By Scott France - UL Lafayette

September 10, 2012

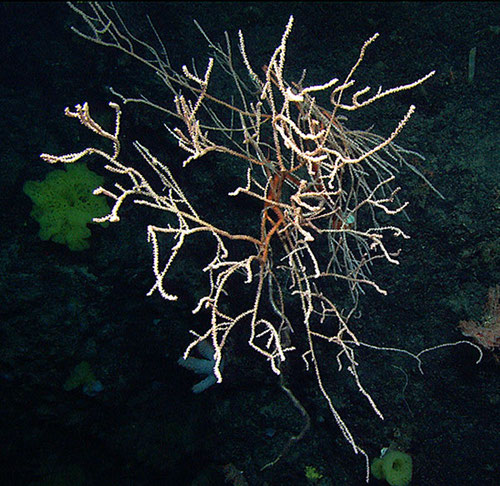

A large colony of the bamboo coral Eknomisis dalioi at 1916 meters depth reaches out from Rehoboth Seamount. This colony was sampled during the 2005 NOAA-OE sponsored mission Deep Atlantic Stepping Stones. Upon further taxonomic analysis in the lab it was determined to be a new species and is one of the type specimens. The genus name comes from the Greek “eknomios“ which means marvelous or wonder, and the species was named in honor of Ray Dalio on the occasion of his retirement from the Board of Directors of the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. It was formally published in 2011. Image courtesy of the Deep Atlantic Stepping Stones Science Party, IFE , URI-IAO, and NOAA. Download image (jpg, 94 KB).

Somewhere in France locked up in a vault is a golf ball size block of metal - more specifically an alloy of platinum-iridium –that weighs* 1 kilogram (kg). Exactly 1 kg. In fact, it is the world standard for 1 kg. If there is a question about the accuracy of a scale, such as the one in your bathroom, use of this block would be the ultimate form of calibration: it is 1 kg and so a scale must be adjusted to match this weight. A similar concept is used in the process of assigning formal scientific names to organisms (taxonomy). Species are given formal scientific names after careful analysis of their characteristics [these days that would include their DNA sequences]. The familiar system for classifying named species began with Linnaeus in 1735.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries there were a number of deep-sea expeditions that brought to scientists’ attention many previously unknown coral species. A series of publications associated with those expeditions described (assigned names to) the 1000s of new species that were discovered (more than just corals). Today, using ROV technology, we have the luxury of seeing these deep-sea corals, crabs, fish, anemones, etc., in their habitat. How do we know if these are the same species as those collected by the 19th century scientists?

The papers they published provide anatomical details that allow experts to identify them. But sometimes we find individuals that don’t quite match the description; perhaps these are new species? In other cases, the old publication doesn’t have enough detail to distinguish among some species that were described using more modern techniques. For example, since the 1970s, it is standard to use scanning electron microscopes to obtain fine-scale details of morphology of octocorals and black corals, but this tool had not yet been developed earlier in the century and so descriptions of morphology at that scale were not possible. Before we can claim that the specimens that don’t conform to existing species descriptions are indeed new species, we need to compare to a standard.

Dr. Scott France examines a sample of coral collected on the first leg of this mission. This deepwater sea fan in the family Plexauridae, appears yellow when alive but after being preserved in ethanol for DNA studies has leached purple pigments. Image courtesy of the Deep Atlantic Stepping Stones Science Party, IFE , URI-IAO, and NOAA. Download image (jpg, 77 KB).

In taxonomy, such standards are called “type“ specimens for the species. “Types“ are specimens that the scientist who named the species was looking at when he wrote the description. They are deposited in museums for long-term storage. So, as a researcher I can go to the museum that houses the type for a particular deep-sea coral, and compare it to my new collections. My colleague Les Watling (University of Hawaii) and I have been doing this with a bamboo coral that was described in 1883 from specimens collected in a canyon not far north from where we are working on this cruise, and which is stored at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. Last year Les and I described a new species of bamboo coral – Eknomisis dalioi – and deposited the types in Yale University’s Peabody Museum; those specimens will be available for future generations of scientists.

There are some problems with the “type“ concept. If there is only a single specimen preserved, it likely would not encompass the range of morphological (or genetic) variation seen among individuals of the species. But it does at least provide the actual specimens the person who named the species was looking at when he or she made the description, allowing for direct comparison rather than interpretation of, sometimes incomplete, notes.

Today, scientists are trying to develop an alternate form of standard: a molecular barcode that would be unique to each species. The DNA that makes up your genes has been described as the blueprint of organisms. Can we find a gene whose sequence of DNA bases (nucleotides) could be used to separate all species, just as a barcode is used on products at the grocery store? Such a gene would have to show enough variation that all species could be distinguished from one another, but not so much variation that all individuals within a species were different (there are other technical issues to consider that I won’t get in to here). Although we have not yet found the perfect barcode that works across all organisms, much promise has been shown with a gene called cytochrome oxidase I (COI, or cox1). The DNA sequences of these molecular barcodes are stored in online databases (e.g. GenBank, BoLD ), available for anyone to examine. If these barcodes are combined with type specimens, we have considerable information to match up long-ago described species with the specimens we observe today.

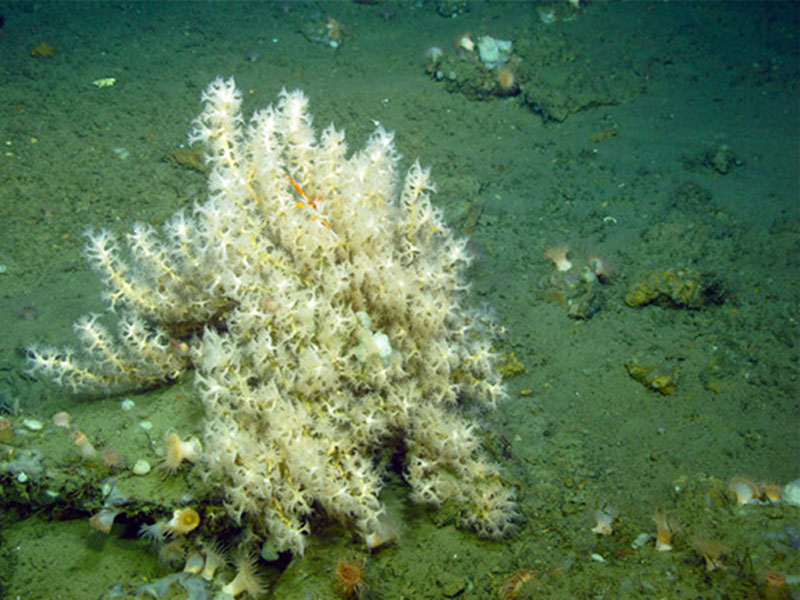

A colony of Anthothela coral in the Baltimore Canyon at a depth of approximately 600 meters. When we collect and observe these corals, we assign them a tentative identification. Later in the lab, back on shore, we do further analysis to get an exact species identification. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM. Download image (jpg, 125 KB).

How many species do we have in different environments on Earth? Are some ecosystems and communities richer – that is, with more species – than others? How does this richness affect the ecology of the system? In order to measure biodiversity, we need to know how many species there are. One of my research interests is in describing the diversity of deep-sea corals.

*Technically it has a mass of 1 kg, but for convenience it is commonly used as a measure of weight.