By Tom Iliffe, Principal Investigator - Director, Marine Biospeleology Lab Texas A&M University

The subterranean aquatic environment consists of small (cracks in bedrock or gaps between sand and gravel particles) and large (cave) water-filled spaces. Underwater caves exist either in limestone (formed by dissolving of the rock by weakly acidic groundwater) or in lava (created as lava tubes during volcanic eruptions).

Clear, deep lake in Church Cave. Image courtesy of Bermuda Deep Water Caves 2011 Exploration, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 95 KB).

Since Bermuda is a relatively small island with no place very far from the sea, most of the island’s limestone caves contain clear, tidal pools in their interior (Fig. 1). The water in such underground environments can vary from completely fresh to fully marine salinity. These pools are the gateways to complex networks of underwater passages primarily at 18 m (60 ft.) depths and were probably formed by at relatively prolonged still stand of Ice Age sea level at this depth. The Bermuda cave habitat is characterized by the absence of light, a salinity and temperature stratified water column, very limited food resources, low levels of dissolved oxygen and stable environmental conditions. Similar to Bermuda’s water filled caves are cenotes in Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula and blue holes in the Bahamas and Belize. In addition, other such cave habitats, including limestone and volcanic caves, occur on islands or peninsulas around the Caribbean, Mediterranean and Indo-Pacific.

Ecologically, animals permanently living in underwater caves can be subdivided into stygobites (cave-adapted species restricted to subterranean waters) and stygophiles (species inhabiting caves and completing their entire life cycle there, but which also occur in similar open water habitats). The prefix "stygo" refers to the subterranean River Styx which from Greek mythology circles through Hades or the underworld. Thus, stygobites are literally the "aquatic cave life", while stygophiles are "aquatic cave lovers".

The mictacean Mictocaris halope, shown here as viewed through the scanning electron microscope, represents a new order of crustaceans known only from Bermuda caves. Image courtesy of Bermuda Deep Water Caves 2011 Exploration, NOAA-OER. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

Although cave-adapted animals have long been known and studied from freshwater caves, the discovery of similar animals from marine caves is a recent event brought to light by cave diving explorations. Anchialine (underground voids near the coast filled with tidal, brackish or marine water) caves typically possess surface layers of fresh or brackish water separated by a halocline from deeper, fully marine waters. Cave diving has been an essential tool to explore and study the deeper waters in such systems where most stygobitic animals live. Anchialine and freshwater stygobites are mostly crustaceans, and include several higher groups of crustaceans found only or primarily in subterranean habitats.

Cave copepods have lost their eyes and color. Image courtesy of Bermuda Deep Water Caves 2011 Exploration, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 105 KB).

The ostracod Spelaeoecia occurs in caves in Bermuda, the Bahamas, Cuba, Jamaica and Yucatan. Image courtesy of Bermuda Deep Water Caves 2011 Exploration, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 34 KB).

An extraordinarily rich and diverse group of cave adapted organisms inhabits the inland caves of Bermuda. Seventy-five cave limited species have been identified so far from Bermudian caves, including 64 crustaceans, 5 mites, 2 ciliates, 2 gastropod molluscs, and 2 segmented worms. In order of abundance, the crustaceans include 18 species of copepods, 18 ostracods, 7 amphipods, 6 shrimps, 6 cumaceans and 3 isopods. Notable in their absence are remipedes and thermosbaenaceans which are characteristic inhabitants of similar caves in the Bahamas and elsewhere in the Caribbean.

The mysid Bermudamysis is the sole member of this genus. It is found on the surface of silty sediments in several Bermuda caves. Image courtesy of Bermuda Deep Water Caves 2011 Exploration, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 55 KB).

The isopod Atlantasellus is the sole genus in a family first discovered from Bermuda. Image courtesy of Bermuda Deep Water Caves 2011 Exploration, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 38 KB).

Stygobitic animals from Bermuda caves include:

