By Bodil Bluhm, Research Associate Professor in Marine Biology and Biological Oceanography - University of Alaska Fairbanks

and Katrin Iken, Associate Professor in Marine Biology - School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, University of Alaska Fairbanks

September 2, 2012

Treasure trawled up from the seafloor during the second leg of the RUSALCA 2012 expedition. Image courtesy of Katrin Iken, 2012 RUSALCA Expedition, RAS-NOAA. Download image (jpg, 170 KB).

We like to think the trawl is the most popular gear during most cruises. Anyone from kitchen staff to cleaning personnel, winch operator to our fellow scientists, including even the geologists and ‘clean water’ colleagues come to take curious peaks when we empty out the trawl net and spread out the treasures from the seafloor in sorting dishes on deck. And colorful the catches are: purple and yellow sea stars, red and white striped shrimps, pink anemones, iridescent snails and orange crabs. Some are beautiful like the slender Plicifusus snails with elaborate sculptures, some are fierce-looking like the Spirontocaris shrimps with sharp claws and spines, some are unappetizing like the gelatinous glob sea cucumbers Myriotrochus, and some are plain weird like the long stringy rubber band moss animals Alcyonidium.

Trawl samples are divided by taxonomy. Image courtesy of Katrin Iken. Image courtesy of Katrin Iken, 2012 RUSALCA Expedition, RAS-NOAA. Download image (jpg, 117 KB).

While some of the by-standers picture part of the haul in the frying pan, maybe juicy shrimps in garlic sauce or snails in wine sauce, we sort, count, and weigh every little critter to quantify the epibenthic community, meaning the larger seafloor dwellers that inhabit the sediment surface. These partly mobile, partly sessile (attached and not moving far) invertebrates contribute to the high benthic biomass here in the southern Chukchi Sea.

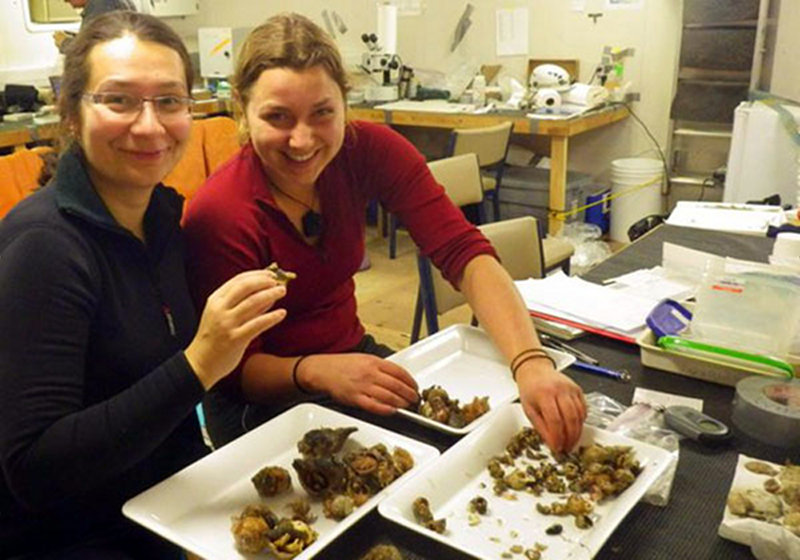

Lauren Bell and Bodil Bluhm sifting through a sediment grab. Image courtesy of Katrin Iken, 2012 RUSALCA Expedition, RAS-NOAA. Download image (jpg, 114 KB).

Some are food for fishes, walrus, bearded seals, and gray whales and are a reason for their plentiful abundance in the region in the summer. But we wonder what effects the much debated climate change may have on the epifauna over time in the Chukchi Sea. We will not know the answer until we have a time series, or repeated observations of the seafloor fauna over several years to observe any potential changes.

Unlike temperature, salinity, and other water properties that can be measured efficiently with automated long-term moorings and quick Conductivity-Temperature-Depth (CTD) casts, sampling seafloor communities still takes people on ships, counting and identifying each animal by hand. It is an expensive endeavor, but building a time series of the Chukchi Sea fauna is part of the mission of the Russian-American Long-term Census of the Arctic (RUSALCA) program and, therefore, of this cruise.

We are now just above 68 degrees North and 166 degrees West with Point Hope on the Alaskan coast in sight. Caught between two typhoon storms and their windy and wavy consequences in the Chukchi Sea, we manage to squeeze in a time-series station, and drop our net right where we already sampled in 2004 and 2009.

Monica Kedra and Lauren Bell working with trawl samples in the lab. Image courtesy of Katrin Iken, 2012 RUSALCA Expedition, RAS-NOAA. Download image (jpg, 109 KB).

Dressed in mustang overalls, steel-toe boots, and lined rubber gloves with hard hats on our heads, we get tubs and buckets ready for the incoming haul. The winch man pulls in several hundred feet of wire, then it is time for us to pull the net in with its metal beam, sturdy floats and iron weights - and its precious content - over the stern by hand. Untie that knot that holds the cod end together, and out pour Arctic cod and staghorn sculpins, snail fishes and eel blennies.

But, like elsewhere in the high Arctic, these mostly small fishes are overwhelmingly dominated by invertebrates: hermit crabs, crabs and shrimps, sea stars, brittle and basket stars, snails, and sea squirts. We are delighted to have this valuable sample in hand, and just an hour or two later, the storm has us back, big breakers wash over the deck making more sampling impossible for the next few hours.