By Deepwater Canyons Project Science Team

May 8, 2013

A lithodid crab seen on the mussel bed at 1,600 meters. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 1.1 MB).

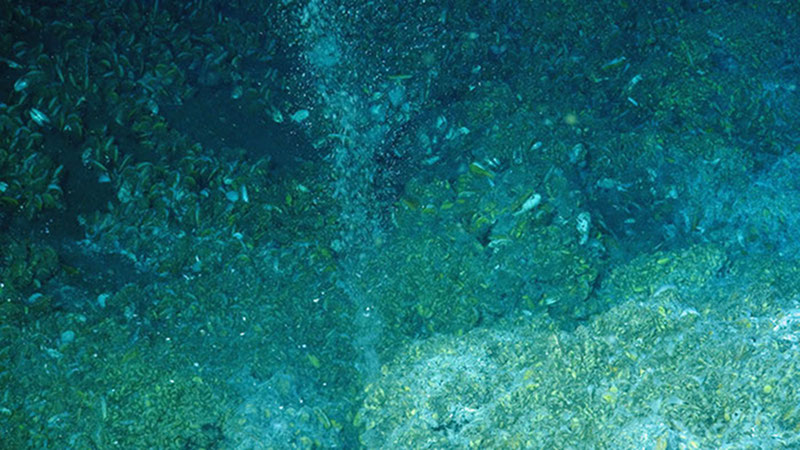

After several days of lost dives due to bad weather and making dives under difficult conditions, we are today in calm seas exploring an area that was discovered last year during a NOAA mapping cruise. While conducting a seafloor survey, NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer found bubbles coming from the seafloor at a site south and offshore of Norfolk Canyon; they thought these bubbles may indicate a new methane seep site, but they had no way of verifying this idea.

Methane gas bubbles rise from the seafloor – this type of activity, originally noticed by NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer in 2012 on a multibeam sonar survey, is what led scientists to the area. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 851 KB).

Today, we deployed the Jasonremotely operated vehicle (ROV) from the NOAA Ship Ron Brown to 1,600 meters (nearly a mile deep—our deepest dive yet!) to explore the area around those bubbles. After transecting over soft sediment for a short time, we saw some indications that we were getting close to a probable methane seep. These indications included white patches of bacteria on the sediment surface that feed on the methane and sulfides, plus shells of dead mussels, which are the dominant animals of methane seep communities.

These mussels have specialized bacteria that live in their gills and use the methane to make energy. These chemosynthetic animals (that is, those that rely on chemicals such as methane or sulfides) are unusual as they do not rely on energy from the sun, as almost every other organism does, however indirectly. They use an alternative energy source—one that may have been employed long ago in the depths where the Earth’s crust split apart and released the heat and chemical fuel needed to jump start life in our oceans. This constant energy supply allows large numbers of mussels and other animals to accumulate, thriving upon the chemicals seeping from the ocean’s floor.

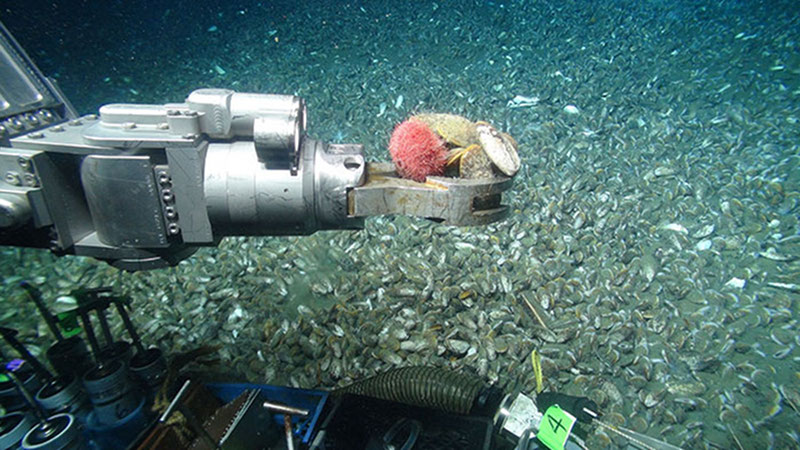

Jason collects a sea urchin and a few mussels from the expansive mussel bed with its manipulator arm. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 866 KB).

The first patch of live mussels we saw was cause for great celebration—we had confirmed the suspicions of the scientists on the Okeanos Explorer last year and found a brand new seep site, one of the very few currently known off the U.S. Atlantic coast. The best known seep is off South Carolina in very deep water (2,500 meters) and the second was re-discovered in more shallow depths (400 meters) at the edge of Baltimore Canyon during our expedition last year.

The vast mussel community was found on flat bottom as well as on rocks rising a meter or more off the seafloor. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 1.0 MB).

Although the first patch of live mussels we found was quite small, the second patch was larger, and the third mussel patch covered an area over 20 meters across. This patch was packed with live mussels, plus a variety of fishes and invertebrates, including soft-bodied sea cucumbers that were tangled among the mussels.

Continuing on, we soon came across densely packed mussels that carpeted the bottom as far as Jason could see! The dense aggregations of mussels resembled what we often observe in rocky intertidal environments. Thick, white, bacterial mat—like a shag carpet—covered many of the mussel shells and made filaments that slowly wave back and forth.

Once the jubilation of discovery was over, it was time to get to work. We took sediment cores so the U.S. Geological Survey scientists could examine the animals living in the mud and the bacterial mat on the sediment surface. We also collected some rock samples and large dead mussel shells for ageing analysis, plus several live mussels for genetic and reproductive studies. The associated fish and invertebrates will also be used for research into food webs, to determine whether the methane is indirectly providing food for a wider community of animals living around the seep.

Members of our research team have studied cold seeps in the Gulf of Mexico (Expedition to the Deep Slope 2006 and 2007), so we will be able to compare samples and observations from this site with those from the Gulf where cold seeps are more numerous and better studied.

Although many comparisons between Gulf and Atlantic seeps will continue back at our labs, an obvious difference is the absence of two seep-related species that do not occur in this new Atlantic seep but are common in the Gulf: tube worms and galatheoid crabs.

A species of rockling (Family Lotidae), related to hakes and cods, rests among the mussels. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 830 KB).