By Charles Loeffler - Applied Research Laboratories, The University of Texas at Austin

The NOAA Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary is a large national sanctuary — 448 square miles (sq mi) — which includes all of Thunder Bay and a part of Lake Huron. It is the site of hundreds of well-preserved shipwrecks. The locations of numerous wrecks are known, but many others have yet to be found. NOAA is charged with maintaining and surveying this area, and they are always looking for new approaches to survey this large area with efficiency. The problem is compounded since the sanctuary may be expanded to over 2,000 sq mi.

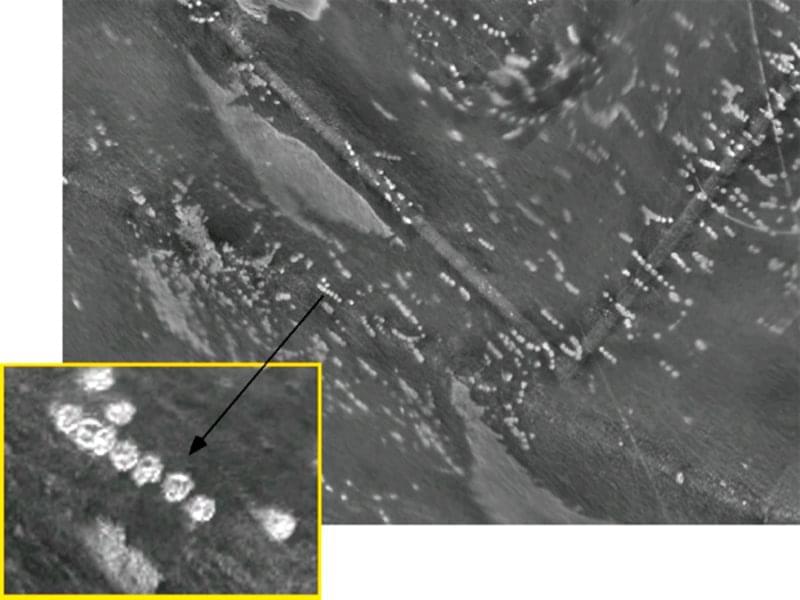

These piles dot the northern half of Thunder Bay near Alpena. Each circle is roughly 15 meters (49 feet) in diameter and some contain lumps of coal. Image courtesy of Thunder Bay 2010 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 51 KB).

Back in 2008, NOAA and the Applied Research Laboratories with the University of Texas at Austin (ARL:UT) felt that the ATLAS-AUV (autonomous underwater vehicle) would be a good sensor system to survey this area for known and unknown shipwrecks sites. Since the time when the project was originally proposed, Russ Green (Thunder Bay’s Deputy Superintendent/Research Coordinator) decided to expand the role of ATLAS to do more than just finding shipwrecks. He wanted to try using it to identify bottom characteristics, locate marine habitats, and survey prehistoric archeological sites.

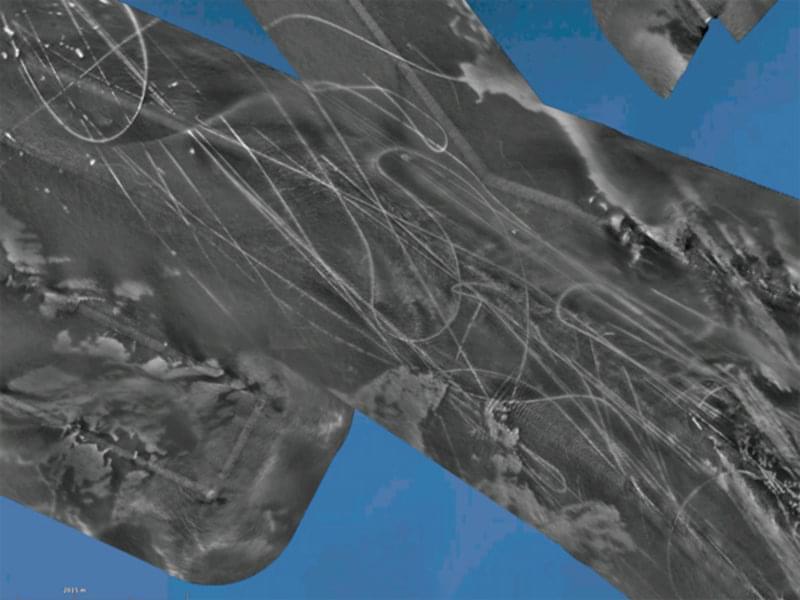

Numerous man-made “tracks” found in the northern half of Thunder Bay appear similar to anchor drags, but they are often 17 m (56 ft) wide. Some are raised a few meters above the lake bottom. Image courtesy of Thunder Bay 2010 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 50 KB).