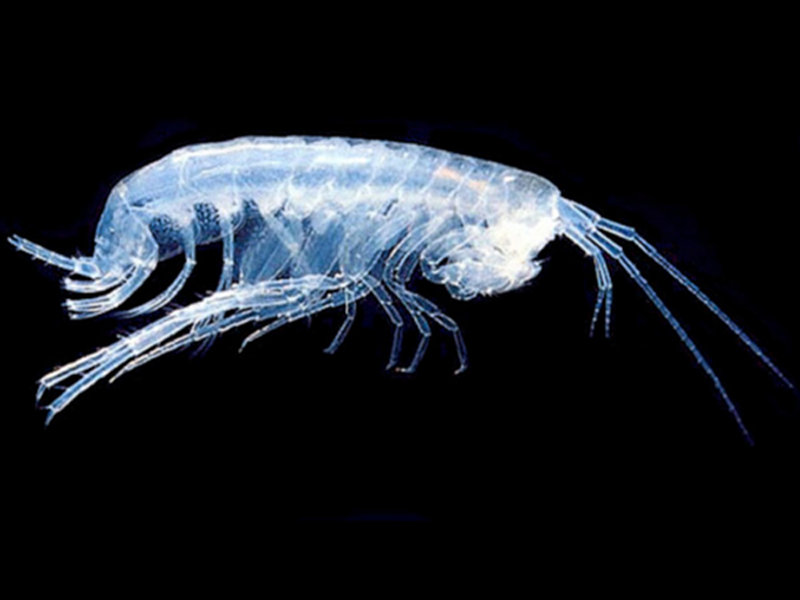

The amphipod Pseudoniphargus from Bermuda caves is eyeless and depigmented. Its closest relatives are found in caves and groundwater on the opposite side of the Atlantic and along the edge of the Mediterranean Sea. Image courtesy of Bermuda Deep Water Caves 2011 Exploration, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 48 KB).

The shrimp Bermudacaris has relatives from the waters off Western Australia and Viet Nam as well as caves in Mallorca. Image courtesy of Bermuda Deep Water Caves 2011 Exploration, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 28 KB).

Despite being limited to caves, many groups of anchialine organisms, such as many of those found in Bermuda, are widely separated, e.g., on opposite sides of oceans or even opposite sides of the Earth, and seemingly isolated from one another on a global scale. One theory attempts to explain such distributions by suggesting that cave organisms originated more that 200 million years ago when all continents were combined into one supercontinent and subsequently were dispersed by plate tectonic rafting as the continents separated and moved to their present positions. A number of other anchialine animals show close relationships with present deep-sea species implying a possible deep-sea origin for cave fauna. Finally, some cave animals are thought to have been 'stranded' in their present locations by receding waters of the Tethys Sea – the global sea at the time the continents were combined.

Rusting oil drum, some still with black residue inside, dumped in Bitumen Cave in Bermuda. Image courtesy of Bermuda Deep Water Caves 2011 Exploration, NOAA-OER. Download larger version (jpg, 3.4 MB).

Limestone quarry in Bermuda with remnant cave in center of cliff in the process of being destroyed. Image courtesy of Bermuda Deep Water Caves 2011 Exploration, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 117 KB).

Unfortunately, many of these unique and fascinating animals are threatened with extinction due to the actions of man. In Bermuda, 25 species of cave animals are internationally recognized as "critically endangered." This is the highest level of threat and roughly equates to a 50% chance of the species going extinct if nothing is done. All too frequently, anchialine cave animals can be considered endangered since they have very limited distributions, commonly being known only from a single cave, and environmental conditions in these caves are often deteriorating through the effects of water pollution or cave destruction.

Threats to caves include sewage and waste disposal, deep well injection, quarrying and construction activities and diver and other human disturbances. As an example, Bermuda is one of the ten most densely populated countries in the world and has the largest number of private cesspits per capita. Disposal of sewage and other waste water into cesspits or by pumping down boreholes is contaminating the ground and cave water with nitrates, detergents, toxic metals and pharmaceuticals, depleting the very limited amounts of dissolved oxygen in cave water, and generating toxic levels of hydrogen sulfide. Far too many caves and sinkholes are viewed as preferred locations for the dumping of garbage and other waste products (Fig. 9).

Another serious environmental problem concerns the destruction of caves by limestone quarries or construction activities. At least half a dozen or more caves have been destroyed by Bermuda limestone quarries which produce crushed aggregate for construction (Fig. 10). Many caves have been filled and built over by golf courses, hotels and housing developments in Bermuda. Recently, a series of luxury town homes were built directly on top of the largest cave lake in Bermuda.

Piles of copper coins from a wishing well pool in a Bermuda cave. Image courtesy of Bermuda Deep Water Caves 2011 Exploration, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 97 KB).

At least seven anchialine caves in Bermuda have been used commercial tourist attractions. Unfortunately, many of the tourists visiting these sites have viewed the deep clear water cave pools as natural wishing wells in which to throw a coin or two (Fig. 11). Copper coins tend to rapidly deteriorate and dissolve in salt water, producing high levels of toxic copper ions in the cave waters. It is time that visitors to caves begin to recognize these unique biological resources and take steps to make sure such rare ecosystems and organisms are protected for future generations.