By James Connors, Web Coordinator - NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

May 5, 2013

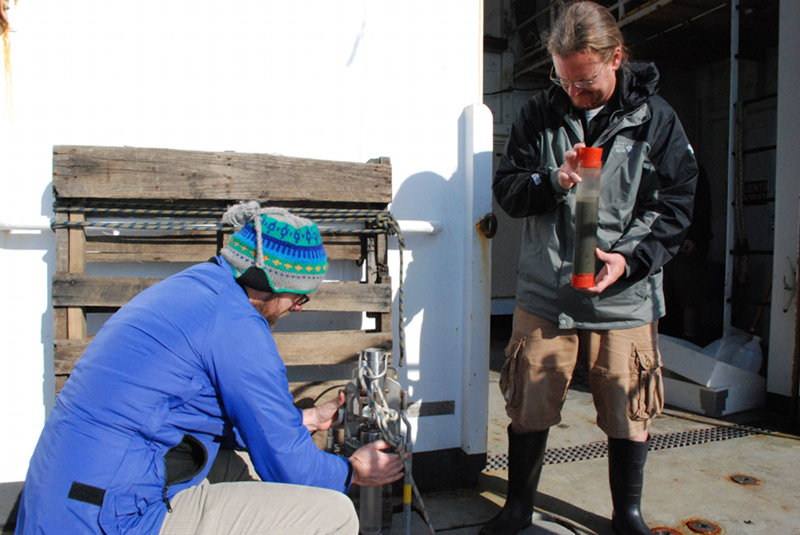

Mike Gray (right) holds a complete core sample from the monocore while Craig Robertson prepares it for the next deployment. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 562 KB).

Three days ago, the Jason remotely operated vehicle (ROV) plunged into the Atlantic for its first dive on Norfolk Canyon. Spirits were high, but unfortunately the dive was somewhat less productive than expected. Severe bottom turbidity, a mass of floating sediments that Co-Chief Scientist Steve Ross explained to be the "Nepheloid Layer," cut visibility short and hampered Jason’s productivity.

In the two days since, surface wind and subsequently ocean waves have intensified, making it unsafe to launch or recover Jason. In lieu of daily ROV dives, the science team has busied itself with an array of observation and sampling methods originally scheduled during the night.

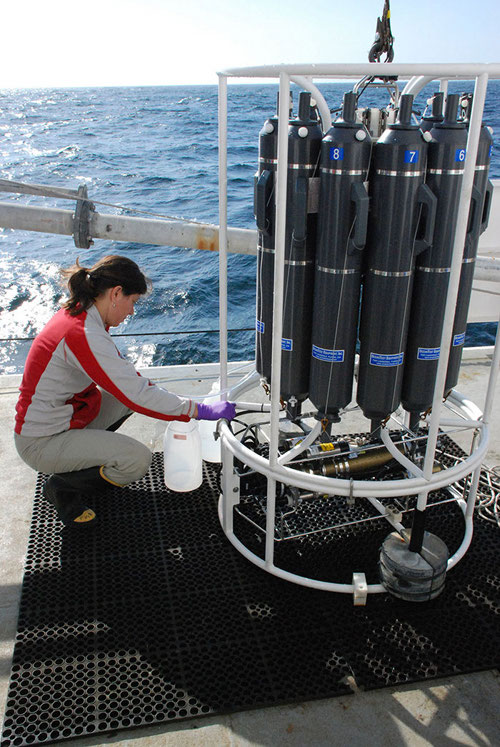

The CTD is grabbed and hauled back onboard after collecting seawater and data. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 779 KB).

The most fundamental of these methods is water column profiling, using a CTD and Niskin bottles attached to a rosette. The bottles are open at both ends as the CTD is lowered to the ocean bottom, and close at specific depths on the way back up. The water collected from the bottles is measured for amounts of chlorophyll (and other phytoplankton pigments), particulate organic matter, and specific radiocarbons present. This information helps determine where the water came from, what is living in it, and how its properties change from surface to seafloor.

Core samples can be collected three ways on this expedition: with a small, tubular device that hangs off the CTD (called the mono-core); with push-cores kept in Jason’s sample tray that are directly set into the seafloor with the ROV’s manipulator arm; and with the box corer, a larger tool launched off the stern using the Ron Brown’s A-frame.

Scientist Nancy Prouty collects water from the Niskin bottles on the CTD after deployment. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 715 KB).

In all cases, the objective of the core sampling is to collect an undisturbed section of seafloor, and often the water immediately above it. Once the core is acquired, it is sectioned and preserved. Scientists onboard are interested in the chemical constituents of the cores, the amount and freshness of the organic matter (food) they hold, and what infauna (small animals living in the sediment) is present. In trying to build a complete picture of the canyon ecosystem, an understanding of the production occurring in these soft sediments is essential.

The least sophisticated sampling strategy is simply to trawl, that is, tow a net along the seafloor. The net we’re using is much smaller than a conventional fishing trawl, and our target area is limited to the muddy interior of the canyon rather than its rocky slopes, but trawling is a relatively easy way to get a variety of organisms onboard for study. Trawling allows for a general survey of seafloor life, and occasionally more in-depth work if the right species are found.

The catch from a trawl is brought inside and sorted in the lab. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 805 KB).

Two groups of U.S. Geological Survey scientists work with samples collected from the trawl; one performs isotope analysis on specimens to determine their diet and construct a canyon food web, while the other studies genetic variation among populations of deepwater crab. In addition, the reproductive biology of dominant benthic fauna, especially corals and echinoderms, is being studied by Dr. Craig Young at the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology and Dr. Sandra Brooke at Florida State University. The trawl catches have provided some excellent material so far, some of which is being kept alive in tanks for further studies.

Between the CTD work, bottom coring, and trawling, everyone onboard has stayed quite busy, even though Jason remains strapped to the ship’s deck. And though we’ve spent the last two days feeling a little nauseous in the high seas, we continue to make progress in our goal of better understanding the canyon ecosystem.