By M. Dennis Hanisak, The Cruise’s Chief Scientist and Research Professor - Florida Atlantic University-Harbor Branch

August 22, 2014

The University of North Carolina at Wilmington remotely operated vehicle recorded over 40 hours of video on Pulley Ridge during the Coral Ecosystem Connectivity 2014 exploration, including the Western Basin, unseen until now. Video courtesy of Coral Ecosystem Connectivity 2014 Expedition; Cedric Guigand, UM RSMAS; Brian Cousin FAU Harbor Branch. Download (mp4, 29.1 MB)

“Pulley Ridge is one of my favorite places on Earth. It continues to amaze me on each visit.”

One of the things I enjoy most about going to sea is exploring new sites: places that I’ve never seen before and, in some cases, places that no one else has ever seen. On this expedition, our Community Structure Team (Research Professor John Reed, Biologist Stephanie Farrington, and me from FAU Harbor Branch, and Heather Moe from the National Marine Fisheries Service) have been surveying unexplored sites at Pulley Ridge to more fully characterize its benthic community and biological resources. Our “eyes” for this work are the University of North Carolina at Wilmington’s Mohawk remotely operated vehicle (ROV), very ably piloted by Lance Horn and Jason White.

The job of the “Community Structure Team” is to document the ecologically important benthic community of Pulley Ridge. The first step is acquiring imagery with UNCW’s Mohawk ROV. Heather Moe (foreground) and Stephanie Farrington annotate incoming video in real time using specially designed keyboards to log species and habitat descriptions. Back in the lab, these images are meticulously analyzed and quantified, with results made readily available to appropriate resource managers and publication in scientific journals. Image courtesy of Brian Cousin, FAU Harbor Branch. Download larger version (jpg, 755 KB).

During our previous cruises in 2012 and 2013, we focused most of our ROV dives on the main Pulley Ridge, where we and other researchers believed the greatest concentration of corals to be located. This year we decided to spend our first few days working on sites off the main ridge. Each site consists of a 1 kilometer x 1 kilometer randomly selected block. We completed all of the planned sampling blocks, except one (“Block 31”) … by chance it was the last one left to do and also the farthest one from the main ridge … so surely the one least likely to have many corals.

We then went to what we call West Pulley Ridge, about an hour west of the main Pulley Ridge. Last year we spent one day of diving there, and we were impressed by the large diversity of sponges. We again found high benthic diversity, but few corals.

Next up was one day of diving at three sites not far from the western ridge, and where, to our knowledge, no one has ever dived before. Our bathymetric information (depth contours) often guides our selection of dive sites. On our charts, this area looked to be like a desert, with the two ridges off to either side. I began to call it “Death Valley,” not wanting to raise expectations too high! Our general thinking was this area was likely sandy bottom, one that would not support coral growth. But as scientists, we also know that all assumptions should be tested, and so we did.

