By Cedric Guigand - University of Miami

August 17, 2013

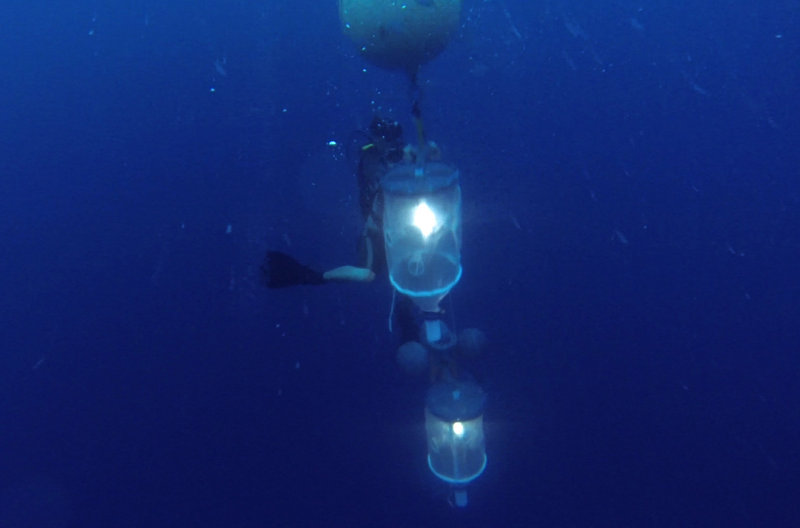

Cedric Guigand prepares to release two light traps into the depths, where they will collect young recruiting fish. Data are used to support biophysical models of species found at Pulley Ridge. Image courtesy of Brian Cousin, FAU Harbor Branch. Download larger version (jpg, 141 KB).

Yesterday, for the third night, FAU Harbor Branch’s Brian Cousin and I set our light traps right before sunset. The purpose of these traps is to catch young fish and invertebrates ready to settle from the plankton onto new habitat where they will metamorphose into juveniles. Many fish species release their fertilized eggs in the water column, where they start their journey from the open ocean and advance through their larval stage headed for suitable habitat to grow and live their lives. That's when we can catch them with our traps. The small recruiting fish, like moths, are attracted to the light.

We deployed two moorings from the deck of the research vessel. They stay in the water for the duration of our collection period, in this case 4 days. Each night we take plankton nets with lights inside and scuba dive to attach them to the submerged moorings. A 20-pound weight pulls the nets down a cable into the depths. The divers surface and deploy a third net just a couple of feet below the ocean waves.

Cedric Guigand, University of Miami (center) and crewmembers of the Walton Smith deploy a light trap mooring over the stern of the vessel. A railway train wheel is used to anchor the buoyant steel buoy. One of the plankton net frames is on the deck to the left of the mooring. Image courtesy of Brian Cousin, FAU Harbor Branch. Download larger version (jpg, 1.0 MB).

Overnight, the light traps ‘fish’ for samples. A calibrated metal link that holds the weight to the deepest trap corrodes in the seawater. The weight drops away, the deep trap floats up to meet the mid-depth trap and they both rise together to the mooring ball, where the scuba divers remove the nets and take them back to the ship for processing.

The dives on these offshore moorings are always full of surprises, as the solid structures attract all kinds of species in this usually all-water world. Ocean triggers follow us, schools of small jacks play around the moorings, sometimes sharks cruise by for a look. Swarms of tiny plankton drift by, many glowing in the ocean dimness that occurs just after sunset and just before sunrise. It will be interesting to see if we pick up any pre-settlement juveniles of the invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans), which we know from ROV videos are quite abundant on parts of Pulley Ridge.

Cedric Guigand and Brian Cousin rinse a net to concentrate the organisms captured in the light trap for identification. Image courtesy of Brian Cousin, FAU Harbor Branch. Download larger version (jpg, 540 KB).

On board the R/V F.G. Walton Smith, contents of the light traps are rinsed, sieved and taken to the lab for sorting and basic identification. Back in the university labs they will be identified to the lowest possible taxon, using molecular techniques to get to the species level.

Data collected from this offshore cruise will be part of the information going into a biophysical model that simulates larval movement, growth and survivorship, taking into account larval interactions with the pelagic physical environment (temperature, salinity, currents) and the benthic habitat, and is designed to explain population connectivity between deep and shallow reef systems. A good deal of the data already exists and has been used in model development. Our new larval settlement information adds a means of validating the model.