By Felicia Coleman, Director, Coastal and Marine Laboratory - Florida State University

August 18, 2014

The industrious Red Grouper establishes complex habitat on the seafloor along Pulley Ridge. It digs pits as much as 5 meters across and 2 meters deep by scooping up sediment in its mouth and depositing it on the rim of the pit. Image courtesy of Don DeMaria. Download larger version (jpg, 704 KB).

Architecturally complex habitats arise from physical forces – wind, currents, and geological events or from the activities of resident organisms – beavers, prairie dogs, and. . .Red Groupers? Indeed!

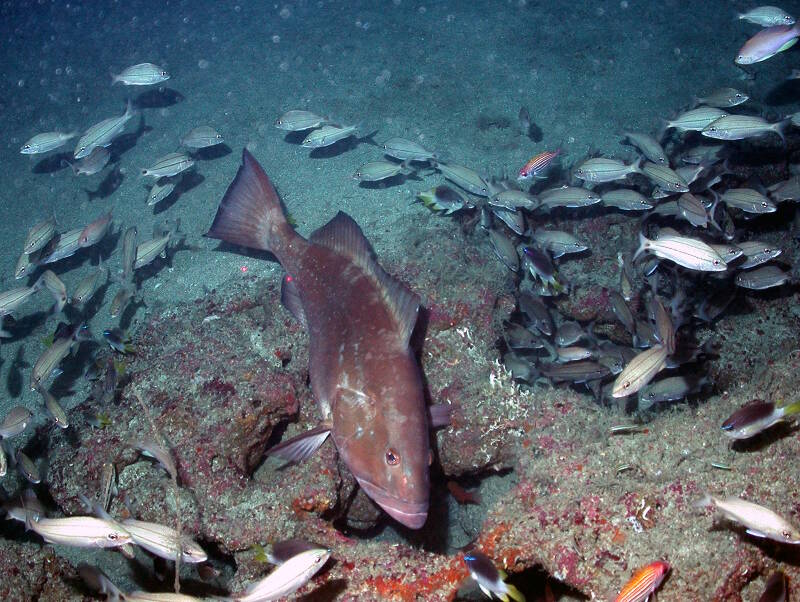

Many fish species, coral, algae and invertebrates take up residence in Red Grouper pits. Image courtesy of Coral Ecosystem Connectivity. Download larger version (jpg, 1.1 MB).

Red Groupers are highly territorial, remarkably sedentary seafloor architects, creating structure in areas otherwise appearing devoid of architectural complexity. Their engineering activity uncovers solution holes (formed by past fresh water incursions in limestone) or rocky outcrops that lurk beneath the often thick biogenic sediment cover, one mouthful at a time. Once the rock is exposed, Red Grouper maintain it by sweeping away sediment with their tails and removing by mouth larger dead shells and crustacean molts.

The invasive Lionfish has been found in increasing numbers at Red Grouper pits at Pulley Ridge. A quick count at one pit revealed 67 of the venomous Pacific species, raising serious questions for the scientists on the cruise. Image courtesy of Coral Ecosystem Connectivity 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

The constant clearing of sediment and debris from rocks by Red Grouper exposes ideal settlement surfaces for the attachment of algae, sponges, and corals. These sessile organisms, in turn, cover every nook and cranny in the rocks, thereby enhancing local habitat complexity. They do this passively as a function of their shape rather than a function of their behavior. The Red Grouper excavations or pits teem with mobile invertebrates—crabs, shrimp, and anemones—and fishes in a wide variety of sizes, colors, and forms, and thus, appear like small biodiversity hotspots.

These “hotspots” pock the edge of the West Florida Shelf from Madison Swanson Marine Reserve through Steamboat Lumps south to Pulley Ridge. Determining the level of connectivity between these offshore adult populations of Red Grouper and their inshore juvenile counterparts is one of the contributions that scientists at Florida State University’s Coastal & Marine Laboratory (FSUCML), Nova Southeastern University, and the University of Miami hope to make.

A curtain of small Tomtates and Vermillion Snapper finds refuge in a Red Grouper pit. Image courtesy of Coral Ecosystem Connectivity. Download larger version (jpg, 952 KB).

Among the many species that typically associate with Red Grouper excavations at Pulley Ridge are Longspine and Deepwater Squirrelfish, Reef Butterflyfish, Greater Amberjack, Almaco Jack, Striped Grunt, and Yellowtail Reeffish. Lionfish, not recorded during our 2002 study of Pulley Ridge, appeared by 2008 according to John Reed and now inundate the red grouper excavations we’ve seen on these cruises.

In fact, we rarely find lionfish in any other habitat on Pulley Ridge. The question is: are we witnessing local declines in biodiversity on these sites because of the presence of lionfish? If so, can we determine at what scale? Finding the answers to these questions is of intense interest to FSUCML scientists and will be addressed to the extent possible, based on data obtained from these cruises to Pulley Ridge.

To learn more about grouper and shelf-edge habitat, see these papers: