By Amanda W. J. Demopoulos - U.S. Geological Survey

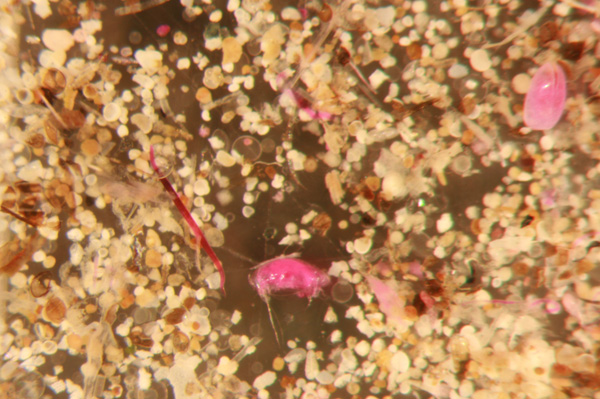

Examples of meiofauna present in the sediment. Organisms are stained using rose bengal prior to examination underneath a dissecting microscope. This sample contains ostracods, copepods, and nematodes. Image courtesy of Amanda Demopoulos, USGS. Download larger image (jpg, 1.2 MB).

Example of a tanaid discovered in a sediment sample. Image courtesy of Amanda Demopoulos, USGS. Download larger version (jpg, 883 KB).

Deep-sea corals are habitats rich with life, largely a result of the complex habitat that they generate. Fish and invertebrates are easy to see roaming within the coral environment, while much harder to see are the inconspicuous worms and crustaceans living within the cracks and crevices in the coral matrix and adjacent soft sediment (mud) environment.

While these small animals represent a significant portion of the biodiversity present within the deep sea, details of who lives there, their geographic range, and how similar these communities are to those found adjacent to human-made structures, such as oil platforms, and shipwrecks, remains a mystery.

The specific groups that my lab is interested in include the meiofauna (less than 0.3 millimeters) and macrofauna (greater than 0.3 millimeters). While they are practically invisible to the naked eye, these organisms play important ecological roles. They provide ecosystem functions, including serving as a food source for other animals. They can also alter the chemical environment through their movements in the sediment, similar to earthworms in garden soil, potentially making the sediment environment more hospitable to other species. Their long and stable lifespans and their vulnerability and quick response to disturbance make them useful indicators of stress and habitat health.

I’m interested in the biodiversity (who lives there) and food-web interactions (who is eating whom) of deep-sea coral ecosystems and how they relate to those found at shipwrecks and oil platforms.

Sieving push core material through a sieve to remove excess sediment before examining what fauna are present under the microscope. Image courtesy of Amanda Demopoulos, USGS. Download image (jpg, 73 KB).

In order to collect sediments from the oil platforms during this cruise, we will use push cores operated by the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Kraken II. A push core is a 50-centimeter (20-inch) clear plastic tube with a T-handle on top. The ROV grasps the T-handle and pushes the tube into the mud. Then the ROV pulls up on the T-handle and removes the tube from the sediment with a mud sample inside and returns the tube to the quiver on the ROV’s basket.

A successfully collected push core that has different sediment layers present. Image courtesy of Amanda Demopoulos, USGS. Download image (jpg, 179 KB).

When the ROV returns to the ship, the tubes are removed from the basket and placed into a cold (2°C, or 35ºF) room until they are processed. While still on the ship, each core is extruded on a plunger that pushes the mud to the top, the sediment is sliced into sections down to 10 centimeters (4 inches), and preserved for further processing. Back at the lab, the slices of mud are sieved through a screen to remove the mud and isolate the animals.

My lab will sort and identify the animals under a microscope. Typically, we find most of the animals within the upper 3 centimeters (1 inch) of sediment. Usually, this is because their food is more plentiful at the sediment surface and/or the sediment environment is often more hospitable in these surface layers.

The animals that we find come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Some have plates, like armor protecting their soft bodies, while others have various hairs and patterns that are unique to the species. In our collections thus far, we have found many animals that are similar to those associated with shallow-water tropical reefs, but very small in size. For example, we have found small sea urchins, tiny sea stars, small worms, and minute crabs in the sediments at the base of live coral.

In general, our results indicate that distinct communities of animals live in the sediments adjacent to natural coral reefs compared to non-coral, background soft sediments. However, we don’t know the scale at which these species turnover. In other words, we don’t know at what distance away from the reef the communities start to appear different.

Examining the sediment fauna found near oil platforms and shipwrecks will tell us if these artificial substrates function similarly to natural coral environments. We will be able to directly compare communities collected at the platforms to those previously collected at coral reefs and shipwrecks, and detect any differences in animal abundance and diversity between the natural and artificial substrates. In addition, sampling around the platforms will help us further identify the effect hard substrates have on communities in the surrounding sediments and if the patterns are similar on a regional scale.

By analyzing fauna from oil platforms, shipwrecks, and natural reefs, we will gain an appreciation for the species distribution around the Gulf and their association with hard substrates and understand succession over time scales of decades to thousands of years. The platforms that we will sample were established relatively recently (> 12 years) and provide us with a time point for identifying early colonists (who arrives first) in the sediments.

On previous cruises we sampled older shipwrecks (> 50 years), which provide us with another time window for understanding succession in these sediment communities. These new data will allow us to address questions of colonization and succession normally difficult to examine in the remote reaches of the deep sea.

It will be exciting to see what we discover from these collections near oil platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. Ultimately, the potential for discovering new species and enhancing our understanding of species interactions are high, given what little we know about these small animals living in the deep sea. Better understanding of their diversity, distribution, and connectivity will be useful for developing effective adaptive management and conservation strategies for vulnerable deep-reef ecosystems.