By Jeffrey B. Glover, PhD, Assistant Professor - Department of Anthropology, Georgia State University

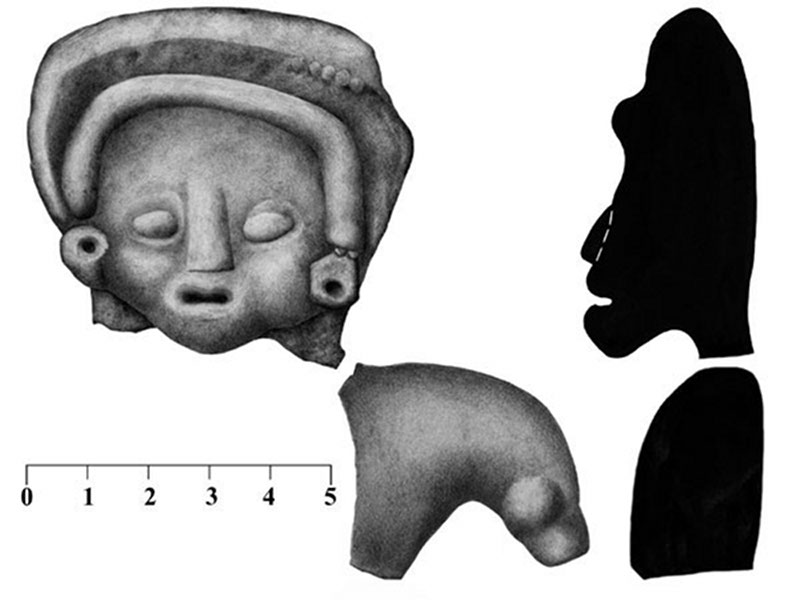

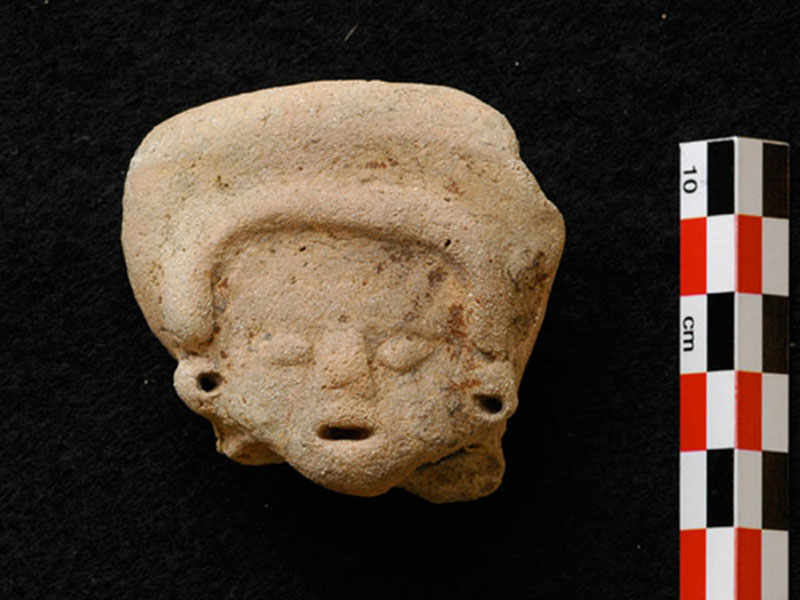

A fragment of a Middle Preclassic figurine that was recovered in 2008. Members of the PCE dated the figurine to the Middle Preclassic (c. 800 – 600 B.C.) based on stylistic characteristics. This figurine probably arrived with the island’s first permanent inhabitants. Image courtesy of Jennifer Taschek, Proyecto Costa Escondida Maritime Maya 2011 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download larger version (jpg, 1.8 MB).

The preliminary archaeological fieldwork and ceramic analysis conducted by the Proyecto Costa Escondida (PDE) has revealed four major periods of occupation at the site ranging from the Middle Preclassic period (c. 800-400 B.C.) to the Postclassic (A.D. 1100-1521). The site, however, was not continuously occupied, nor did the function of the port remain constant through time. In the Maya area, and Mesoamerica more broadly, the analysis of the stylistic attributes (i.e. designs, slips and forms) of ceramics is key for chronology building. The ceramic data provide a relative chronology that is then pegged to our calendar through radiocarbon dates or their association with monuments with datable inscriptions. Where contexts are not stratified and associated with carbonized remains or are not associated with datable inscriptions, ceramic cross-dating is the norm and that is how we determined the dates below. In addition to being chronologically sensitive, attributes associated with paste, form, and surface decoration of ceramic vessels are key for interpreting interregional interaction and cultural affiliation, when combined with other architectural or artifactual datasets.

Vista Alegre I (800/700 - 450/400 B.C.) – The First Settlers

A fragment of a Middle Preclassic figurine that was recovered in 2008. Image courtesy of Proyecto Costa Escondida Maritime Maya 2011 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 81 KB).

A large Caroline Bichrome sherd (rim, neck, and shoulder of large vase). The Carolina ceramic group was one of the most popular in the Yalahau region, the mainland area to the south of Vista Alegre, during the Terminal Preclassic period (75 BC to AD 400). Image courtesy of Proyecto Costa Escondida Maritime Maya 2011 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download larger version (jpg, 211 KB).

