By Chris German, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

April 25, 2012

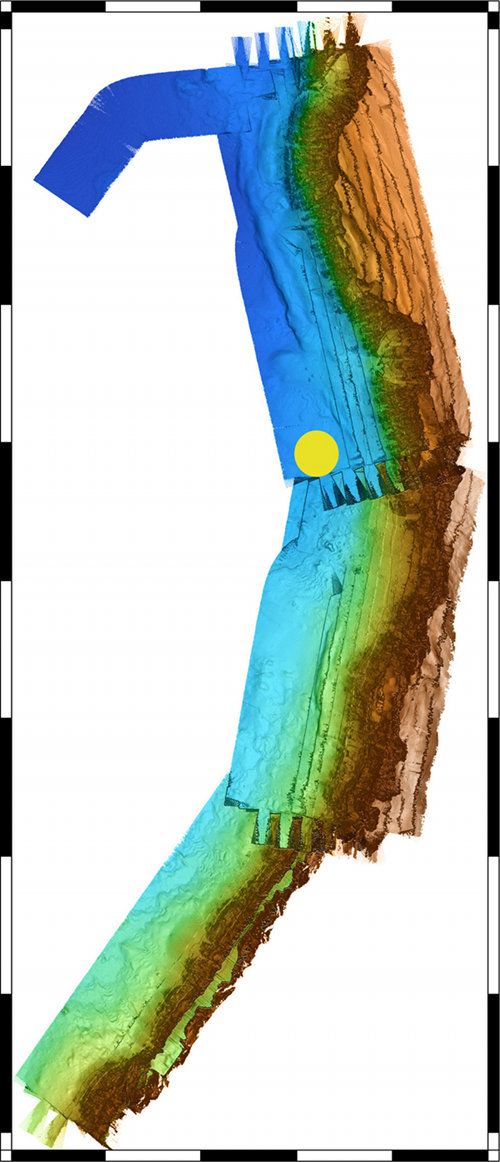

Here’s the map that Sentry made overnight – or rather, the first-cut version of the map that Dana made after lunch today using the data acquired by Sentry overnight. This is by no means the final version, but it is good enough for us to plan our follow-on surveys and certainly shows we have all the data that we wanted to collect. Image courtesy of Chris German, INSPIRE: Chile Margin 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 114 KB).

Yesterday was a challenging day. TowCam had some gremlins that required a change of plan, so my cabin-mate Tim came and fetched me out of my bunk at 6:30 am to start planning the next Sentry dive. We planned to make detailed maps of the cliffs that mark the transition from the mid-ocean ridge to the continental margin here at the Chile Triple Junction, together with the next CTD cast that was designed to tow along the base of that same cliff, sniffing for methane anomalies by tripping bottles and passing them to Marv. All was ready to go by late morning, and Sentry was in the water right before lunch. Then Sentry was back out of the water with its own gremlins right after lunch.

After some issues, it was back in the water just in time for dinner. Right around the same time, the TowCam engineers, Greg and John, had problems with the camera straightened out and completed a quick dip-test to make sure all was well before we sent them and Tim off to bed (they had all been up all night and day by this point). We ran our long-awaited, now 10-hour-overdue, CTD cast. That ran until 3 am, and by 5 am we had the samples taken and Marv geared up to run his methane analyses.

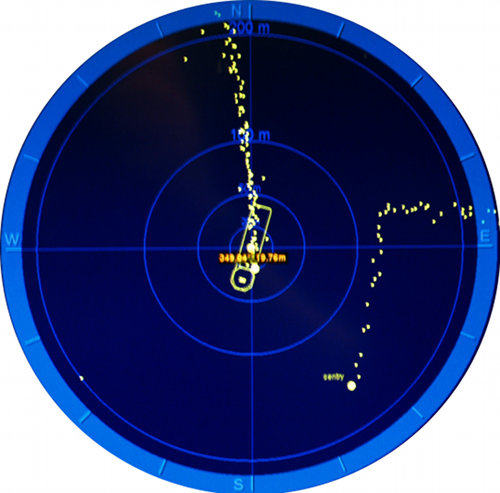

Right around midnight, the last thing I had seen was the display on our navigation beacon where Sentry had flown to within 100 meters of our CTD's position, dangling under the ship, while we waited for it to swim by underneath us for 10-15 minutes and then resumed our own survey. With only two pieces of scientific equipment in the deep ocean for probably hundreds of miles around here, the last thing we want to do is cause a crash!

By the time I got back up for a science team meeting this morning, we had just completed our first successful tow with the camera system and Sentry had also finished its mapping mission and was on its way home from the seabed. With the data Sentry collected, we have now been able to generate a first-draft map of the seafloor all around the cliff face most of interest to us, and we are now conducting a final long CTD deployment as both Sentry and TowCam recharge their batteries to be ready to get back to work overnight.

