By Dr. Tamara Frank - Chief Scientist, Nova Southeastern University, Halmos College of Natural Sciences and Oceanography

July 16, 2015

Sampling a bacterial mat. Video courtesy of NOAA Bioluminescence and Vision on the Deep Seafloor 2015. Download (mp4, 3.5 MB)

We arrived at the ship and immediately got to work unpacking our crates and setting up our labs. Because of the amount of work involved setting up the remotely operated vehicle (ROV), the ROV crew has been working steadily since yesterday.

Fig. 1 - A view of the wetlab aboard the R/V Pelican before equipment setup. Image courtesy of NOAA Bioluminescence and Vision on the Deep Seafloor 2015. Download larger version (jpg, 558 KB).

I got to my lab space and started unloading trunks and trunks of gear. Figure 1 is what the lab looked like when I started, and Figure 2 shows the final version.

Fig. 2 - A view of the wetlab aboard the R/V Pelican after equipment setup. Image courtesy of NOAA Bioluminescence and Vision on the Deep Seafloor 2015. Download larger version (jpg, 1.8 MB).

I’m sharing the lab with Sönke Johnsen, and he graciously allowed me to set up my equipment before starting on his set-up. I've put an arrow on his set-up to help you identify it (see Figure 3). He did have to track down an electric drill to get the two screws into the table. Am I envious that Sönke does such remarkable work on shipboard with such minimal set-up? Nah.

Fig. 3 - Sönke Johnsen's sparse equipment setup in the wetlab aboard the R/V Pelican. Image courtesy of NOAA Bioluminescence and Vision on the Deep Seafloor 2015. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

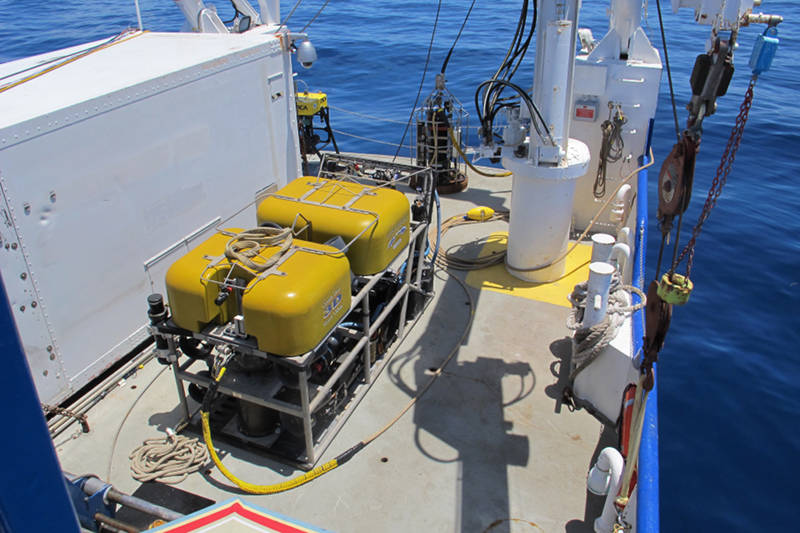

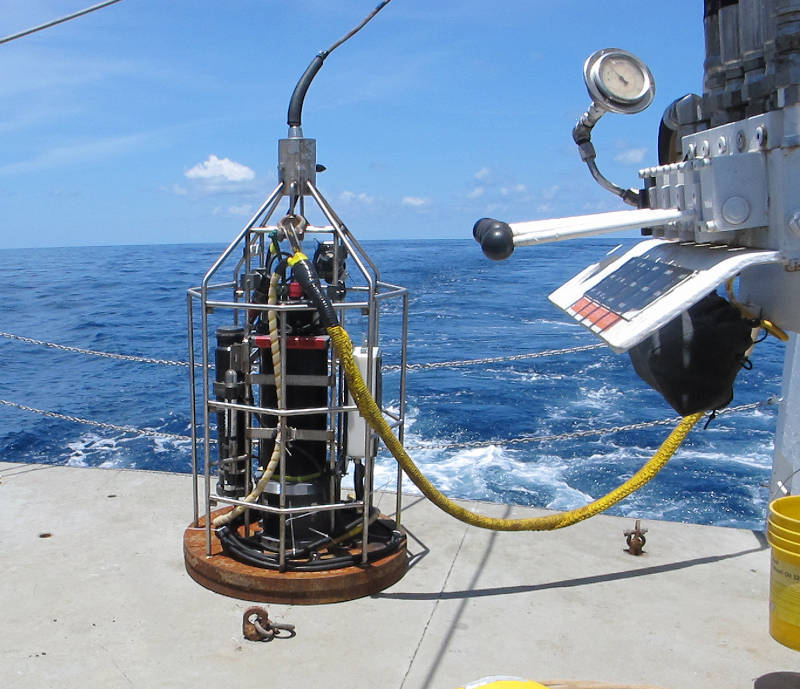

After completing the set-up, we (this being the royal "we" – the scientists sit back and watch the ship and ROV crew get the ROV into the water) had our first ROV dive. The ROV is deployed over the side, while the clump weight is deployed off the stern (backend) of the ship. The clump weight is attached to the wire that’s attached to the ship, while the ROV is attached to the clump weight by a tether. The tether between the clump weight and the ROV is 40 meters long. The pilot leaves some slack in the tether, which allows the ROV to work on the bottom without being affected by the ship's movements, even if the clump weight is bobbing up and down with the ship.

The ROV Global Explorer prepared to be dropped into the Gulf of Mexico. Image courtesy of NOAA Bioluminescence and Vision on the Deep Seafloor 2015. Download larger version (jpg, 2.4 MB).

A few things went wrong on the first dive, as they inevitably do when testing out new modifications to the collecting gadgets, but luckily, this site turned out to be relatively sparse in terms of bioluminescent animals, and we now know what needed to be fixed for the next dive. This site had a lot of methane seeps (where methane bubbles up out of the ground), and so we saw a lot of the tubeworms that are very common at these sites. There were also a fair number of crabs in amongst the worms, and, as we have seen with crabs at other sites, they were reaching over and picking food off the tubeworms (see video at bottom). At this point, we don’t know what they were eating, but maybe careful review of the video will tell us more.

The ROV Global Explorer clump weight being lifted into the water. Image courtesy of NOAA Bioluminescence and Vision on the Deep Seafloor 2015. Download larger version (jpg, 552.2 KB).

There were also large numbers of bacterial mats, both white and orange, which we are interested in studying for the bioluminescence capability. Unfortunately, when we were doing long-term exposures in the “dark,” it turned out that 500 meters during the day, the camera can pick up ambient daylight as well as the light from the clump weight 40 meters away. These mats are unlikely to have come from the surface on falling detritus; it’s more likely that they’re methane oxidizing bacteria, living off the methane seep out of the ground.

We're moving to another site now, where we will be spending a couple of days, allowing the first 24-hour deployment of the Image courtesy of NOAA Bioluminescence and Vision on the Deep Seafloor 2015. Medusa as well. This is a deeper site – 1,000 meters – so ambient daylight shouldn’t be a problem, and we’ll remember to turn off the lights on the clump weight as well.

Crab picking food off of tubeworms. Image courtesy of NOAA Bioluminescence and Vision on the Deep Seafloor 2015. Download larger version (jpg, 65 KB).