By Steve W. Ross - UNC-W, Center for Marine Science

and Sandra Brooke - Marine Conservation Institute/OIMB

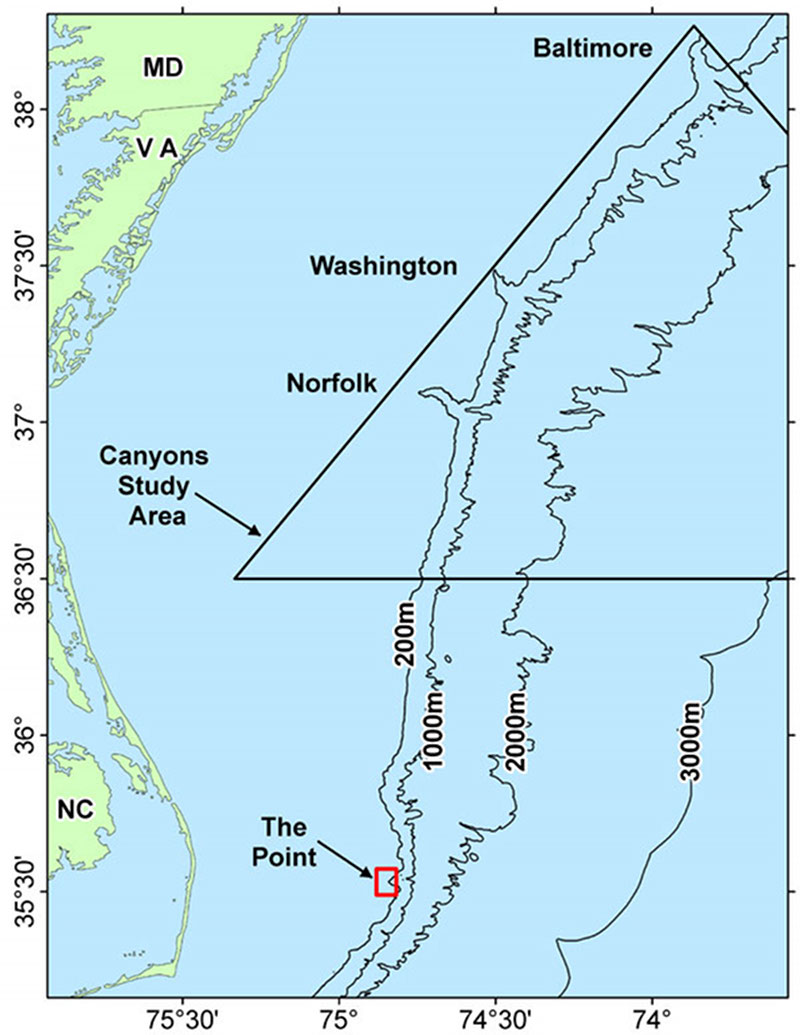

Submarine canyons are dominant features of the outer continental shelf and slope of the US East coast from Cape Hatteras to the Gulf of Maine. Image courtesy of Steve W. Ross, UNC-W. Download image (jpg, 117 KB).

Submarine canyons are dominant features of the outer continental shelf and slope of the US East coast from Cape Hatteras to the Gulf of Maine. There are 13 major canyons in the Middle Atlantic Bight (MAB) region, and minor canyons are abundant. The canyons vary in size, shape, and morphological complexity; some were scoured by the flow of rivers during past low sea level periods, but most formed via other erosional processes, such as mud-slides, debris flows, and turbidity currents. Cutting deeply into the bottom and linking the shelf to the deep sea, these conduits funnel man-made pollutants, organic carbon, and sediments from shallow to deeper waters. The most southerly of these canyons (just north of Cape Hatteras) occur in an extremely dynamic and productive area known as The Point (See map Figure). The Point has been characterized as one of the hottest fishing spots on the east coast, apparently fueled by upwelling generated by the collision of several major currents over complex bottom topography. Further north, large canyons (e.g., Norfolk, Baltimore, Washington, Hudson, Lydonia) occur at regular intervals. The canyons between Cape Hatteras and Cape Cod are less well known than those further north, and yet these are the subject of potential oil exploration and intensive fisheries.

Wolf eelpouts and brittle starfish. Image courtesy of Steve W. Ross, UNC-W. Download image (jpg, 55 KB).

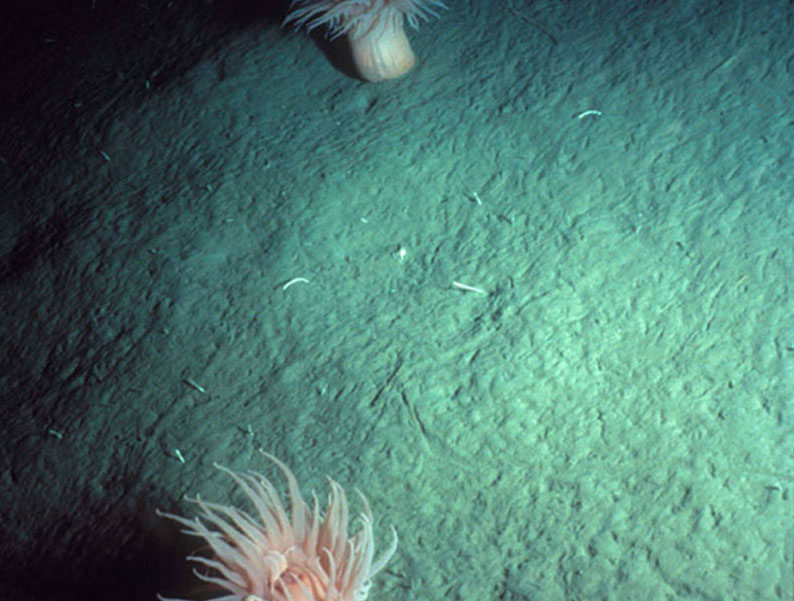

Cerianthid anemones on mud bottom. Image courtesy of Steve W. Ross, UNC-W. Download image (jpg, 105 KB).

