By Timothy M. Shank, Biology Department - Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

September 21, 2012

2125 GMT

Wind – SE @ 9 kts

Air Temperature – 26.3° C (78.8° F)

Sea State – 2.3m

A scale worm, only found at hydrothermal vent communities, imaged by the Quest 4000 at West Mata. Image courtesy of MARUM, University of Bremen and NOAA-Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory. Download larger version (jpg, 675 KB).

Open up any science textbook today and you will likely find a section dedicated to deep-sea hydrothermal vents, often regarded as one of the top 20 scientific discoveries of the 20th century. Amidst the definition of vents will be a description of their major characteristic - that they are transient and ephemeral. Vent systems in the deep sea have a birth, life, and death, in which vents are often created through volcanic activity and crustal cracking and often their cessation brought about by subsurface plumbing changes or through cooling of their heat source or magma chamber.

Vent-endemic animal communities rely on the chemicals in hydrothermal fluids and as such, are subjected to the creation, waning and dying of venting activity. Vent fauna are thus considered to be highly adapted to frequent and sometimes devastating disturbances, including rapid rates of growth to maturity, high fecundity, and a high frequency reproductive output to provide the best chance of colonizing distant or recently created vents, and maintaining their species.

A large crab of the genus, Paralomis, crawls on the volcanic sediment and rock at West Mata. Image courtesy of MARUM, University of Bremen and NOAA-Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory. Download larger version (jpg, 628 KB).

In 2009, the first ROV dives at West Mata Volcano discovered active volcanic activity and hydrothermal venting associated with primarily two vents on the central promontory: Hades and Prometheus, from which explosive activity and lava fragmentation, high-temperature venting, and lava flowing downslope were observed. Near these explosive vents on the crest of the volcano, there was a notable absence of macrofauna. The active and ongoing creation of new seafloor via volcanic activity may have prevented the colonization of sessile and mobile fauna. Interestingly, the diffuse venting fluids (~5 to 25°C), issuing through cracks and crevices ~15 to 40 m from the vents, played host to only one type of vent fauna – alvinocarid shrimp. This shrimp, confirmed later via genetic analysis to be Opaepele loihi (pronounced "o-pay-pay-lay low-ee-hee"), the same species as those inhabiting Mariana seamounts north of Guam and Loihi Seamount off eastern Hawaii. The shrimp were abundant (near 100 per m2) and were grazing on microbes (confirmed from later isotope analyses) growing on rock surfaces bathed in the clear diffuse venting fluids. Several zoarcid eelpout fish were documented within 40 meters of these main vents. The only fauna attached to the seafloor were observed far away from the explosive vents - as much as ~450m. These included a clump of “non-vent“ stalked barnacles and a single deep-sea coral.

The opportunity for repeat visits to seamount vents to document changes in the hydrothermal vent communities and habitat water chemistry as we are doing here is rare and fortuitous for the biologist to try to understand how vent communities respond and how resilient they are to disturbances. This knowledge is particularly important given the increasing interest in mining hydrothermal vent fields, both active and inactive ones, that may cause disturbances. Other post-eruptive vent sites have seen a return to mature pre-eruption communities of tubeworms and other worms, crabs, mussels, gastropod snails, and amphipods in just three to four years. At West Mata, what animals might have colonized these vents? Would we see bushes of tubeworms, fields of mussels, chimneys with snails and crabs, the like of which we know dominate the closest known vent sites on the adjacent spreading center in Lau Basin? Would we see no change at all? Perhaps continuing eruptions forming new seafloor would prohibit any potential colonizers from coming into the area. Shrimp as we saw them as the dominant fauna may be the steady state for this eruptive seamount. Lastly, perhaps completely unknown fauna might have arrived.

