By Brian Philip Ulaski, Graduate Student, University of Alaska Fairbanks

This image captures a glimpse from the ship’s bridge, facing the stern of the Johan Hjort on the day of departure in Tromsø, Norway. Image courtesy of the Mapping the Uncharted Diversity of Arctic Marine Microbes expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 4.7 MB).

The day of departure was full of blue skies and smooth sailing. The conditions could not have been any better. Spirits were high. As the scientific team and vessel crewmembers gazed at the passing snow-covered fjords, the Johan Hjort was embarking on its route toward the heart of the Barents Sea.

Standing at the dock, about to board the Norwegian R/V Johan Hjort, my imagination explored what the next week and a half would have in store for me, aboard my first scientific cruise. Thoughts of collecting and filtering seawater for microscopic organisms atop rolling waves with an effort to maintain a sterile workplace seemed daunting, but I was ready to take on the rewarding challenge of science while at sea (foreseeing of a few inaugural hiccups of seasickness of course).

A view of the Johan Hjort anchored in calm waters. This image was taken from the ship’s tender, as the scientific crew made an opportunistic detour to Bear Island. Image courtesy of the Mapping the Uncharted Diversity of Arctic Marine Microbes expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 3.1 MB).

This sea-bound expedition accommodated a medley of scientific interests and goals with research themes ranging from parasites of fish to diversity of microbes, all with the unifying goal of garnering information on the structure of the Barents Sea’s pelagic and benthic communities.

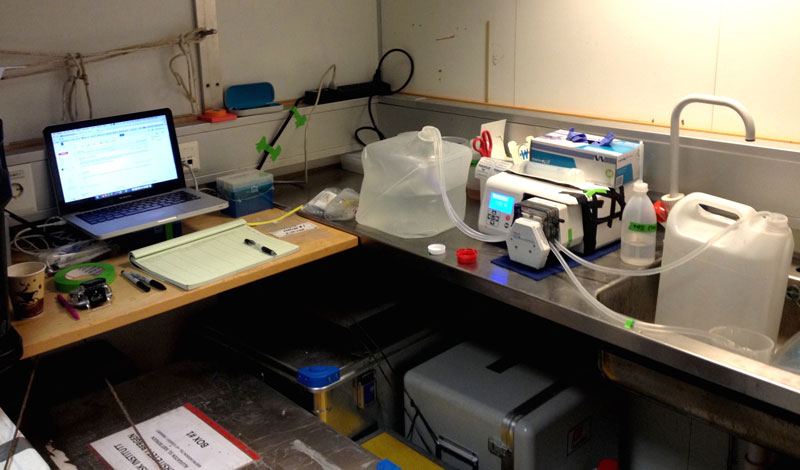

My role in all of this served the latter of the two themes. While on the ship, it was my job to collect and filter water samples from various depths of the water column at several predetermined stations along the way. Pumping the seawater through suitable filters (0.22 micron pore-size) is how the microbes were collected.

What microbiology may look like in a little corner of a small storage room on a large ship. Seawater obtained from Niskin bottles were collected in 10-liter carboys, transferred to this workstation, and pumped through filters using a peristaltic pump. The filters containing microbial cells were immediately frozen and awaited transportation to Alaska for genetic sequencing. Image courtesy of the Mapping the Uncharted Diversity of Arctic Marine Microbes expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 2.1 MB).

Approximately 400 liters of seawater were filtered in total by the end of the trip. Densities of organisms and turbidity of the water varied from station to station, and depending on this ‘thickness’ of the seawater, different volumes were capable of passing through the filters. In some cases, the seawater was so dense with organisms and other free-floating particles that fewer than 0.5 liters of seawater could be passed through a single filter. In other cases, up to 5 liters made it through with ease.

The goal was to concentrate enough genetic material (DNA/RNA) from a slew of microbial species within our water samples, giving insight to the bountiful diversity of the present microbial communities of the Arctic Ocean. The Barents Sea is just one, among several, Arctic locations our lab aims to address in the coming years.

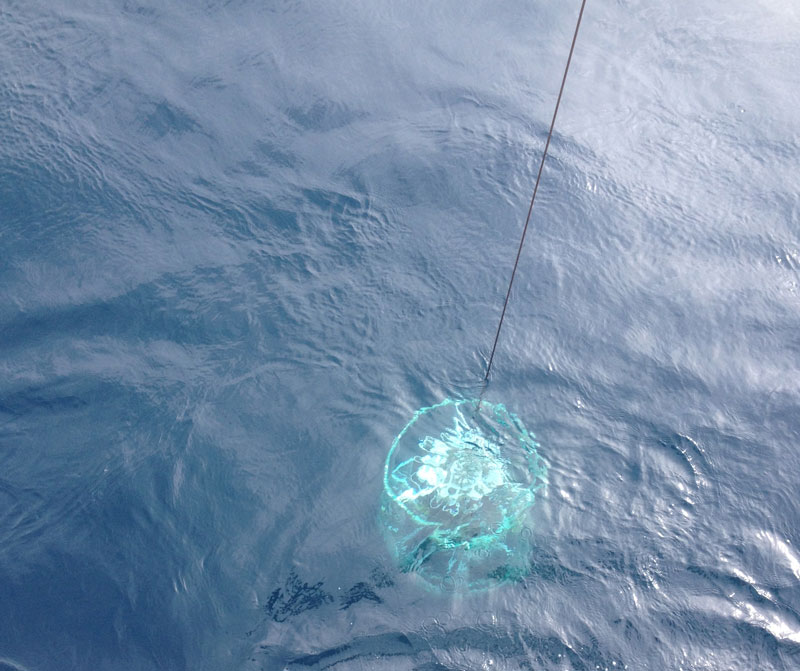

Down it goes! Casting a CTD into the deep blue. Instrument technicians trigger the closure of Niskin bottles at wanted depths for the collection of sample seawater. Image courtesy of the Mapping the Uncharted Diversity of Arctic Marine Microbes expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 2.5 MB).

Using next-generation sequencing technology, analyses of the diversity and distribution of Arctic marine microbes from the Barents Sea expedition will take place back at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Metagenomic sequencing will allow us to visualize this diversity, while laying groundwork for further and future studies of these tiny, yet biogeochemically paramount, microorganisms.

It is important to construct a baseline of knowledge on microbial communities that currently exist in Arctic waters. As a changing climate alters the state of this sensitive marine ecosystem, the more we understand now about the structure of these microbial communities, the better we can predict and aptly approach the inevitable changes that our current Arctic Ocean will undergo.