Air traffic control, 3,000 meters below sea level. This shows a zoom in of our navigation screens from around midnight last night when Sentry, operating in the top left corner of the middle block of data it collected in the previous image, flew directly beneath the CTD and ship that were heading due south. Image courtesy of Chris German, INSPIRE: Chile Margin 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

Here, with the final 1.5 days of our 4.5 days on station remaining, is where we make a transition in the emphasis of our multi-disciplinary science program. Thus far we have emphasized a roughly equal mix of understanding the solid Earth processes at the Chile Triple Junction using our sidescan sonar and multibeam mapping sonars on Sentry. In parallel, we have been studying the overlying ocean using our CTD in a series of extensive deployments. While we have also been trying (but with a disappointing lack of success) to get some first samples from the seafloor, now is when our biological goals come into sharper focus. Sentry is being reprogrammed to head back to the seafloor and take near-bottom photographs to find what might be living down there, throughout the area we have now mapped very precisely with Sentry. TowCam is also being readied for two or more specific tows within the remaining time available.

One of our key targets is the area where two sediment multi-core samples in our 2010 cruise brought up sediments that were anomalously warm compared to the overlying deep ocean and which, subsequent analyses revealed, indicate animals living on a chemosynthetic (perhaps hydrothermal?) diet.

Sentry engineers Andy (left) and Justin (right) making final preparations to Sentry out on deck, ready for deployment. Image courtesy of Chris German, INSPIRE: Chile Margin 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download larger version (jpg, 2.3 MB).

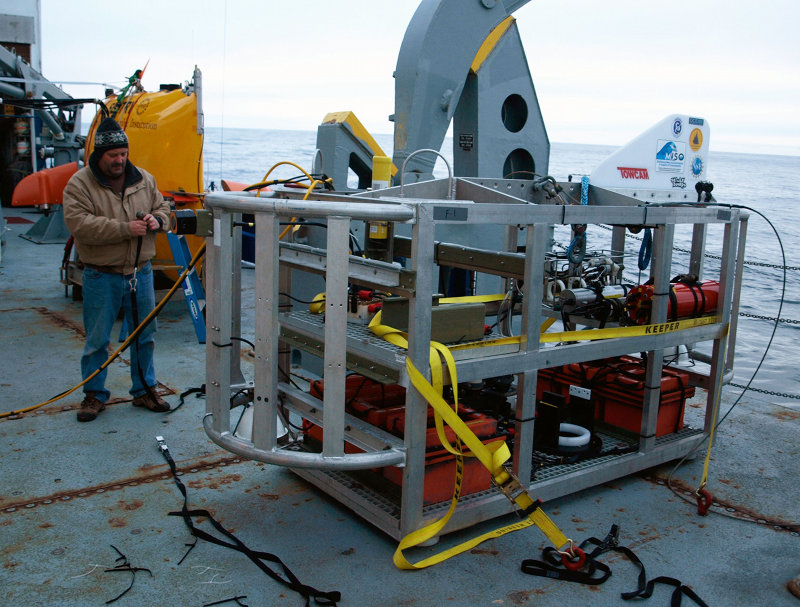

TowCam engineer John making similar final preparations for TowCam. As soon as Sentry is overboard tonight, TowCam will follow fast behind, surveying a different part of the seabed and sending images straight back to the operators aboard ship while Sentry stores its photos onboard its own computers to await return to the ocean surface on Friday. Image courtesy of Chris German, INSPIRE: Chile Margin 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download larger version (jpg, 2.2 MB).

Another target for TowCam – of interest to the chemists aboard ship as well as the biologists – is to conduct a hill climb right up the cliff face, following the direction along which the Chile Rise disappears under the South American continent. And the final target is a mystery "jelly-like blob" (at least that's my formal scientific term) that showed up in the sidescan sonar on our first Sentry dive and looks for all the world like something that has flowed out over an area about 100 meters in diameter over the sediments a mile or more north of the Triple Junction along the line where the Mid-Ocean Ridge should lie, buried in soft sediment.

We have no guarantee that we know what this feature really represents, nor what might be down there. But we DO know that those data, collected over one five-minute window in over 10 hours of survey on bottom, looks unlike anything else we recorded throughout that dive; it is out on the ridge-axis in the general vicinity of where a second set of chemical anomalies are seen. In the true spirit of ocean exploration, we figure we'd better take a look at what geologic processes are happening down there, whether there are any fluids escaping into the ocean, and how the animals living in this environment compare to the normal animals (which we also get to learn about from Sentry's larger mission over the next day or so) that inhabit this previously unstudied part of the ocean floor.

So, starting right now, we're finally in a position (remembering that we started proposing this work in 2003 and were already here in 2010 putting in the legwork that got us this far) to head down to the seabed with all camera systems flashing to investigate the geology, oceanography, and biology in this unique part of the planet.

So...Earth, oceans, and life. I think that's the basics covered.

Check back in soon to see what we find out!