is pushed in front of the ROV and you have to wait (and pray) for the ocean currents to pull the dirt away so you can see what sparked the interest in the first place.

Once the ROV is stationary and the item of interest is in the camera frame, we can really get some excellent photos and video and usually even collect a sample to bring up. A lot of these things don’t get collected very often, so there is no really good information on how to do it.

The scientists can usually tell you a name for the animal that sounds like it has 147 letters in it, but I have learned over the last couple weeks that this generally doesn't help with collections at all. Things that were supposed to be "pretty mellow" have swum away like The Flash. Things that are "pretty tough" have fallen to pieces. Things that are just going to "break right off" have fought back like The Hulk.

All in all though, this is a first for a lot of the things we are doing, especially so for doing it with an ROV where we are collecting fragile samples and sea life with the same robotic arm that we also use to crush rocks when necessary. It takes some finesse, creativity, and no small amount of sheer, dumb luck. The scientists give the best advice they can and we all learn at the same time from there. So far we have made it work and had a very interesting time doing so. Every failure is a learning experience so the next time we know how to do it better. Each day is an improvement over the last and that’s all we can really ask for. We are collecting what the scientists need and that’s all that really matters to me.