By Kasey Cantwell, Expedition Coordinator - NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

May 22, 2013

After an early morning radio call, NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer met NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown to deliver the replacement part for the EM122 multibeam sonar. Image courtesy of Walt Gurley, Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 5.4 MB).

One of the most intriguing things about science at sea is that you are able to travel to remote undersea locations, usually places that few people are ever able to see. With a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) like Jason, we are able to explore areas and depths that humans could not physically visit due to the extreme pressure of the deep ocean. These sites are often far offshore and can only be accessed by a large ocean-going vessel.

This isolation begins to work against you when something on the ship malfunctions, as it did for NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown early this morning. Around 1 am, we were given the news that the multibeam sonar system, used to map the ocean floor, was not working and that the operations planned for the rest of the cruise would not be possible. We spent the rest of the morning reprocessing multibeam data we already had, re-planning our operations, looking at second and third alternatives, and trying to find a solution to this issue.

We decided to transit back to other known sites close to where we had been working for the first few days of the cruise, potentially giving up the opportunity to locate and identify new deepwater shipwrecks. Fortunately, we had a representative from Kongsberg, the manufacturer of the multibeam system, on board who was able to contact his counterpart in Norway, where the company is headquartered, and troubleshoot the problem.

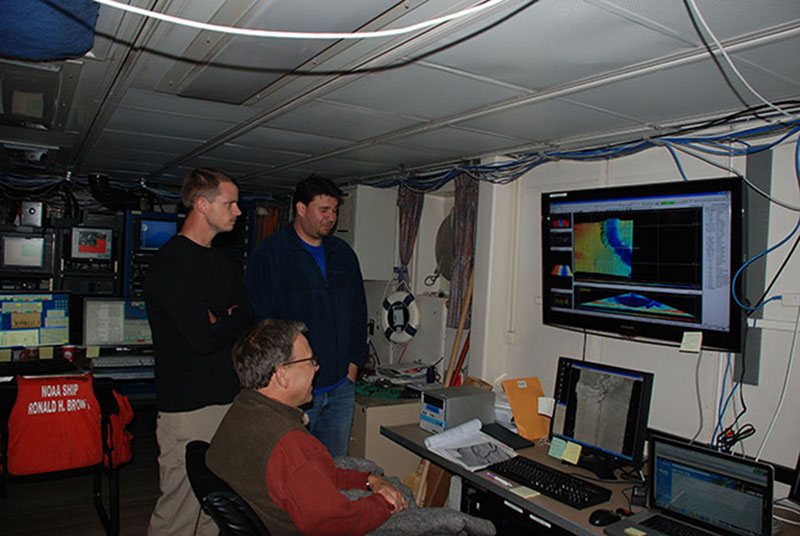

After repairing the multibeam system, Kongsberg representative Tony Dahlheim, data manager Keith Vangraafeiland, and archaeologist Frank Cantelas assess the live multibeam feed coming in from the EM122 hoping to spot new deepwater shipwreck targets. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 4.4 MB).

We were twice as lucky when it turned out that the replacement part that we needed could be found on the nearby NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer and that they were only a couple hours away. The Okeanos Explorer crew agreed to head north and the Brown changed course for the second time in only a couple hours. At 8 am this morning, the two ships met and transferred the replacement part via small boats.

As the Okeanos Explorer departed, we anxiously awaited whether the new part would solve the issues in the sonar mapping system. With the replacement installed and a full diagnostic test run, our mapping system was fully operational. Without the helpfulness and resourcefulness of both ships’ crews and the Kongsberg representative, our cruise would have been severely compromised.

Things at sea are always unpredictable and usually the only way to handle that is to be creative and adaptable.

After careful consultation with the Commanding Officer of NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown, ROV Jason prepares to cut free an abandoned fishing net suspended by floats from a shipwreck to allow for better navigation during mosaicing. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

Instead of heading back out immediately to map new areas with the repaired mutibeam sonar, we decided to spend the day re-examining a shipwreck explored last year. After a couple hours of sleep, I was happy to find the Jason ROV in the water and beginning reconnaissance. Following the initial investigation, Jason began running photo transects about four meters above the wreck using the downward-looking camera.

Photo mosaics of the shipwreck targets are one of the highest priorities for Co-Chief Scientist Rod Mather. I was particularly interested in this as for four years before joining NOAA, I conducted coral reef monitoring using photo mosaics. Although mosaicing a deepwater shipwreck with an ROV is very different from mosaicing on a shallow coral reef on SCUBA, the process is very similar in terms of imagery collection.

The first thing that struck me as different was how slow the ROV was transiting. Using diver-based mosaics, I was able to collect two images per second with approximately 70 percent overlap while swimming across the site. The ROV collects downward-looking images with approximately 50 percent overlap once every 10 seconds at a speed of 0.1 knots.

Each line of the mosaic today took approximately 15 minutes. Granted, shipwrecks are much larger than the reefs I am used to surveying, but I would usually swim about twice as fast, if not faster, than the ROV.

One of the most difficult issues with collecting mosaic imagery from an ROV is the loss of depth perception. Video screens in the ROV van are two-dimentional versus being able to see a shallow reef with my own eyes in three dimensions. Along the same lines, an ROV cannot twist its head to look around at the surrounding potential obstacles to adjust its course or altitude. Light does not penetrate to the depths of our sites and the visibility is several orders less than on a shallow coral reef.

Both of these factors add challenges to attempting to navigate the ROV and cameras over an already challenging shipwreck. To make matters worse, these wrecks have been significantly damaged in recent years by commercial fishing gear. Today’s wreck had many snagged trawl nets suspended by floats in the water column, one floated up 20 meters above the hull. At the end of the dive, I was exceedingly impressed with the navigation skills of the Jason pilots who were able to collect great data in a very hazardous environment.

Tonight we will head to deeper water and use the Ron Brown’s newly restored full ocean depth multibeam sonar mapping system to try and detect the presence of deepwater shipwrecks!