By Russ Green - Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary currently manages 48 known shipwreck sites. Should sanctuary boundary expansion occur (an increase from 448 square miles to 4,085 sq. miles), the sanctuary would have management responsibility for 83 known shipwrecks sites and the potential to discover up to 100 new sites (based on the historical record). These shipwreck sites occur in a wide range of locations/environments (i.e., near shore vs. offshore), depths (from 0 to 230-plus feet), and complexity/types (i.e., intact vs. scattered; large site vs. small; wood vs. steel). All of these maritime heritage resources possess historical significance, particularly when they are considered as a collection, and each possesses an individual degree of unique archeological potential.

Equally important, each shipwreck site is an exciting recreational venue. Shipwrecks in Thunder Bay’s shallow waters are perfect for snorkeling or kayaking, while increasingly deeper wreck sites can accommodate the full range of scuba diving abilities — from beginning divers to highly trained mixed-gas divers.

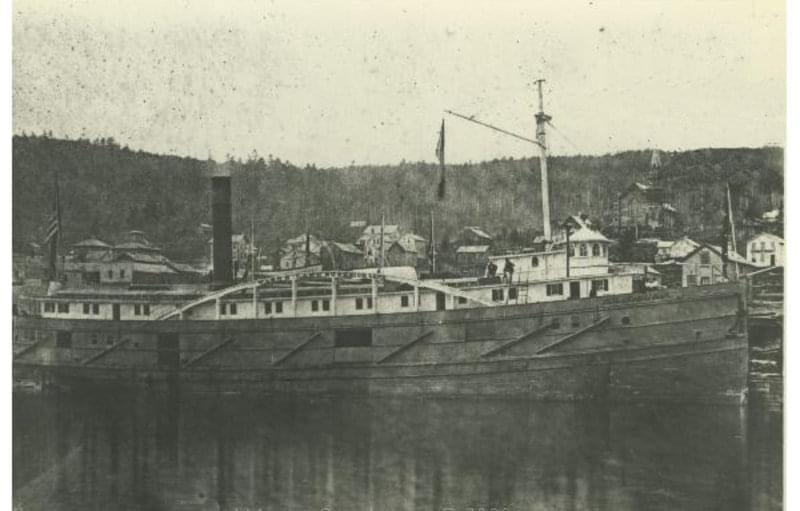

The steamer R. G. Coburn, lost in an October 1871 gale, took with her as many as 32 passengers and crew. Image courtesy of Thunder Bay Sanctuary Research Collection. Download image (jpg, 42 KB).

The first step in managing, interpreting, and preserving these sites is to figure out where they are — or where they might be. An important first stop on an archeological investigation — or the hunt for a lost shipwreck — is the archival record. Historic accounts in newspapers, lifesaving and ship’s logs, and a range of official documents often provide the initial clue to where a shipwreck might be located. The Thunder Bay 2010 project began with an archival search at the Thunder Bay Sanctuary Research Collection , which is jointly managed by the sanctuary and the Alpena Public Library. Here researchers dug up tantalizing bits of information (such as which ships may have wrecked in the area) that help inform the on-water search. This is an important part of the project’s research design.

Equally important to the project’s shipwreck component, is the idea of keeping the search area confined to an area within the historic shipping lanes. On the Great Lakes during the 1800s, the final weeks of the shipping season saw the highest profits and greatest risks. Cargo prices — and profits — climbed with the approach of winter. As October turned to November, high winds, cold, and ice often made for dangerous voyages.

Along a treacherous stretch of Lake Huron abreast of the northeast Michigan shoreline, the danger was compounded by rocky shoals, fog, and intense vessel traffic. Here, from Rogers City to Harrisville, Lake Huron’s “upbound” and “downbound” sailing routes converged. Ships passed terrifyingly close to each other as they tried to shave valuable time of their voyages. Collisions due to human error or weather are a big part of the Thunder Bay story. Surveying the waters of the historic shipping lanes may reveal shipwrecks not mentioned in the archival record.

The popular passenger steamer Thousand Islander, lost under tow in 1928. Image courtesy of Thunder Bay Sanctuary Research Collection. Download image (jpg, 37 KB).

