By Elizabeth Larcom, Graduate Student

and Charles Fisher, Principal Investigator - Pennsylvania State University

This image illustrates how scientist measure a coral for size and growth rate. First, the edges of a structure are identified (a) and then the coral is digitally measured in pixels from the edge of a structure to the tip of the colony (b). The structure of known diameter is measured in pixels and then pixels are converted into centimeters (c). Distance “b” is divided by the number of years the structure has been submerged to get colony growth rate in centimeters per year. Division of coral length by the total number of years a structure is submerged assumes that the coal settled immediately after the structure was put in place. Because the coral may have settled at a later date, growth rate estimates using this method are always minimum growth rates. Image courtesy of Lophelia II 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 58 KB).

Lophelia pertusa is a Scleractinian (hard/stony) coral found throughout the world’s ocean. Lophelia is only found in cold water, at temperatures of 12ºC (53.6ºF) and below. This coral often occurs at depths greater than 200 meters (656 feet) down to over 2,000 meters (6,562 feet). Lophelia colonies often serve as habitat for numerous other organisms. As we are learning more about the distribution of Lophelia, we are also curious about its life history, including how fast it grows and how big it can get.

Life is said to move slowly in the deep and this often means organisms have slower growth rates and live longer than their shallow-water counterparts. Living over 2,000 years, deep-water black corals are among the oldest living organisms on Earth. They also grow very slowly at rates that can be lower than 8 micrometers (3.15x10-7 inches) in diameter per year.

Unlike most shallow-water corals, deep-water corals, including Lohpelia, do not contain photosynthesizing symbionts which contribute nutrition to growth. Despite this, and unlike most other deep-water corals, Lophelia appears to have growth rates that can be as high as some shallow-water coral species.

Other Techniques to Measure Growth Rates

The natural, deep, cold-water environment of Lophelia makes direct, continual monitoring and measurement of growth difficult. Scientists therefore use numerous and varied techniques to estimate the growth rate of Lophelia. Each technique has its unique advantages.

One method to measure growth looks at the amount of stable carbon and an oxygen isotope incorporated into coral tissues. This method has given growth rate ranges of 0.6-2.5 centimeters (0.24-0.98 inches) per year.

Sandra Brooke and Craig M. Young measured growth rates by collecting samples of Lophelia from the Gulf, staining them with Alizarin Red, returning them to the sea floor, and recollecting the same samples a year later. They measured growth rates to be approximately 2.44 millimeters (0.1 inch) per year, the slowest measurement obtained using any method.

Lophelia growth can also be measured in aquaria and studies show growth rates in the range of 0.5 – 1.7 centimeters (0.2- 0.7 inches) per year.

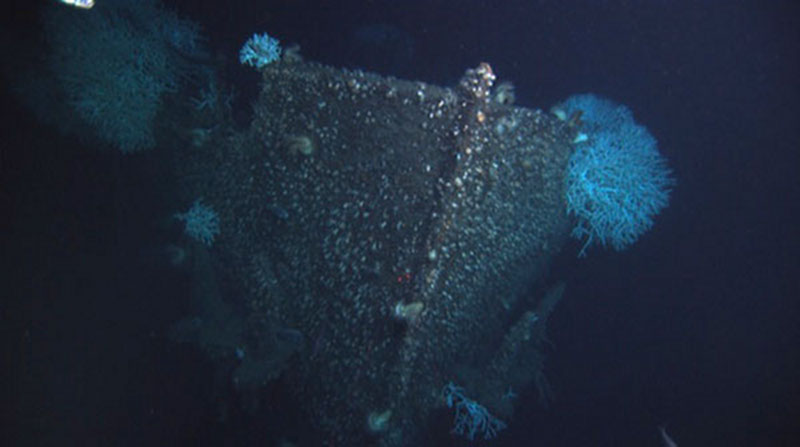

Another type of human-made structure that can be used to date and therefore provide maximum ages for corals are shipwrecks, like the Gulf Oil shipwreck pictured here, sunk by a German U-boat during World War II. Image courtesy of Lophelia II 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 41 KB).

One other technique to measure coral growth rates, and the method used on this cruise, involves the use of human-made structures to estimate how fast Lophelia grows.

Though an indirect method, artificial structures afford a non-invasive and non-destructive way to measure and monitor coral growth over time in their natural habitat. Under the proper environmental conditions, Lophelia appears to thrive on artificial objects and has been documented growing on structures ranging from trans-Atlantic cables to shipwrecks and oil platforms.

If the date of structure submergence is known, such as when a ship sank or an oil platform was set in place, we can use the current size of attached Lophelia to extrapolate how fast the coral has grown to reach its current size in the amount of time since the structure submerged.

In the past, measurements of Lophelia were taken from pieces of coral broken off of the structure. Now we can get coral size measurements from video or photographs with an object of known size or lasers for scale.

In a previous study, Susan Gass and J.Murray Roberts used inspection video from oil platforms and gas installations in the North Sea to measure Lophelia colonies. They calculated growth rates of around 2.5 centimeters (0.98 inches) per year. But these corals were not at deep-sea depths.

Using similar techniques, this cruise will mark the first time that Lophelia will be purposefully filmed for measurement of growth rates on oil platforms deeper than 200 meters (656 feet). We are excited to see how our findings at deeper water in the Gulf of Mexico compare to previous studies.