The geology of these features has been well studied; however, despite their well known biological productivity, biological data are limited (particularly deeper than 200 m). We know that vulnerable and productive habitats, such as deep-sea corals and hydrocarbon seeps, occur in and around some of these canyons, yet these habitats are poorly explored. With a few exceptions, canyon communities differ in species composition from those in similar depths outside canyon influence. Larger animals are often more abundant in canyons at all depths, but faunal diversity increases with depth. These phenomena may be driven by entrainment of nutrient-rich sediments and organic material into canyons, enhancing food availability in a normally food poor area. Canyons represent areas of high biomass (including commercial fisheries) in the deep sea.

Canyons vary in physical structure, hydrography and geological activity, and this variation creates complex patterns in oxygen, temperature, food, sedimentation, and substrata. Exposed hard substrata are common in canyons and are generally found on the upper rims, where currents are elevated, and sometimes in the base of the axis, where boulders have been deposited. They may also occur on outcrops or relict shorelines along canyon walls, where currents keep substrata clear of sediment. Hard substrata often support dense communities of sessile suspension and filter feeders, such as cnidarians and sponges, which provide habitat for diverse and abundant faunal assemblages. Extensive holes and tunnels occur in various locations and depths in most Middle Atlantic canyons, and are inhabited by a number of other species; these excavations are created primarily by red crabs (Chaceon quinquedens) and tilefish (Lopholatilus chamaeloenticeps). In soft sediments, dense aggregations of sessile benthic animals, such as sea pens (pennatulids) and burrowing cerianthid anemones, create habitat for other animals (see Figures).

Soft sediments within canyons also support abundant mobile fauna. The motile invertebrate canyon fauna are dominated by echinoderms (sea cucumbers, sea urchins, brittlestars and sea stars), many of which feed on organic material deposited in the sediment. These taxa are often found in great numbers in soft sediments of the deep sea. As echinoderms are generally broadcast spawners, aggregation behavior may be a strategy to increase fertilization success.

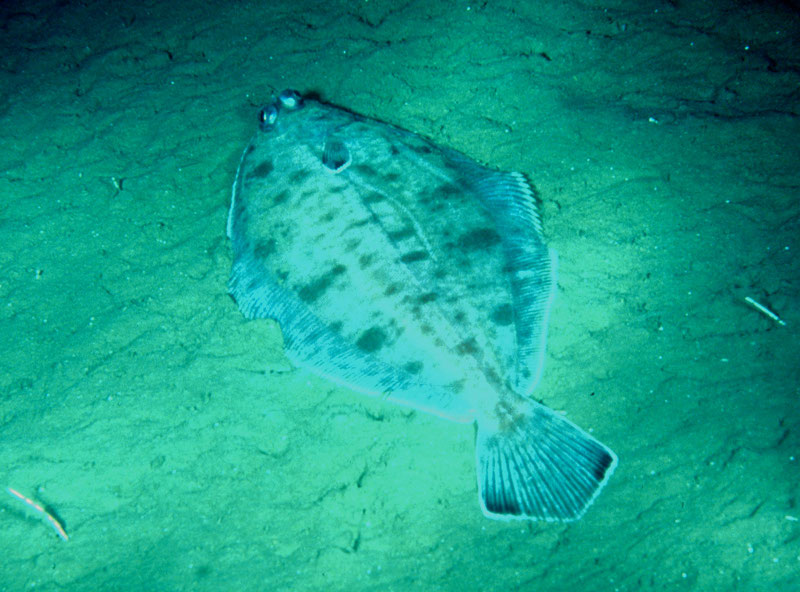

Witch flounder. Image courtesy of Steve W. Ross, UNC-W. Download image (jpg, 112 KB).

Red crab near rock covered with anemones. Image courtesy of Steve W. Ross, UNC-W. Download image (jpg, 78 KB).

As with invertebrates, bottom fish species appear to be more abundant in canyons than on inter-canyon slope areas of the same depth. For the Middle Atlantic, the dominant bottom fishes in canyons are often different from the open slope. The most common fishes are the eelpouts, witch flounder, Atlantic hagfish and grenadiers. These species feed on small prey, such as worms, crustaceans, brittlestars or plankton. Observed differences between canyons and adjacent slope may be explained by the food-entraining phenomenon associated with canyons. Midwater communities are also affected by submarine canyons, and they may impinge on the bottom, become entrapped, or may exhibit enhanced abundances in canyons.

These canyon ecosystems are important targets of study for the following reasons:

Cerianthid anemones and codlings. Image courtesy of Steve W. Ross, UNC-W. Download image (jpg, 84 KB).

Sea pen and gorgonians. Image courtesy of Barbara Hecker, Hecker Consulting. Download image (jpg, 58 KB).