By James Moore, Marine Archaeologist - Bureau of Ocean Energy Management

May 23, 2013

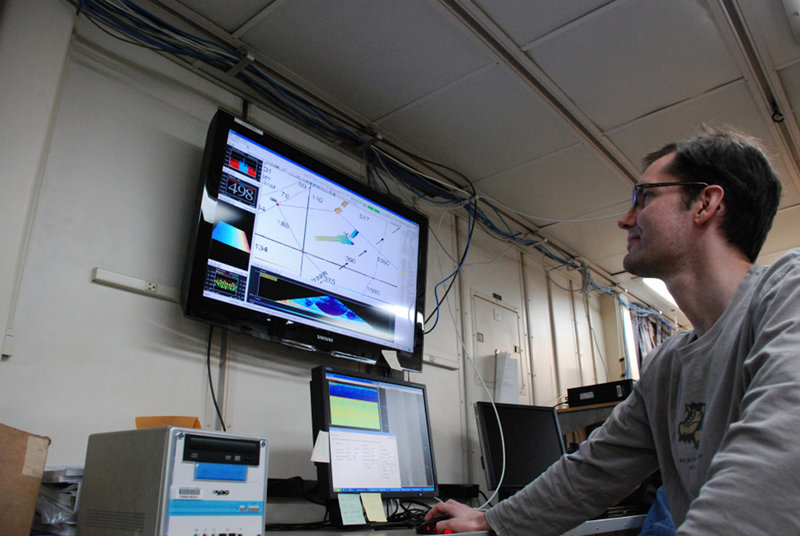

BOEM Archaeologist James Moore lays out survey track lines and interprets multibeam data. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 4.9 MB).

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), which is within the Department of the Interior, has the responsibility of overseeing the development oil, gas, and renewable energy industries along the United States’ Outer Continental Shelf (OCS). Applied scientific research, therefore, must be implemented to identify potential environmental impacts that may occur from developmental and operational activities associated with these industries, which leads to measures that will eliminate or reduce these impacts.

Results from BOEM’s applied scientific research studies may then be used to inform policies concerning America’s offshore energy resources.

Scientists and crew aboard NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown anxiously await the results of multibeam surveys, hoping to identify new shipwrecks. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 5.3 MB).

BOEM is also responsible for mitigating the impacts that these industries may have on submerged archaeological sites, such as shipwrecks. Very few data are available, however, in regards to the types and locations of deepwater shipwrecks along America’s OCS. This study, in conjunction with the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research and the U.S. Geological Survey, has provided a unique opportunity to better understand how the marine environment impacts shipwrecks and how these archaeologically important sites function as artificial habitats for diverse biological communities, including coral and fish species.

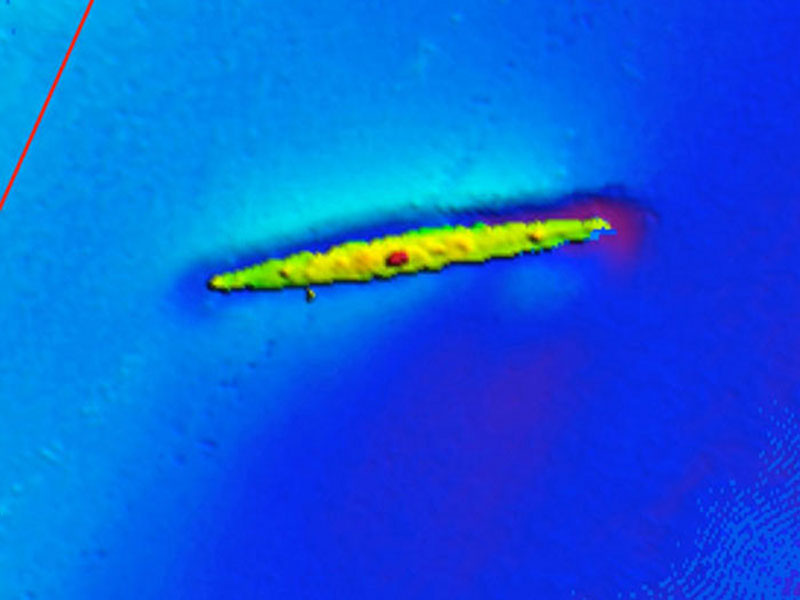

This high-resolution multibeam sonar image of a shipwreck on the continental shelf near Norfolk Canyon (not collected during the Deepwater Canyons 2013 expedition). Image courtesy of Rod Mather, URI. Download image (jpg, 48 KB).

As a marine archaeologist, I always find the discovery of new shipwrecks, especially in deepwater environments, to be exciting. However, the process of finding and then exploring such sites can at times require a strong sense of patience and the coordination of many efforts.

The first step to locating a shipwreck usually involves analyzing sonar data that have been collected and processed to create an image of the sea floor below the research vessel. Any targeted anomalies of a noted size that are detected from this image are then marked for later visual inspection, a method known in archaeology as ground-truthing. In the deeper waters of the OCS, a remotely operated vehicle (ROV), such as Jason, is required inspect and determine what the sonar targets may be.

Large, metal-hulled shipwrecks typically have a distinct sonar image, allowing for easier identification. Smaller vessels or those originally constructed from wood, which can rapidly degrade in marine environments, are more challenging to determine. In this case, a target that was originally perceived to be a shipwreck may actually turn out to be a geologic feature or modern human debris. So, there is often a sense of anticipation and a new sense of discovery each time the ROV is launched to explore a new target.

Due to the extreme depths of the OCS, we must also be keenly aware of any potential changes in the weather, such as high winds and/or storms that may create conditions that are too unsafe to launch undersea vehicles. Such conditions can delay or cancel planned ROV launches, which is disheartening, but we all understand that unplanned schedule interruptions are part of life at sea, and plans are rapidly adapted so time aboard the research vessel is used efficiently used. The eagerness to discover and learn about new shipwreck sites, though, definitely keeps up our spirits with a healthy sense of optimism.