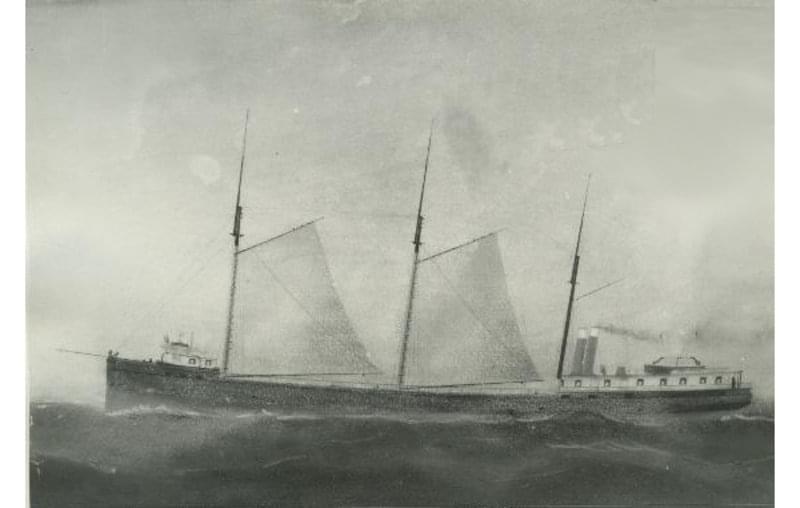

The early bulk freighter Egyptian. This vessel was one of the earliest predecessors of the 1,000-foot-long freighters plying the Great Lakes today. Image courtesy of Thunder Bay Sanctuary Research Collection. Download image (jpg, 27 KB).

Known Shipwrecks

There are several shipwrecks that researchers will be keeping an eye out for.

Steamer R. G. Coburn

Built in 1870, the 193-foot (ft) steamer R. G. Coburn (figure 1) foundered in a gale north of Saginaw Bay on October 15, 1871. As many as 32 passengers and crew lost their lives in the tragedy. All of the ship’s officers were drowned, save for the second mate, who later revealed that the vessel’s rudder broke free. For two horrific hours before dawn, the vessel lay at the storm’s mercy, while an increasing sense of panic spread throughout the passengers.

As the Coburn slipped below the cold Lake Huron waters, two of her three lifeboats drifted off unused, adding significantly to the loss of life. The Coburn was reportedly carrying 12,000 bushels of wheat, 2,900 barrels of flour, and — most significantly — silver ore. The quantity of silver ore is unknown. The wreck has not yet been located.

Steamer Thousand Islander

The 163-ft steel passenger excursion vessel Thousand Islander (figure 2) was built in 1912 in Toledo, Ohio. The popular vessel operated for seven years between Detroit, Toledo, and Chatham, Ontario. In tow of the steamer Collingwood, it sprang a leak and sank on in a storm on November 21, 1928. The wreck has not yet been located.

Freighter Egyptian

Built in 1873, the 232-ft wooden propeller Egyptian (figure 3) was lost 15 miles out of Alpena, Michigan, when it caught fire and sank off Black River in 1897. The vessel was a prototype bulk cargo carrier — a very early predecessor of the 1,000-ft bulk freighter now plying the Great Lakes. Equipped with the first fore-and-aft compound steam engine used on the Lakes, Egyptian is a highly significant historic and archeological site. The wreck has not yet been located.

Steamer W. C. Franz

The 346-ft, 3,748-ton steel bulk freighter W. C. Franz (figure 4) was sunk following collision with the freighter Edward E. Loomis on November 21, 1934, 30 miles southeast of Thunder Bay Island. Four crewmen were lost in the disaster. Radio transmission transcripts recount the disaster’s final moments as the life boats were deployed. Great Lakes shipwreck hunter David Trotter located the wreck several years ago. Although the coordinates are known, the sanctuary has limited field data on this shipwreck.

Steamer W. H. Gilbert

Built in 1892, the 328-ft steel bulk freight steamer W. H. Gilbert (figure 5) collided with the steamer Caldera on May 22, 1914. In 1983, divers discovered the largely intact wreck in 230 ft of water. Although the coordinates are known, the sanctuary has little field data on this shipwreck.