By Russ Hopcroft - University of Tromsø, Norway

September 9, 2012

Rinsing of a newly collected zooplankton sample. Image courtesy of Kate Stafford, 2012 RUSALCA Expedition, RAS-NOAA. Download image (jpg, 65 KB).

During the Russian-American Long-term Census of the Arctic 2012 cruise, our four-person team (Ershova, Hopcroft, Kosobokova, Rutzen) is studying the distribution of the small animals that drift within the water called zooplankton.

The butterfly net for zooplankton being deployed over the side of the Khromov. Image courtesy of Kate Stafford, 2012 RUSALCA Expedition, RAS-NOAA. Download image (jpg, 60 KB).

It has been a surprisingly uneven cruise for zooplankton studies. Accustomed to getting samples with our elaborate “butterfly-nets” almost as frequently as the CTD is deployed, we were routinely being shut down by weather. We didn’t give up gracefully. At the last station where we pushed our limits, the twin-ring nets – hung from a frame resembling a pair of wire-rim glasses – returned bent back nearly 90 degrees on the towing yoke. The ties holding the nets to the frames had been popped off, like buttons on a snagged shirt. They were saved only by the stainless steel shackles used to mount small distance-measuring propellers within them.

How could this happen? Our nets are designed for vertical operation, weighted by about 100 pounds of chain and iron. But when the wind is high, the Khromov becomes a sail on the ocean’s surface. Our nets had been strung out almost horizontally by the rapidly drifting ship and dragged harder than their design tolerated. So we waited and waited for the weather to improve, yet it only got worse. Finally, we headed northward seeking shelter in the ice-covered waters.

Liza Ershova selecting individual copepods. Image courtesy of Kate Stafford, 2012 RUSALCA Expedition, RAS-NOAA. Download image (jpg, 54 KB).

Ksenia Kosobokova looking for gravid female copepods for egg production experiements. Image courtesy of Kate Stafford, 2012 RUSALCA Expedition, RAS-NOAA. Download image (jpg, 50 KB).

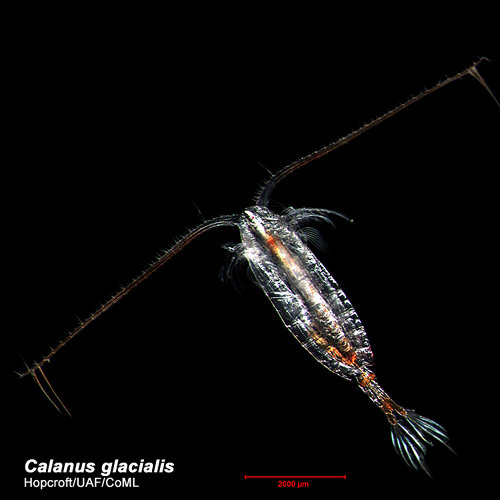

Nearer to Wrangel Island, above the Siberian Coast, the sea-ice began to dampen out the swell, and the wind began to abate. Sampling was once again possible. The plankton community here has lost much of the Sub-arctic Pacific character of the more southern stations, and is now dominated by Arctic species – especially the copepod Calanus glacialis.

The contrasts we observe across the 50-mile wide Herald Valley transect have been quite remarkable. In the east, we detect traces of sub-Arctic Pacific species, and huge populations of ctenophores – a jellyfish cousin – that are gorging on the herbivorous zooplankton.

The copepod, Calanus glacialis. Image courtesy of Russ Hopcroft. Download larger version (jpg, 142 KB).

Although often important elements in the plankton communities, ctenophores are poorly quantified in most studies because they disintegrate after death rather than preserve like other zooplankton. At each station, we sort through fresh samples counting, measuring, and removing the ctenophores before they turn our preserved sample to goo. In several bongo-net samples, we removed over 200 ctenophores – roughly two per cubic meter of water.

As we move west and the northward, the larvaceans – sea-tadpoles – and the ubiquitous Calanus dominate the samples, and midwater temperature drops from ~4°C to -1°C. We are now effectively working around the clock collecting samples to preserve, identifying jelly-plankton, and sorting fresh samples for Liza Ershova’s egg production experiments.

Algal blooms stimulated by the recent breakup of the sea-ice, along with the mucus build-up larvacean feeding structures and damaged ctenophores, clog our nets and make cleaning them a slow process. We preserve in the near-freezing temperatures.

Unexpectedly, we have been treated to several windless days with glass-like seas and even sunshine – for that we are thankful after the far less-pleasant weather in which we began two weeks ago.