The first pottery using people arrived at the island between 800 and 700 B.C (the Middle Preclassic period). What is most surprising is that these people brought with them material culture (i.e. pottery and figurines) not associated with the northern Yucatan peninsula (the northern Maya lowlands) but more closely aligned with the eastern Petén-Belize area located far to the south. Most striking was the discovery of a figurine head, the first of its kind from the northern Maya lowlands. These figurines were traditionally used in household ritual contexts and do not seem to be trade items during this time period. The figurine, along with the other ceramic data, pushes our estimation of the initial settlement of the region back by as much as 150 years.

Vista Alegre IIa (A.D. 100/150 - 400/450) – Yalahau Connections

After an apparent hiatus, it is clear that there was a bustling settlement at the site during the Vista Alegre IIa period. This is not surprising given the dense inland populations at this time. While it is clear that people at the site were interacting with inland populations given the broadly shared use of Carolina, Sierra, and Tancah ceramics (the three dominant groups found at inland Yalahau sites during this time period), these people were also part of broader interaction networks, typical of coastal settlements.

Vista Alegre IIb (A.D. 400/450 - 650) – Coastal Resilience

The continued occupation of Vista Alegre is evidenced by the continued presence of certain ceramic groups along with trade wares from the western and southern lowlands. This was not the case at the inland Yalahau sites, which witnessed a major depopulation sometime during the 4th or 5th century AD. Based on the analysis, the later materials are present in lower percentages than the earlier materials and indicate the possibility of a declining on-site population. The site appears to have been abandoned by A.D. 650 at the latest. As work continues at the site, it will be interesting to further document how life continued on the island, possibly for a couple of centuries, in the absence of surrounding populations.

Vista Alegre III (A.D. 850/900 - 1100) – Itzá Influence

Sherds of Balantun Black on Slate. This ceramic type with the black trickle design was a common domestic ware during the Terminal Classic at Chichén Itzá (AD 900 – 1100). Image courtesy of Proyecto Costa Escondida Maritime Maya 2011 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

A close-up of two of Balantun sherds. Image courtesy of Proyecto Costa Escondida Maritime Maya 2011 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download larger version (jpg, 2.1 MB).

After an apparent hiatus of around two hundred years, a group of people resettled the island during the Terminal Classic period. But, who were these people, where did they come from, and how did they articulate with the burgeoning circum-peninsular trade networks? The preliminary data provide some clues to these questions but raise many more.

We know from previous research that control of portions of Yucatan’s north and east coasts was critical to Chichén Itzá's rise to prominence in the Terminal Classic, as it allowed the site to become a major player in the circum-peninsular trade routes that ran from Veracruz down to the Gulf of Honduras. Archaeologists have used the presence of ceramic types ascribed to the Sotuta sphere, green obsidian from the Pachuca source in Hidalgo, Mexico, and certain iconographic and architectural elements to infer Chichén’s control over a site.

Given the particular assemblage at Vista Alegre, a strong connection with the Itzá is clear. When a non-local ware appears as the domestic utility ware (in this case the ceramic type Balantun Black-on-slate) at a site during a time when there appears to be few if any local people living in the area, then we feel confident in concluding that actual people with close ties to Chichén were the ones who resettled the island during Vista Alegre III times. This argument is bolstered when the other Sotuta ceramic materials (Silho, Tohil, and Dzitas groups) are taken into consideration along with our preliminary obsidian data. We have not only recovered more obsidian than all of the interior sites combined, but we have the only examples of Pachuca obsidian (14% of our sample) in the area.

While the initial repopulation of the island is an interesting question, it is only one component of our research that endeavors to better understand what life was like for the inhabitants of this coastal port during the Terminal Classic. Regardless of who resettled the island, it is clear that the community was integrated into the political economic network centered at the Itzá capital. The future research strives to provide insight into Chichén’s expansionistic strategies, how these either took advantage of or repressed the growing entrepreneurial spirit emerging along the coast during the Terminal Classic, and eventually failed (as evidenced by our Vista Alegre IV materials).

Vista Alegre IV (A.D. 1100 – 1521) – Pilgrimage Locale

Vista Alegre appears to have been abandoned by its residential population at the close of the Terminal Classic or early portion of the Postclassic period. Although abandoned, the site maintained its ritual significance for coastal inhabitants and traders as evidenced by the pilgrimage ceramic assemblage (Chen Mul modeled incensario fragments and Payil Red vessels) and the presence of the carved serpent-head balustrade.

We know that traders visited coastal shrines as they made their way around the Peninsula. Did Vista Alegre become one such large shrine site, an important part of the sacred landscape and a reminder to travelers of a haven that their ancestors once used? Or was the site more commonly visited by local populations who were making offerings to their past ancestors or deemed the site significant due to its past ties with the great city of Chichén Itzá? While these scenarios are purely speculative, an understanding of the spatial patterning of the Postclassic materials as well as looking at sources for the ceramics are two avenues of investigation that we hope to pursue to better understand Vista Alegre’s continued allure; while abandoned it was not forgotten.