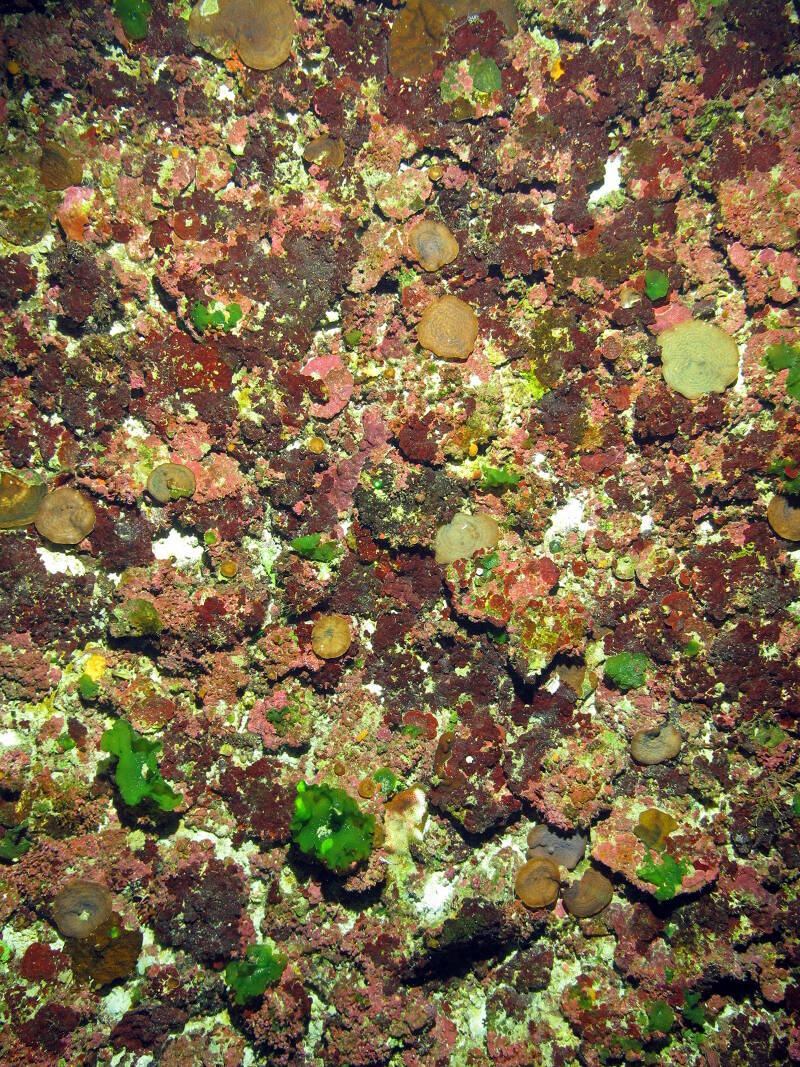

On today’s dive, we saw a large number of small colonies of plate coral (Agaricia spp.). This image, which has more than 20 small colonies of Agaricia, as well as two colonies of the coral Madracis, was taken with the Mohawk ROV’s downward still camera along a random photo-transect and is an example of the raw data that will be analyzed back in the lab. Image courtesy of Brian Cousin, FAU Harbor Branch. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 KB).

It turns out that “Death Valley” is full of benthic life, and, indeed, we saw more coral there (primarily Madracis, some Oculina) than we had seen on any of our previous dives this year. We may also have seen our first Porites in three cruises. Yes, we really were surprised … pleasantly so, of course … and no problem with realizing how wrong our simple assumptions had been! The absence of information did not equate to an absence of coral.

And we no longer refer to that area as “Death Valley,” but by the more respectful name “Western Basin.”

As luck would have it, for a number of other reasons, we decided to extend our stay at Pulley Ridge one more day, which gave us time to finish what we had missed earlier in the week. So we returned to Block 31 today, on the eastern edge of the Western Basin.

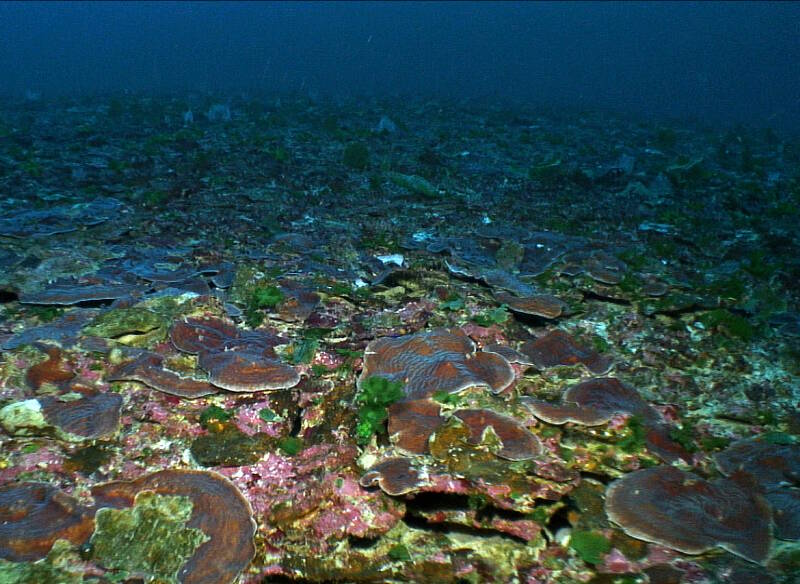

Today we were pleasantly surprised to discover large patches (up to 60 meters across) of nearly continuous plate coral (Agaricia spp.). This image is a screen grab from the high definition video taken from the Mohawk ROV. Image courtesy of Coral Ecosystem Connectivity 2014 Expedition. Download larger version (jpg, 949 KB).

As soon as the ROV reached bottom, we all realized that once again, we were in for a pleasant surprise. On this dive, we discovered an astonishingly large amount of plate coral (Agaricia spp.) … more than any we have seen (numbers of individuals and percent cover) here in the last five years. John, Stephanie, and I cruised here previously in 2010 and 2011.

Besides large numbers of small corals (10 centimeters or less), indicative of recent successful recruitment, we saw several large patches (up to 60 meters across) of nearly continuous Agaricia.

We had time to survey more sites, so we drew up two new boxes further west of Block 31. The coral area continued in those boxes, and likely extends further north and west. These coral populations, overlooked by all previous cruises (ours and others) are quite significant at Pulley Ridge and a major finding of this cruise.

A series of unplanned events led to a major discovery that we very easily could have missed! We may, after further surveying in the years to come, call this newly explored area “Coral Valley.”