By Terry Connell, Web Coordinator - NOAA's National Ocean Service

September 24, 2012

Chain catsharks and mermaid’s purses (egg sacks from these sharks) on a wreck site. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM. Download image (jpg, 94 KB).

The morning Kraken II remotely operated vehicle (ROV) deployment was picture perfect. The crew of the ROV spent hours carefully documenting another of the ships sunk during the Billy Mitchell air bombing experiments. The ROV monitor showed a steady stream of incredible images of the wreck. The sea is unforgiving and unrelenting in its reclamation. What was once a weapon of war is now a living reef, teeming with an abundance of sea life.

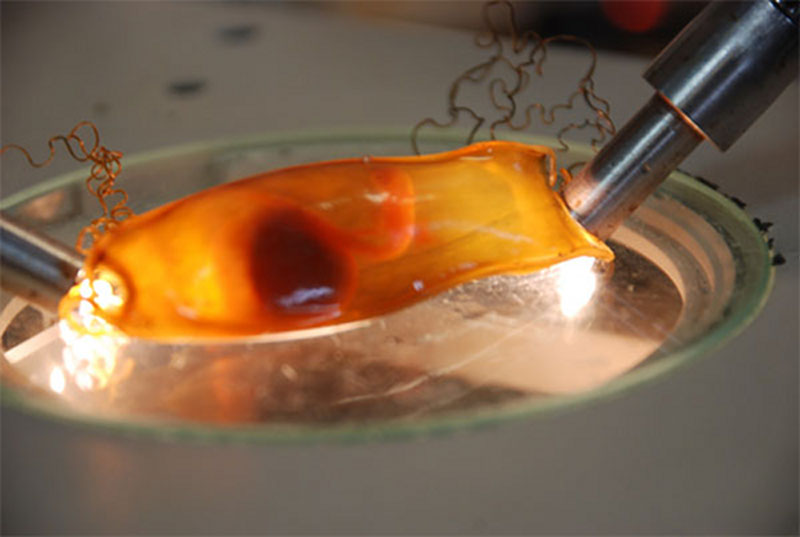

Mermaid's purse, collected by the Kraken II, ROV, with reflected light showing the shark embryo. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM. Download image (jpg, 52 KB).

Midway through the operations, the Kraken II’s lateral thruster failed and the adept operators were forced to maneuver the ROV using only the forward and backward rotary thrusters. Operations continued and the documentation was completed as planned. As they moved along, the scientists made notes of things that they would like to collect and the last hour or so of the dive was spent collecting those samples on or near the wreck for further study.

Trawling nets, floats and fishing lines are as common on these wrecks as the chain catshark. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM. Download image (jpg, 58 KB).

One of the notable things about these wreck sites are the huge numbers of chain catsharks (aka dogfish). They are everywhere – draped in piles over the ships and littering the ocean floor around the wrecks. Chain catsharks are a small, (usually) harmless benthic, or bottom dwelling, shark that can be found along the western Atlantic from Maine all the way to the Caribbean and into the Gulf of Mexico.

These sharks prefer to stay in the deeper water of the outer continental shelf and upper slope, preferably on rough, rocky bottoms. But the smooth, sandy bottom around these shipwrecks is anything but rocky. And here, they congregate by the thousands.

Within these shipwrecks, the juvenile shark have plenty of hiding places and lots of food. The diet of the chain catsharks is fish, crustaceans, and cephlapods, all of which live in abundance around these wrecks and could be the biggest reason for the mass congregation.

Operators of the Kraken II use the mechanical tools to collect samples, like this spider crab, near the shipwrecks for further study. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM. Download image (jpg, 84 KB).

Perhaps their favorite thing to eat is the spider crab, which might explain the sudden attack on the Kraken II after it grabbed one of these intriguing crustaceans for part of the study. As the Kraken’s claw dropped the crab into the collection box and closed the lid, one of these otherwise quiet and benign sharks appeared to attack the ROV. In seconds, the ROV was crippled as yet another thruster failed, officially ending the operations for the day.

Normally, the crew of the Kraken II assists the recovery efforts. Once the pressor is recovered, the ROV’s thrusters help propel it towards the ship so there is no resistance on its cabling and then stabilize its position while it is captured. Without those aids, recovery is a bit trickier, but the crew managed to pull it off and the Kraken II ROV was safely captured and gently placed on the deck for inspection.

Normally, as shown here, the crew uses the ROV’s thrusters to bring it into the recovery range, keeping tension off of the umbilical. Once at the back of the ship, those same thrusters help keep it steady while it is gaffed and prepared for hoisting onto the deck. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM. Download image (jpg, 115 KB).

The pressor is captured using gaffs, which allow a line with a quick catch to be attached to the frame. Once the pressor has been brought onboard using the winch and hoist, the ROV is recovered. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM. Download image (jpg, 94 KB).

The ROV wasn’t onboard more than a few seconds when the problem was immediately apparent – chain catsharks! Halfway through the dive, one of these fish had become lodged in the blades of the lateral thruster. During the collection process and subsequent “attack“ on the ROV, the crippling blow came when a second shark became lodged in the vertical thruster, burning out the motors and blowing fuses on the ROV.

One of the ROV's thruster motors, burned and melted when the catshark wedged itself in the propeller blades. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM. Download image (jpg, 62 KB).

Where does that leaves us? The Kraken II ROV has been diving, in its current form, since 2006. There have been lots of technological issues to overcome over the years, but nothing like this one!

From time to time, creatures do wander into these propellers. Usually the sharpness of the blades takes care of any issues and provides an easy meal for nearby creatures.

But, sharks have tough skin and the two offenders completely jammed up the propellers. Both motors were badly burned along with connectors and fuses. The team had one replacement motor, which they installed.

After some repair work, the Kraken II was back up and running, but without lateral thrust. Let’s hope the sharks leave it alone!

The offending sharks, a male and female chain catshark, have dedicated their lives to science. They will be carbon iso-sampled and shipped back to the lab with other collected benthic samples from this mission. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM. Download image (jpg, 53 KB).