During the Thunder Bay 2010 expedition, the team of NOAA and ARL:UT scientists had 10-and-1/2 days to run surveys. Due to the weather, missions were run on 7 days for a total of 52-and-1/2 mission hours in shallow- and deep-water areas. We surveyed approximately 104 sq mi for an average rate of 2 sq mi per hour (sq mi/hr). In deep areas, the rate increased to 3 sq mi/hr. While in the shallow areas, where the SVP limited the sonar’s operating range, the rate was 0.4 sq mi/hr (which is still higher that many other survey methods).

Numerous man-made “tracks” found in the northern half of Thunder Bay appear similar to anchor drags, but they are often 17 m (56 ft) wide. Some are raised a few meters above the lake bottom. Image courtesy of Thunder Bay 2010 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 55 KB).

The whole team was pleased with the area covered, the discoveries, and the quality of the maps. We’ve all realized that there are many applications for this sensor and/or AUV technology, including large surveys of shipwreck sites, bottom characterizations, archeological sites, and for environmental evaluation.

Ultimately, it was truly a successful test. The AUV, sonar, and processing ran without any incidents. (There were no software crashes, and no AUV crashes into the lake floor or the shipwrecks). The weather was unusually poor, and we did not get out to the deep-water area as much as we would have liked, but we still covered a lot of area.

Increasingly bad weather and dangerous seas forced a mission abort. For safety considerations, the autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) was reprogrammed swim back into to the protected waters of Thunder Bay. Image courtesy of Thunder Bay 2010 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 35 KB).

The deep-water area is difficult for NOAA to survey at this time, but even with our limited on-site time, we did survey a larger area than they had ever covered before. In the shallow area, we surveyed nearly half of Thunder Bay and the ATLAS maps revealed unexpected features and human activities

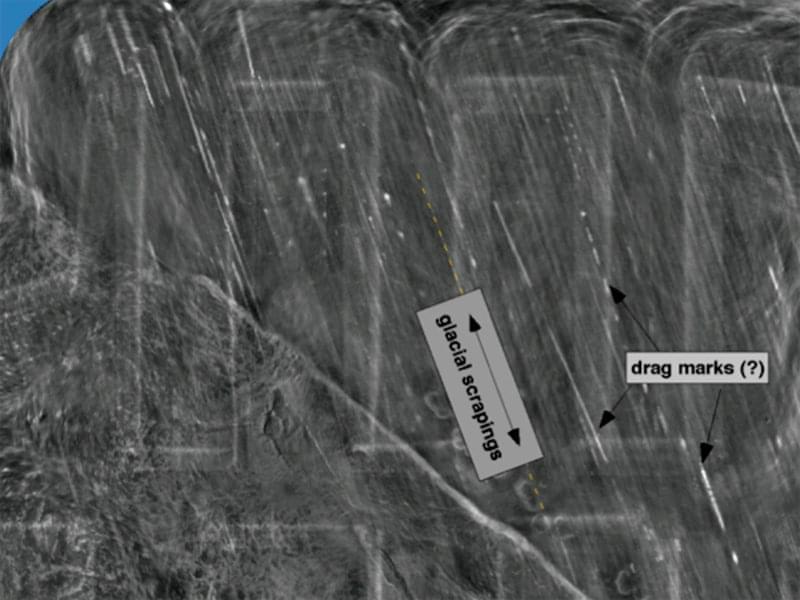

These discoveries have renewed NOAA’s interest in the region within the bay. For example, there are hundreds of 15-m (49-ft) diameter circular piles throughout the bay. A dive-team inspected one of them during our second week and discovered that they contain piles of large hunks of coal. There are also numerous manmade features that look like snowmobile tracks in the approach area to Alpena. Some are raised a few meters and some are depressed. All are roughly 17 m (56-ft) wide. There is quite a bit of speculation on their origins. In the deep-water areas, one of the dominant visible features are possibly glacial scrapings, which looked like “brush strokes” on the maps.

In addition to the amount of area surveyed, there were a number of other results from the test.

The Alpena Marina is within a few minutes of the NOAA facility. A very simple and effective technique to transport the AUV to the marina and launch it was to use a standard boat trailer. The procedure was straight forward, with no high crane lifts or jarring motions. After launch, the AUV’s remote control was used to motor it over to the support ship where it was lifted onboard with the ship’s crane. Image courtesy of Thunder Bay 2010 Expedition, NOAA-OER. Download image (jpg, 60 KB).

All of these results will help us develop or define a more robust AUV system to run increasingly independent missions, and will help us determine better ways to use AUVs to survey for objects, like those in the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary.

One “result” that was personally satisfying for the ARL:UT scientists was the ease at which the ATLAS maps were understood and interpreted by the NOAA staff and other non-engineering visitors. Everyone who came into the mapping work area would study the maps for just a couple of minutes to get oriented, then ask a few questions and begin talking about the geology of the seafloor and not about anomalies due to the sonar or processing. This group included maritime historians, archeologists, SLS operators, and divers. Everyone seemed to understand the data.