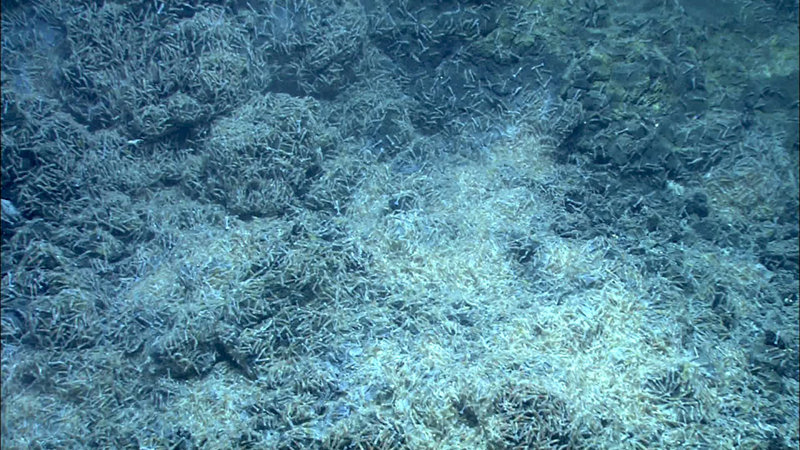

Opaepele shrimp were the only fauna (other than a single zoarcid fish) observed in May 2009 on West Mata, as shown in abundance here at Shrimp City. Temporal changes in vent community structure revealed a massive increase in the number of shrimp, as seen during this cruise near Shrimp City. Image courtesy of MARUM, University of Bremen and NOAA-Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory. Download larger version (jpg, 799 KB).

All of these possibilities were at the fore in our minds when we descended to the site for the first time after three years. Our immediate landing and approach gave us some clue when our dive started on the western flank at a place called Mat Meadow, a mounded area covered with extensive white microbial mats in 2009. Now the site is covered in rust colored mats and sediments, and we saw hundreds of polychaete worms swimming above the seafloor by undulating in the water column, zoarcid eelpout fish of two sizes, and polynoid or scales worms were scouring the rocks. Nearby, we came upon the “Luo“ site to discover it was still venting but less vigorously. As in 2009, white shrimp were here, yet much less abundant. As we moved to the east along a fissure, we found more venting with red scale worms, large zoarcid fish, more white shrimp, squat lobster crabs, and large (“square headed“) Paralomis crabs amidst dark volcanic sediments and rocks. We arrived at the site where in 2009 the explosive Hades vent was erupting lava, building up the seafloor. Where Hades once stood tall, there was a deep pit active with venting. Hades Pit was teeming with shrimp, two species now, the white Opaepele-type and also a larger shrimp with two well-defined eye stalks (unlike Opaepele) resembling those observed in the Lau Basin. This shrimp was actively feeding on other shrimp. Zoarcid fish (at least 35 observed) and inch-long red worms inhabited the Hades Pit site. The abundance of shrimp in this area more than tripled the highest density observed in 2009. As the dive progressed, we reached a site we called “Shrimp City“ in 2009 due to this area hosting the highest density of shrimp. The Opaepele shrimp were again still here, but in an abundance that completely covered meters of seafloor. So numerous were these shrimp bathed in shimmering vent water that preliminary estimates suggest that their density is likely the highest of any shrimp clustered at a diffuse flow vent site, perhaps more than 1000 per m2, second to only the density of Rimicaris shrimp (at 2500 individuals per m2) observed on the sides of Atlantic and Central Indian black smokers.

In the end, while the eruptive activity has at least temporarily ceased at West Mata, the existence and persistence of hydrothermal habitats and the development of the hydrothermal vent communities continues. Polychaete worms (at least three species), shrimp (two species), crabs (three species) and other grazers on microbial material, as well as predators, such as the zoarcid fish, are increasing the number from two species in 2009 to at least 13 (at all trophic levels on West Mata). Mobile fauna continue to dominate the vents at this seamount. However, the several mobile species, including giant snails known from the region, have not previously been observed here. Sessile fauna, such as tubeworms or stalked barnacles, that we know to be in the thousands covering massive sulfide pillars at seamount vents just 20km from West Mata, have similarly not been observed… yet.